China promotes its dominant party model in Africa through a suite of training programs for party and government officials even though this model is antithetical to Africans’ preference for multiparty democracy.

A ubiquitous Chinese government talking point is the principle of non-interference in other countries. This includes issues of governance where China has long claimed that it does not export its model or encourage foreign nations to emulate its practices.

Yet, this is rapidly changing in China’s engagements in Africa. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has escalated its training of African party and government officials as part of CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping’s “new model of party-to-party relations,” particularly in the Global South. An indication of this renewed emphasis is the Mwalimu Julius Nyerere Leadership School. Launched in 2022, the Nyerere School trains ruling party members from the Former Liberation Movements of Southern Africa (FLMSA) coalition—Angola, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe.

China has built or supported African party schools going back to the 1960s. However, the Nyerere School is the first to be modeled after the CCP Central Party School, which trains China’s top cadres and leaders. It is also the first of its kind to cater to multiple African political parties. This school parallels the China-Africa Institute, a continental CCP initiative to train African party and government leaders. The Institute, which started in 2019, is based within the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in Beijing and the African Union (AU) in Addis Ababa.

CCP-supported governance and party training also occurs at the national level as illustrated by the refurbishment of the Herbert Chitepo School of Ideology, the ruling Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF) party school, completed in 2023.

China’s party and governance training has the potential to entrench single, dominant party models in Africa.Less noticeable are the non-brick-and-mortar schools of China’s National Academy of Governance (CAG), the external name for the CCP’s Central Party School. Algeria, Ethiopia, Kenya, and South Africa are among the African countries whose governance academies maintain year-round training partnerships with CAG. China’s party exchanges have increased alongside this expanding training. China is expected to receive over 50 African party delegations this year—double the number of party visits hosted in 2015.

While often overlooked in discussions of party training, Chinese government institutions also run programs in Africa (and the Global South more generally) on “sharing governance experience in governing state affairs” (fen xiang zhiguo li zheng jin yang; 分享治国理政经验) that mirror the CCP initiatives. Many of these trainings place emphasis on party supremacy over the state and government, a concept that is at odds with the multiparty democratic framework required by most African constitutions and AU conventions. Notably, CCP party schools are embedded in the structure of China’s government institutes.

China’s constitution describes the government as a “people’s democratic dictatorship.” This oxymoronic framing is an anchor concept that runs through the CCP’s entire suite of political trainings. It is popular with African ruling parties intent on extending their longevity. According to the head of one African government training school, “They [CCP] show us what they achieved without the messiness of democracy.”

Despite its economic growth, China’s political model has not been something to which many African citizens aspire. Nearly 80 percent reject one-party rule. Yet, as many African scholars argue, China’s party and governance training has the potential to entrench single, dominant party models in Africa. The CCP’s foreign training programs are also heavily oriented towards elite capture. National elites, in turn, are keen to use their ties to China to entrench their rule. This escalation in CCP party training is happening against the backdrop of major democratic setbacks in Africa in recent years.

Advancing China’s Dominant Party Model in Africa

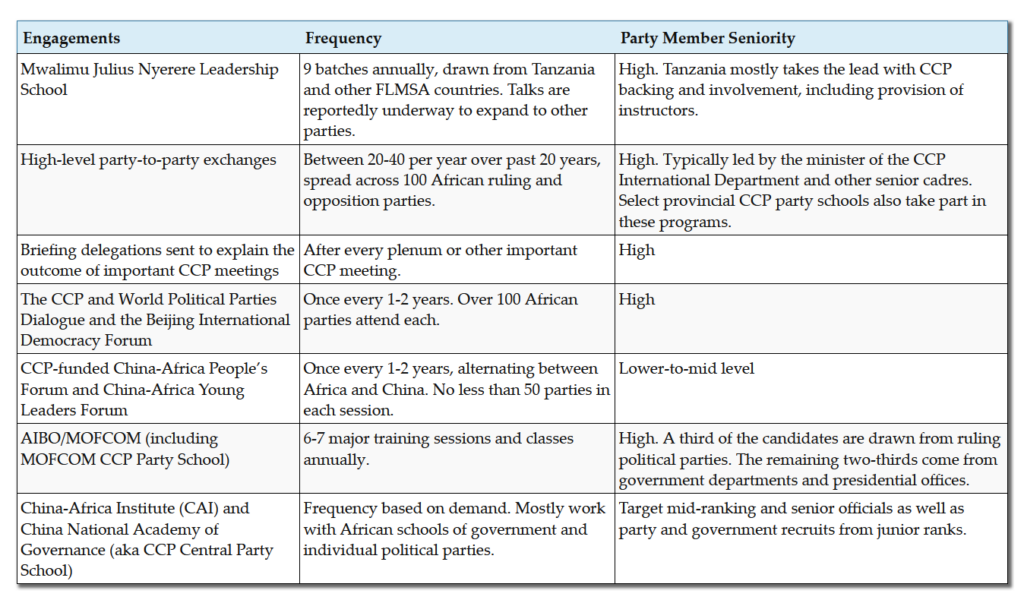

The blurred line between the CCP and the Chinese state mirrors the situation in parts of Africa where the interests of the ruling party are self-interestedly conflated with those of the state. China has many venues to advance its governance philosophy and practice. Between 2000 and 2022, the CCP carried out 881 exchanges (807 bilateral and 74 multilateral) with African ruling and opposition parties, according to the CCP International Department’s metadata.

The CCP has ongoing relations with 110 African ruling and opposition parties, 35 parliaments, and 59 politically oriented organizations, including party think tanks. In 2017, Xi Jinping directed the CCP to conduct 15,000 exchanges globally over the next 5 years, driving it to tap into its vast network of over 3,000 political schools, some of which have subsequently established their own training programs in Africa. CCP training also occurs via state agencies like the Academy for International Business Officials (AIBO) in the Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM). AIBO is China’s flagship foreign training institute, which works closely with the MOFCOM CCP Central Party School.

Participants in the AIBO training system must be citizens of developing countries. Scholarships for graduate studies in government are given to candidates under 45 years of age, highlighting China’s interest in shaping younger generations of party and government leaders. Nearly all 21,123 AIBO government and ruling party trainees between 2021 and 2022 were from developing countries, with about a third from Africa.

There has been strong demand for CCP engagement from some African ruling parties. The decision to establish the Nyerere School was taken at the 2016 FLMSA Heads of State Summit. Tanzania, which was chosen as the venue, played a major role in securing the CCP’s support. The Chitepo School was revived in 2016, having been disbanded at Zimbabwe’s independence in 1980, with construction beginning in 2021. China’s stepped-up support for the local party schools of the six FLMSA countries was also undertaken on the initiative of the parties concerned.

Xi’s directive to expand party training, in short, has been advanced in four ways in Africa:

The resumption of party school construction

“Brainstorming summits” for party leaders, like the CCP and World Political Parties Summit and the Beijing International Forum for Democracy

CCP briefing delegations

Support for African governance academiesThe “brainstorming summits” assemble 300-500 political party leaders globally every 1-2 years—a venue for China to win support for its governance concepts among foreign political parties. The CCP and World Political Parties Summit sponsors an Africa Thematic Event that Tanzania hosted when the gathering first met in 2018. The CCP briefing delegations consist of top CCP leaders sent to brief their foreign equivalents about the outcomes of major CCP meetings. These include the CCP’s annual plenum, which maps out China’s overall strategic direction.

What Exactly is China’s Governance Model?

China’s governance system has four dominant features: party supremacy, fragmented authoritarianism, political meritocracy, and party-led economic governance.

Party supremacy is the most attractive feature for many ruling parties in Africa. A major study of 71 African political parties found that “The [African] party in power is hardly autonomous from government influence and it is difficult to draw the line between where the influence of government begins and that of political party ends.”

China’s model of fragmented authoritarianism gives significant autonomy to lower state structures as long as they do not deviate from party control. Hence the regime can rally around a “strong leader,” dispense patronage, and prevent alternative power centers from forming, a disposition many patronage-laden African systems share with China.

China likes to call itself a “political meritocracy,” that favors effective, technocratic government and claims legitimacy by equating democracy and human rights with economic development. This explains why the Chinese concept of democracy is married to China’s economic achievements. African leaders make similar arguments. As Rwanda’s President Paul Kagame explains, “There is nothing like human rights minus … development. These are human rights: development, schools, education, health, and food security.” Left unstated in this argument is that autocratic governance has been a major source of instability in Africa. Many top African development thinkers, moreover, note that economic development without democracy is ultimately unsustainable as it exacerbates societal cleavages, institutionalizes corruption and party privilege, and ignores the social roots of conflict.

China’s rekindled interest in African party schools is also something of a marketing endeavor. After the Nyerere and Chitepo schools opened, many approached the CCP to build their schools and enhance their party building, including Burundi, the Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Morocco, and Uganda.

Even Kenya’s United Democratic Alliance (UDA) has requested the CCP to build its new party headquarters, leadership school, and Kenya’s new foreign ministry building. China seems to be following the model it used in Ghana where, since 2018, it has provided successive Ghanaian ruling parties political leadership training. The dalliance of Kenyan and Ghanaian parties with the CCP offer a glimpse into how China seeks to engage and reshape governance norms even in more pluralistic and open contexts.

The CCP prizes regular contact, replication, and critical mass. Three parties, Tanzania’s Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM), South Africa’s African National Congress (ANC), and Zimbabwe’s ZANU-PF collectively trained over 900 cadres in China between 2000 and 2022. Over the same period, China conducted exchanges, party building, and training with every African ruling party apart from Eswatini’s. The China-Africa Institute has trained 348 party and state officials through the Ethiopian, Kenyan, and South African governance academies alone.

The China National Academy of Government (CCP Central Party School) has trained 400 Algerian ruling party and government officials since 2015 and run similar programs for Egypt, Tunisia, and South Africa. As leading China scholar, Yun Sun, explains, the CCP’s party-to-party work is “geographically expansive, institutionally systematic, and psychologically and politically impactful over the choices and preferences of African political parties and, thus, over the African political landscape.”

CCP Training Packages for African Political Parties

Implications for African Citizen Agency

Africa’s pro-democracy voices and civil society leaders consider the CCP’s enhanced party engagements as directly hostile to Africa’s democratic project. Many of the CCP’s partners share anti-democratic features like highly personalized political institutions and little to no accountability, even though China’s economic programs remain popular. China is therefore viewed as a negative actor for Africans’ democratic aspirations. It should be recalled that Africa’s experience with single-party rule was almost uniformly negative, explaining the popular groundswell of pro-democracy movements that spearheaded the collapse of one-party states during the 1990’s transition to multiparty politics.

Africa’s experience with single-party rule was almost uniformly negative.Those who question African ruling parties’ embrace of China’s party training are often dismissed as “Western puppets.” Africa’s democracy proponents strongly push back on this characterization, however. “It is Africans themselves who long for democracy,” says scholar Tafi Mhaka. This is supported by polling. Afrobarometer finds that nearly 70 percent of Africans surveyed prefer democracy to any other type of government. Roughly 80 percent reject one-party rule. China’s dominant single-party system, therefore, runs diametrically counter to African citizen interests.

A growing number of voices also take issue with Africa’s assumed position as a “perennial student” of foreign powers. Africa possesses a wealth of noteworthy experience that it can teach others such as negotiating political disputes, reaching out to former enemies, and upholding democratic processes even if it means losing power as many African parties have done. Rather than a weakness, such features are healthy attributes of democratic self-correction and accountability—guarding against corruption and abuses of power.

For Africa’s democracy advocates, such attributes are worth defending and vital to Africa achieving both the freedoms and prosperity that its citizens desire. This, too, is supported by experience. Africa’s authoritarian governments are linked to three-fourths of the continent’s conflicts, 80 percent of its forcibly displaced populations, and 85 percent of the acute food insecurity in Africa. Africa’s consolidating democracies, meanwhile, typically generate two-thirds more rapid economic growth, realize higher educational attainment levels, have lower infant and child mortality rates, and longer life expectancies.

Disconnect between Ruling Parties and Citizen Interests

There is a disconnect between the trajectory certain African ruling parties would like to follow and the democratic path desired by citizens and enshrined in constitutions. While some African ruling parties may try to dress this up, their enthusiasm to train with the CCP is essentially about (re)normalizing dominant single-party systems. These forces are on the ascendant as the CCP sees ramped-up party training as a key lever of influence and some ruling parties see it as a means of justifying their hold on power indefinitely.

Additional Resources

Niva Yau, “A Global South with Chinese Characteristics,” Report, Atlantic Council, June 13, 2024.

Paul Nantulya and Leland Lazarus, “Lessons from China’s Forum Diplomacy in Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, January 22, 2024.

Joshua Eisenman, “China’s Relational Power in Africa: Beijing’s ‘New Type of Party-to-Party Relations,” Third World Quarterly 24, no. 12 (2023).

Paul Nantulya, “China’s First Political School in Africa,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, November 7, 2023.

Paul Nantulya, “China’s Deepening Ties to Africa in Xi Jinping’s Third Term,” Spotlight, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, November 29, 2022.

Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Autocracy and Instability in Africa,” Infographic, March 9, 2021.

Lina Benabdallah, “Ties that Bind: China’s Party-to-Party Diplomacy in Africa,” Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, October 2021.

Niel Thomas, “Proselytizing Power: The Party Wants the World to Learn from Its Experiences,” Macro Polo, January 22, 2020.

Morton H. Halperin, Joseph T. Siegle, and Michael M. Weinstein, The Democracy Advantage: How Democracies Promote Prosperity and Peace, revised edition, (New York: Routledge, 2009).

Yun Sun, “Political Party Training: China’s Ideological Push in Africa?” Brookings, July 5, 2006.