The conflict is a complex multi-sided one wherein the West, religious extremists, and Algeria have shared interests in the Malian government meaningfully decentralizing power to Tuareg-inhabited areas (each in pursuit of different ends), while Bamako and Moscow support a centralized state.

This weekend’s reportedly devastating ambush of rebranded Wagner in Northern Mali by Tuareg separatists brought this ethno-national conflict to the forefront of Russia’s attention. Moscow dispatched PMCs to Mali as part of its “Democratic Security” efforts to help the central government protect its national model of democracy from Hybrid War threats, including those that are externally exacerbated. The conflict was hitherto simplified as a Western-Russian proxy war in the New Cold War.

The latest development might prompt a fundamental rethinking of its origins and solution, however, since it should become clear to policymakers that everything is much more complicated than they thought. Mali is the core of the newly formed Sahelian Alliance/Confederation with neighboring Burkina Faso and Niger, which is considered the catalyst of regional multipolar processes. Russia has geostrategic interests in helping its members fight against separatist (Tuareg) and terrorist (radical religious) threats.

The problem though is that these two risk once again converging just like they did shortly after NATO’s War on Libya, which resulted in a large-scale but ultimately failed French intervention from 2013-2022. The trigger for the latest round of this decades-long on-and-off conflict is the central government scrapping the 2015 Algiers Agreement for partial Tuareg autonomy in early January that was mediated by this traditionally nomadic group’s Algerian partner.

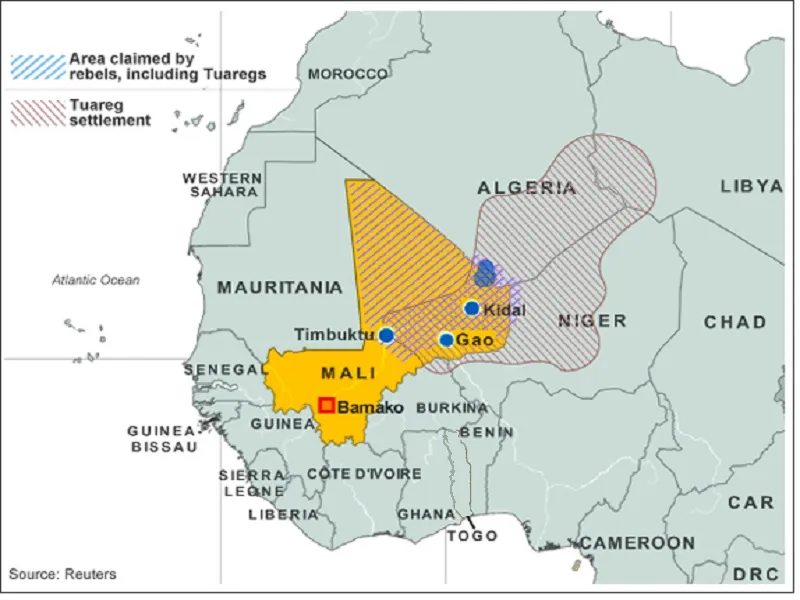

The lead-up to that decision was Russian PMCs helping Malian forces retake the Tuaregs’ regional stronghold of Kidal late last year, which caused panic in the separatists’ ranks and led to them holding meetings with Algeria that Bamako considered to be an unacceptable intervention in its domestic affairs. Prior to that, Russia suspected that the separatists were once again cavorting with religious extremists and colluding with the West, and new evidence has emerged suggesting that Kiev might be involved too.

Absent from these perceptions was the role that Algeria might be playing in providing some level of aid to its Tuareg partners, which it considers to be a means for maintaining influence in Mali and controlling the situation there so that it doesn’t lead to separatism spilling over into its own borders. Algeria is also a close Russian partner just like Mali is, but Algiers’ interests diverge from Moscow’s and Bamako’s in this case, though that’s not to imply that it’s colluding with the West/Kiev or religious extremists.

Rather, the conflict is a complex multi-sided one wherein the West, religious extremists, and Algeria have shared interests in the Malian government meaningfully decentralizing power to Tuareg-inhabited areas (each in pursuit of different ends), while Bamako and Moscow support a centralized state. The following four news items shed more light on the Algerian-Malian security dilemma that’s recently re-emerged throughout the course of the latest Tuareg Conflict:

- 22 December 2023: “Tensions between Algeria and Mali, ambassadors summoned”

- 27 January 2024: “Algeria Expresses Concerns After Mali Suspends ‘Reconciliation Agreement’”

- 12 February 2024: “Algeria-Mali tensions: Long storm to instability in African Sahel”

- 2 July 2024: “Russia will have to choose between Algeria and Mali”

As can be seen from the last one, Russia is now being thrown into its own dilemma over whether to support Algeria’s desired decentralization of Mali by attempting to revive the political process in that direction or Mali’s desired centralization by doubling down on its PMC-driven military support for Bamako. The first risks creating distrust within the newly formed Sahelian Alliance/Confederation while the second risks Algeria working together with the West on this issue if Russia goes against its interests.

Algeria’s military is dependent on Russian supplies, and relations with the West are complicated, but Moscow might not curtail its arms exports to Algiers as revenge since that could scare its other partners away while the West might use any cooperation as the basis for resetting their ties. Similarly, the Sahelian Alliance/Confederation is in a similar boat (albeit transiting from French arms to Russian ones), and its Malian core could swap Russian PMCs out for Turkish ones if Moscow pushes for peace talks.

Decentralizing parts of Northern Mali by giving the Tuaregs at least their previously promised partial autonomy is seen by Algiers as the most effective way of managing this decades-long conflict and preventing its recurrences that always risk spiraling out of control and spilling over into its borders. Likewise, restoring the centralized state’s writ over the north is seen by revolutionary Bamako as the only way of preventing the West from destabilizing its new government by proxy, which Moscow agrees with.

Each side has legitimate but contradictory interests, and the trust deficit impedes any compromise. Neither wants to return to political dialogue since they’re convinced that they can gain more, including maximum victory, by continuing to fight. The origins and socio-political dynamics of the Tuareg Conflict closely resemble the Iraqi and Syrian Kurdish Conflicts, however, to which there isn’t a military solution. Iraq granted them autonomy long ago while Syria might soon have no choice but to follow suit.

Each of these separatist conflicts is driven by their ethno-national group’s perceived status as second-class citizens in the respective states that they inhabit, and forcible centralization has always led to another round of rebellion, even if it takes time to manifest. Furthermore, the resultant separatist-state friction creates openings for third parties like the West and religious extremists to exploit, which wouldn’t have otherwise been available had these conflicts been resolved long ago.

This cycle contributes to perennial instability that’s then taken advantage of by state (the West) and non-state (religious extremists) actors for divide-and-rule purposes. Neither the Syrian Kurds nor the Tuaregs are going to have their hearts and minds won over by the states in which they inhabit without some form of constitutionally guaranteed autonomy. Accordingly, Russia would do well to think about how it could pair military and political means for resolving this conflict, or it risks getting caught in a quagmire.