A rare trip by Post journalists to five Sudanese cities revealed starvation, mass displacement — and acts of stunning heroism.

Every day, fighting between the military and a powerful paramilitary group confronts Sudanese with agonizing choices.

A father must decide whether to leave his other children behind and try to rescue a son trapped behind the front lines of Sudan’s devastating civil war.

A doctor must choose whether to run home to rescue his parents, who had come under bombardment, or stay with the hospitalized children whose lives depend on him.

An impoverished young man must weigh a militia recruiter’s promise of riches against the prospect of death in battle.Restrictions on reporting have largely obscured the catastrophic toll of Sudan’s war, abetting international neglect. But a rare reporting trip inside the country provided glimpses of fear, despair and remarkable heroism.

Now in its 15th month, the war is getting worse. The Rapid Support Forces paramilitary is advancing, capturing more territory and displacing millions of Sudanese, in turn fueling the world’s largest hunger crisis. Famine looms. About 750,000 people are on the brink of starving to death, the United Nations says. The United States estimates the war has already killed 150,000 people.

Foreign countries are taking up sides, fueling the conflict, and assorted militias and mercenaries are joining the fray. The conflict in Africa’s third-largest country is spilling across the borders and destabilizing its neighbors. U.S.-backed peace talks have stalled.

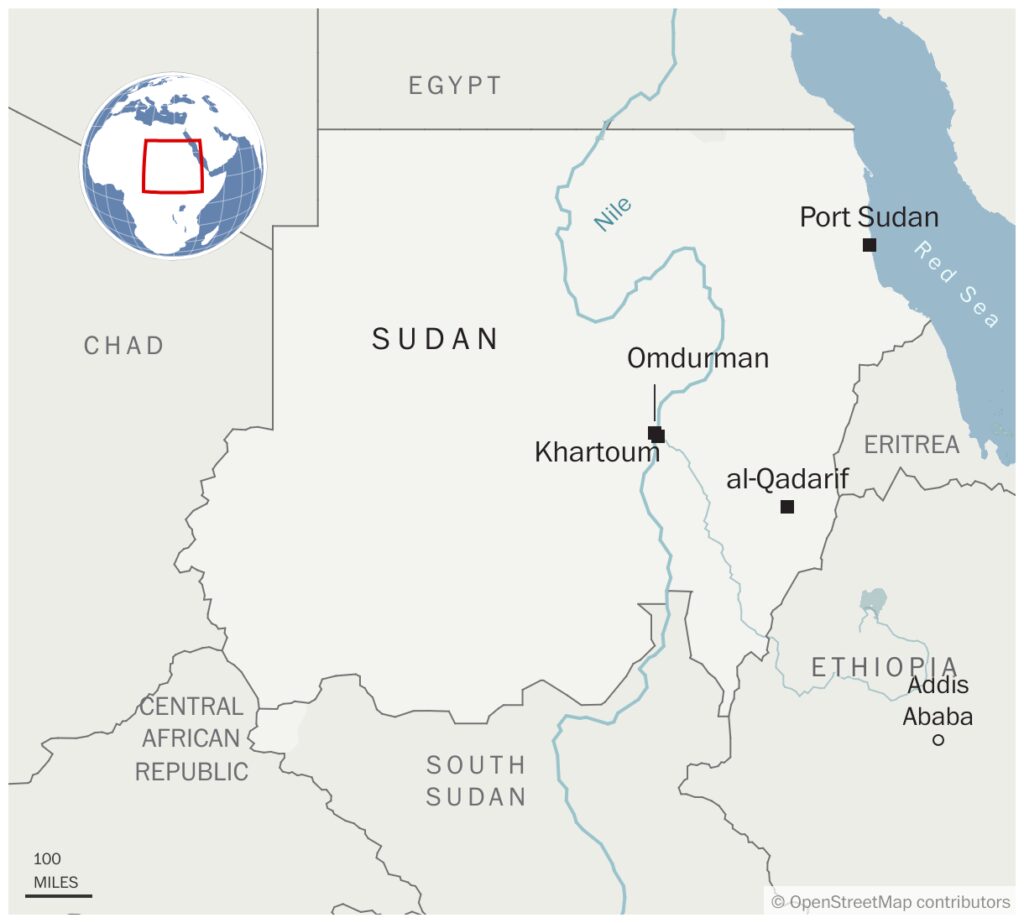

The war pits the RSF against the armed forces. Their respective generals — RSF chief Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, universally referred to as Hemedti, and the military’s Abdel Fattah al-Burhan — had jointly seized power from a civilian-led government then turned on each other in April 2023, sparking the civil war. The RSF has seized almost all of the gold-rich western region of Darfur and stormed into the agricultural heartlands of the south. The military holds the arid north and the fertile east along the banks of the Nile River.

The military’s only major offensive has clawed back most of Omdurman, the country’s second-largest city located across the Nile River from the capital Khartoum. Life has returned to some neighborhoods, although shells still crash down, but those closer to the front line remain largely abandoned. Barricades of earth and household furniture erected by vanished residents block off streets.

The headquarters of the Sudan Broadcasting Corp. is a blackened shell after a month-long battle there. Some of its offices were converted to makeshift prison cells. Knotted restraints used to tie up prisoners hang from the window bars; soldiers say it had been used as a torture center.

A team of Washington Post journalists visited five Sudanese cities last month in areas controlled by the armed forces, interviewing dozens of people and chronicling their lives. Most of the interviews were conducted in the presence of military or intelligence officials, and some people were inhibited in what they would discuss.

In the emergency wards, the hennaed hands of mothers fanned the twig-like ribcages of babies struggling for breath, and other parents told of sleeping children killed in their beds when artillery shells crashed into their neighborhoods. Prisoners and soldiers alike spoke of young men shot far from home, their corpses decaying in the heat, before they were flung in unmarked graves.

“We’re still finding bodies inside these,” said a soldier, motioning to the blackened shop fronts of a former gold market, their brick walls collapsing into ruin. Shards of broken glass and cartridge shells crunched under his feet, along with the debris of lost lives: broken tea cups, a baby’s bottle.

Here are stories of struggle amid the converging crises of health, hunger, violence and displacement, of the deceptive allure of war and the stubborn dream of peace.

The doctor

Ghassan Ahmed had recently finished his medical internship when gunfire erupted in Khartoum, just across the Nile River. Social media said the violence was spreading fast. He rushed to al-Buluk pediatric hospital in Omdurman, where three frightened female doctors were caring for 110 sick children.

“I told the women doctors to go home, and I stayed alone,” said Ahmed, 26. “It was chaos.”

Frantic families swept in to grab their children until only 30 patients were left, cases so severe they would die if they were moved, he recalled. The bombing moved closer. Ahmed barred the gates.

“Some sort of missile flew over the top of the hospital. And when night came, I got really scared. You could see [tracer] bullets flying in the air,” he said. “Our house is really close to an RSF camp, and my mom called me crying to say goodbye because she thought they were going to die.”

He spent the night reassuring crying children and their mothers. The next day he reluctantly handed off responsibilities to his friend Abdallah, and went home through eerily deserted streets dotted with corpses to check on his family. His mother begged him to stay, but the children needed him.

For the next two weeks, he, Abdallah and a nurse were the hospital’s only medical staff. They slept when they could — but emergencies seemed to occur every hour. When a 6-year-old girl died, he and a few parents helped the mother dig the grave. And when antiaircraft fire slammed into a plane overhead, he recounted, two of them dove into the grave for cover.

Another time, more than a dozen explosions rocked the hospital. “The mothers got under the beds with their children, so I had to crawl under there to give them medicine,” he said.

So far, the hospital has been mostly spared. A nurse’s brother was injured in a bombing. A couple of weeks ago, a stray bullet hit a doctor in the pelvis in the courtyard. But unlike many other hospitals, the wards have not been hit by a shell.

The hospital, supported by the Sudanese American Physicians Association, is back up to 80 percent of its prewar capacity, Ahmed said. About a third of its patients are extremely malnourished, but aid has arrived and mortality has improved: a couple of babies die each week instead of one every day.

Ahmed moves down the rows of beds, touching tiny limbs. He exudes calm; inside he’s seething. Sudan has its worst levels of hunger since records began.

“If you discharge a patient today,” he said with frustration, “they will go home to starve.”

The prisoner

Six bullets slammed into Luol Ajou before he fell to the street, he recalled, pulling up his shirt and trousers to reveal the scars, guiding a reporter’s fingers to a sharp fragment in his upper arm. “That one is still inside.”

Ajou was among five prisoners, ages 16 to 20, who said they were previously members of the RSF before being captured during the battle for the Sudan Broadcasting Corp. in Omdurman. Now, they were prisoners of the military and had been brought from their detention center to be interviewed. Outside, the crackle and boom of combat in Khartoum echoed across the Nile.

One 16-year-old said he originally came from neighboring Chad and was working as a security guard in Libya when he was recruited with around 300 others. Another 16-year-old was recruited by a tribal leader in Chad. The young men slipped across the border individually before mustering with the RSF in Darfur and being taken to Khartoum in trucks, he said. (An RSF spokesman did not respond to a request for comment.)

Sudan’s civil war is sucking in waves of young men from around the increasingly unstable region. Coups and corruption often mean they have no jobs and little education — except how to use a gun.

Ajou, 20, was recruited from his native South Sudan when he was a teenager. He had completed four years of school before his older brother Deng, a soldier, taught him to maintain and use heavy weapons like antiaircraft guns, rocket-propelled grenades and mortars.

By age 15, Ajou said he was getting the equivalent of nearly $100 a month from the South Sudan army, a decent salary that helped his parents feed their family of 10. But as he neared 18, Deng warned him to leave the army or risk being sent into combat. Ajou worked odd jobs, until a cross-border trader told him last year that the RSF would pay $100,000 for a weapons specialist. It seemed like his big chance.

He never got the cash.

Echoing the stories of other recruits, Ajou described being taken to a building in Khartoum, where RSF commanders selected small groups of fighters for their units. He was sent to defend the Sudan Broadcasting building and promised his cash later. A terrifying month under heavy bombardment followed, he recounted. The military encircled them.

One night, their commander ordered a small group to break through the lines. They tried. Most were killed. The handful interviewed by The Post were captured.

Ajou said that as he had bled into unconsciousness, he’d thought about his big brother, Deng.

“He told me to stay away from war,” Ajou said ruefully. “I should have listened.”

The father

The last time Hassan saw his middle son, 10-year-old Mokhlis, the boy had playfully asked his father for new clothes for the Muslim festival of Eid al-Fitr. Hassan, 48, a powerfully built construction worker, promised to find the money. They hugged before Mokhlis returned to his aunt’s house, where he often stayed because of its proximity to his school. They expected to reunite within a couple days, Hassan recounted during an interview at a dusty camp in the eastern town of al-Qadarif, where he is now one of about 11 million Sudanese displaced from their homes.

When the war came, it sliced Khartoum into enclaves. The front line snaked past Hassan’s house, and Mokhlis couldn’t come home. His parents reassured him every few days by phone that the violence wouldn’t last.

Weeks stretched into months. Hassan said he had wanted to retrieve Mokhlis but worried about leaving the rest of the family behind. It had also become too dangerous for men to exit their homes. Fighters often arrested, tortured or killed men on the streets, he said. Hassan’s wife Gisma fetched the family’s food. In June, she and their 8-year-old son went out to buy provisions. They never returned.

“I found them the next day,” Hassan said softly. Their blood-soaked bodies lay on the street, tangled with six others hit by a shell.

Hassan’s 18-year-old daughter braved the risk of rape at roadblocks to find Mokhlis and inform him about their mother’s death in person. But her courage failed when she saw him. Her aunt did instead.

Hassan’s area, meantime, was growing even more perilous, he recalled. He sent his mother and three remaining children out of town, while he stayed in their home to guard it from looters. But when they came, he was powerless to stop them.

Homeless, he fled to a military-controlled area but was hit by mortar shrapnel. Soldiers dragged him to a military hospital, where doctors saved his life. A jagged scar now slices across his abdomen.

It took him two months to recover, he said. He spent another two weeks hiding out in deserted homes with almost no food or water, playing cat and mouse with the gunmen and trying to sneak through the front lines.

In the end, the RSF caught him, he said. They beat him for three days while they interrogated him but eventually released him because his weakened state disqualified him as a soldier. By then, he had lost contact with Mokhlis.

The dreamers

When the generals dissolved Sudan’s joint civilian-military government and seized power in 2021, Mahmoud Abdirahman joined thousands of other young Sudanese in protest, demanding a return to democracy.

Those protests paused after war erupted last year, but like so many in his generation, Abdirahman has channeled his idealism in a new direction by helping others affected by the conflict.

Many Resistance Committees, which had organized the protests, have been rebranded as Emergency Response Rooms. Its activists swap information about safe routes through the fighting, source scarce medicine and find shelter for the homeless.

Abdirahman, a 22-year-old economics student, now stays in the military stronghold of Port Sudan, which is swollen with displaced families. He and his friends raise money to pay the medical fees for these families and organize clothing drives and soup kitchens. There’s an uneasy truce with the authorities, although activists still get arrested sometimes.

“They think we are troublemakers, so they make trouble for us,” he said, a cheeky smile on his lean face.

Couriers smuggle medicine from Port Sudan across the front lines for needy families. It’s dangerous work. More than 40 volunteers have been arrested in Khartoum alone, he said.

A fellow volunteer in the Khartoum suburb where Abdirahman used to live was arrested carrying several packets of medicine, the volunteer later told Abdirahman. That friend said he had been taken to, of all places, Abdirahman’s former home, which like many other private homes had been seized by the RSF. It was now being used as a center for torture and executions. He was held there with more than 50 others for a week.

After his release, he sobbed as he described how prisoners were killed or died after severe beatings. He said he had been tortured with electrocution.

“We had so many happy memories of our home,” Abdirahman said, tears sliding down his face. “Now people are being killed there.”

Most volunteers have stories of loss or near misses.

A middle-aged woman with chipped nail varnish and a sparrow-brown headscarf described hiding medical equipment from the RSF to prevent it being looted. A former IT worker in freshly pressed robes said he’d driven, shaking, between the warring sides to fetch medical supplies. A young man still too scared to speak much told of another volunteer, a friend, who died at al-Nao hospital in Omdurman on June 20 when a shell slammed into the compound, killing three and injuring two dozen.

But many volunteers remain undeterred.

“I still believe democracy is coming,” Abdirahman said, a mural commemorating dead protesters on a wall behind him. “After the war, we will go back on the streets and fight the winner. And we will keep fighting until democracy wins.”