A comprehensive cessation of hostilities is necessary for the country to reap the benefits of effective transitional justice.

Last month, Ethiopia’s Ministry of Justice announced the completion of the roadmap for implementing the Transitional Justice Policy adopted in April. The roadmap is expected to outline activities that provide for criminal accountability, reparations, truth-seeking and institutional reform, and their sequencing.

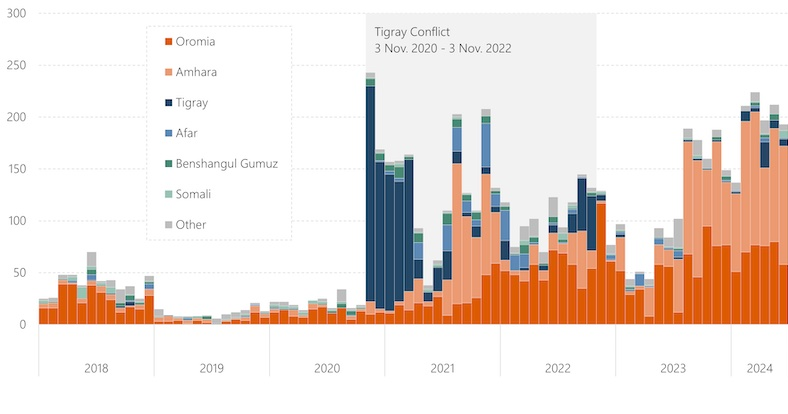

The policy was drafted after a series of consultations and surveysbetween January 2003 and April 2024 that took place amid ongoing armed conflicts. While the Tigray war ended in late 2022, battles continued in Oromia and fresh clashes broke out in Amhara (see chart). Although the official position is to implement transitional justice while hostilities are ongoing, is that possible?

In discussions and workshops on Ethiopia’s process, experts and officials have said drafting policy on transitional justice amid armed conflict is not unusual, and is indeed prudent. One could argue that delaying policy design until peace has been achieved is not always feasible. Also, according to the During Conflict Justice Dataset, 76% of countries studied since 1946 have established some form of justice during war.

Nevertheless, designing such policy amid conflict differs vastly from attempting to implement it under the same or worsening conditions. Although Ethiopia’s Working Group of Experts has cautioned on the difficulty of application in this context, the Transitional Justice Policy doesn’t highlight the need for a peace process. This contrasts with the African Union’s (AU) policy, which says peace processes should be integral to transitional justice efforts.

Peace can enable the implementation of transitional justice in many contexts. In Ethiopia, it can ensure the meaningful participation and public buy-in needed to increase the process’ compliance with international standards.

One of the primary goals of Ethiopia’s policy is to end the cycle of violence through institutional reform. However, without first ending ongoing conflicts and addressing the structural issues that led to the fighting, it might be impossible to guarantee the non-recurrence of violations. Simply reforming institutions won’t ensure a future governed by the rule of law.

Pursuing accountability during violence is not only tricky in practice but may fail to deter further atrocities

The policy also calls for special judicial, investigative and prosecutorial mechanisms to establish criminal accountability. However, pursuing accountability during violence is not only tricky in practice, but may fail to deter further atrocities. The International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia was established during the conflict. Some of the worst atrocities, including the Srebrenica genocide, occurred while it was operational.

Achieving peace can urge militants to participate in the transitional justice process. In several countries, such processes have included armed groups, former fighters and liberation movements. Ending conflict could also make Ethiopia’s currently inaccessible and ungoverned spaces available for dialogue, truth-seeking and accountability.

Peace can bring political parties to the transitional justice table. Some parties in Ethiopia walked out of sessions in 2023, citing the need to cease hostilities before discussing transitional justice. Others continued questioning the Transitional Justice Policy’s legitimacy, including during validation workshops on the draft policy. Without peace, political parties and their joint council won’t be stakeholders in the implementation process.

Furthermore, achieving peace would help change the views of civil society organisations, who are sceptical of Ethiopia’s transitional justice efforts due to the ongoing hostilities. They could engage more actively in the civic space, contributing to more comprehensive and effective implementation.

Ending conflict could make Ethiopia’s inaccessible spaces available for dialogue, truth-seeking and accountability

Peace could also facilitate the involvement of the over three million-strong Ethiopian diaspora. They haven’t participated in national consultations or surveys on transitional justice due to logistical challenges and a perception that some were war-mongering online. As victims, perpetrators, witnesses and experts, the diaspora could play a critical part in the roll-out phase.

Youth are key players in armed conflicts, non-violent protests and peacebuilding, but are often excluded from transitional justice processes. Peace could enable their voices to be heard and bring them into proceedings. Similarly, ensuring the participation of victims trapped in conflict zones and providing them with mental health and psychosocial support is vital. This would be easier to facilitate in a context of peace.

The international community, particularly the United States and European Union, has urged Ethiopia to implement transitional justice as part of its commitment under the 2022 Cessation of Hostilities Agreement, which it helped broker. External actors have also facilitated recent preliminary peace talks between Ethiopia’s government and the Oromo Liberation Army. Continuing and expanding these efforts in collaboration with regional actors such as the Intergovernmental Authority on Development and AU Commission is crucial.

Ethiopia’s government could leverage its transitional justice efforts to show a genuine commitment to peace. Armed groups in Oromia and Amhara must also engage sincerely in talks. Despite their length and potential frustrations, peace negotiations should adopt a conflict-sensitive approach that includes all parties.

Since the 1991 London peace talks between the Dergue and liberation movements from Eritrea, Oromia and Tigray, selective and largely bilateral negotiations and incomplete peace efforts have led to recurring conflicts. The post-1991 partisan and mismanaged transition led by the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) brought another era of violence and repression.

Delaying peace in Ethiopia will undermine the timely implementation and effectiveness of transitional justice

The Ethiopia-Eritrea accord, which earned Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed Ali a Nobel Peace Prize in 2019, is cited as one of the reasons for the Tigray war, as the TPLF felt marginalised and antagonised. Some say the current Amhara conflicts may have stemmed from the selective nature of the Cessation of Hostilities Agreement.

Peace processes in Ethiopia should integrate transitional justice requirements to ensure peace and justice coexist. However, talks sometimes become avenues for negotiating amnesties, creating impunity clauses that hinder transitional justice.

Rather, as exemplified in the Cessation of Hostilities Agreement and highlighted in the AU’s transitional justice policy, peace agreements should include provisions for addressing crimes through transitional justice frameworks. This can be achieved by incorporating criminal accountability, institutional reform, truth-seeking and reparations early in the negotiations.

A well-crafted peace agreement could also reduce tensions between disarmament, demobilisation and reintegration programmes and transitional justice efforts.

The need for peace in Ethiopia is paramount and urgent. Delaying it will undermine the timely implementation and effectiveness of transitional justice.