Key Takeaway: High-level Russian officials are meeting with Russian partners across Africa, seeking to advance the Kremlin’s strategic goals of projecting greater Russian influence to supplant the West and better positioning Russia for prolonged confrontation with the West. The visits are strengthening Russia’s military footprint on the continent, which enables the Kremlin to use its limited resources to threaten NATO’s southern flank and degrade Western influence, advancing the narrative that Russia is a revitalized great power on par with the West. Russia is also attempting to strengthen economic engagement with Africa in various sectors to alleviate the impact of tensions with the West by exploiting new revenue streams and export markets. The Kremlin additionally seeks to gain political allies on the continent, which helps mitigate Western isolation in international forums and advance Russian information narratives.

High-level Russian officials are visiting Russian partners across Africa to advance the Kremlin’s strategic goals of projecting greater Russian influence to supplant the West and better positioning Russia for prolonged confrontation with the West. Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov and Deputy Defense Minister Yunus Bek Yevkurov are separately visiting key Russian partners in Africa. Yevkurov’s trip began on May 31, when he arrived in eastern Libya, and has continued through at least June 3 with stops in Niger and Mali.[1] Lavrov arrived in Guinea on June 3 before traveling to the Republic of the Congo, Burkina Faso, and finishing with Chad on June 5.[2]

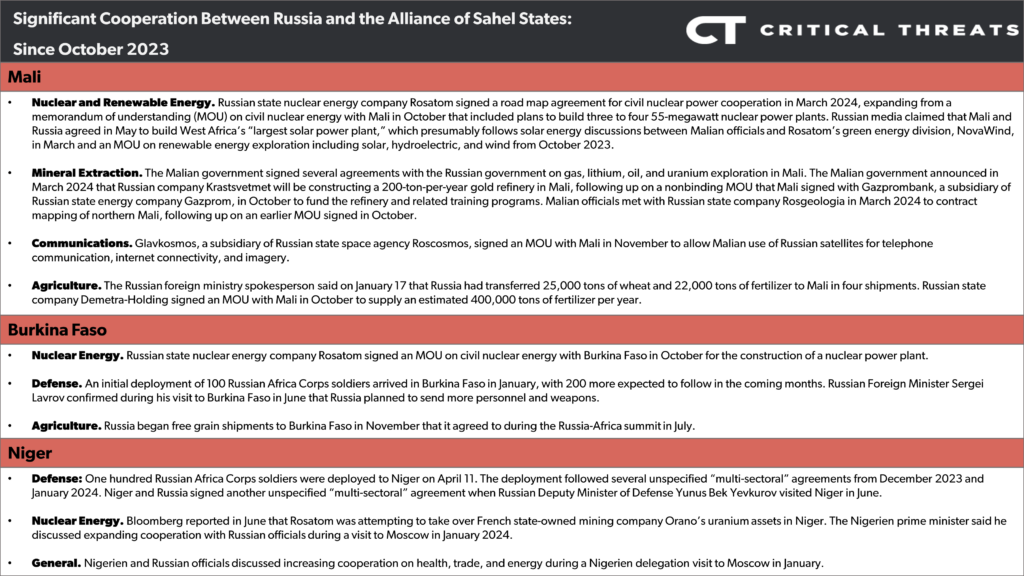

Figure 1. Russian Economic and Military Engagement in Africa

Note: Russian officials visited the labeled countries between May 31 and June 5. “SIPRI” is the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

Source: Liam Karr; European Parliament; Stockholm International Peace Research Institute; Africa Center for Strategic Studies.

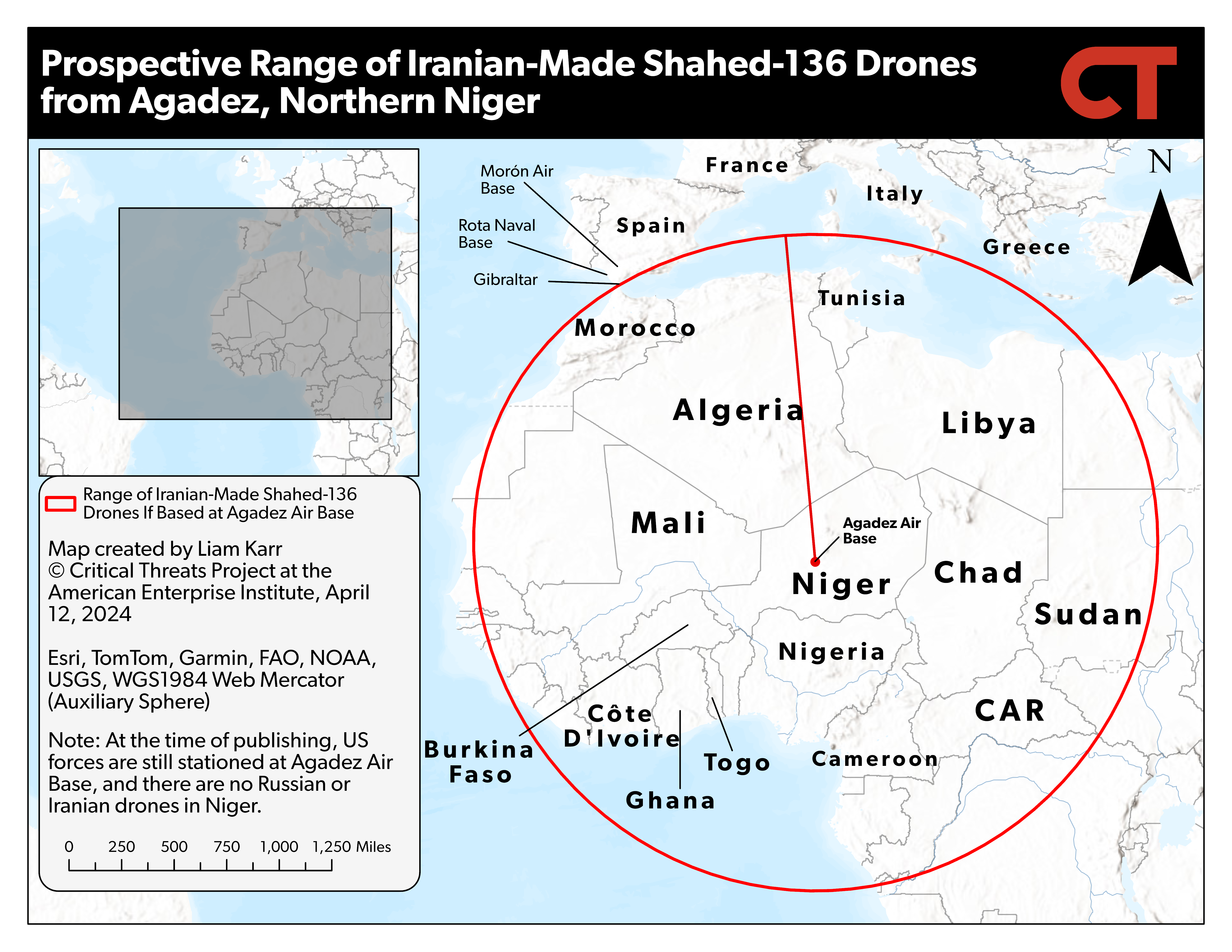

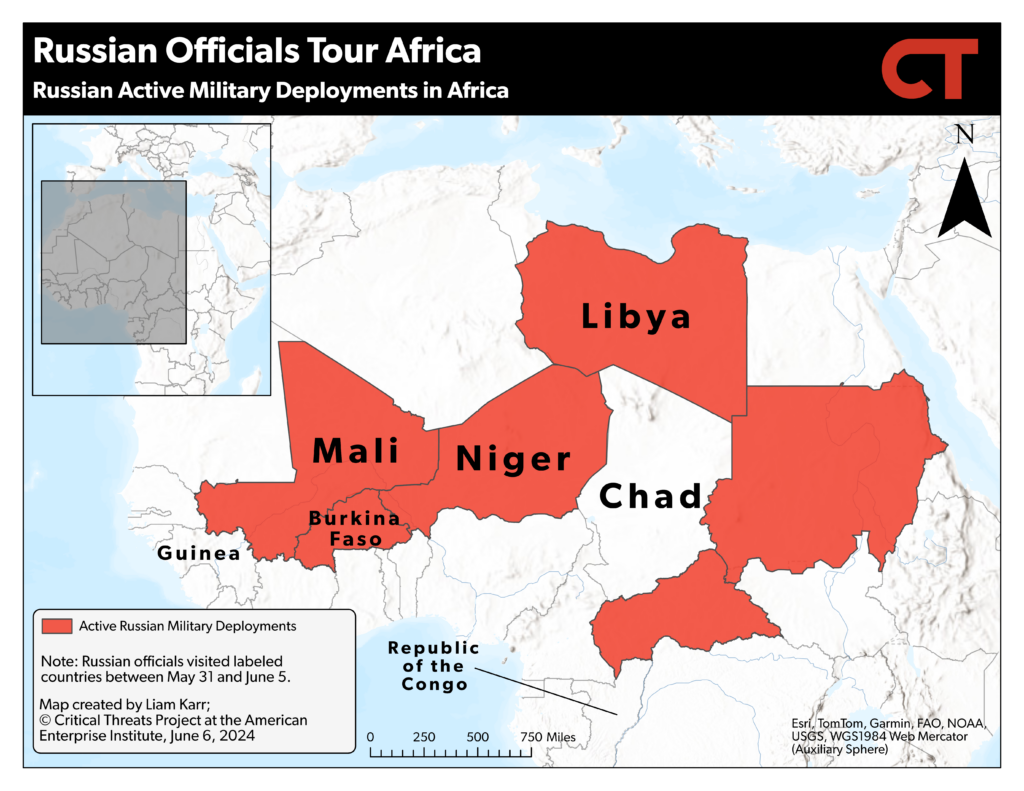

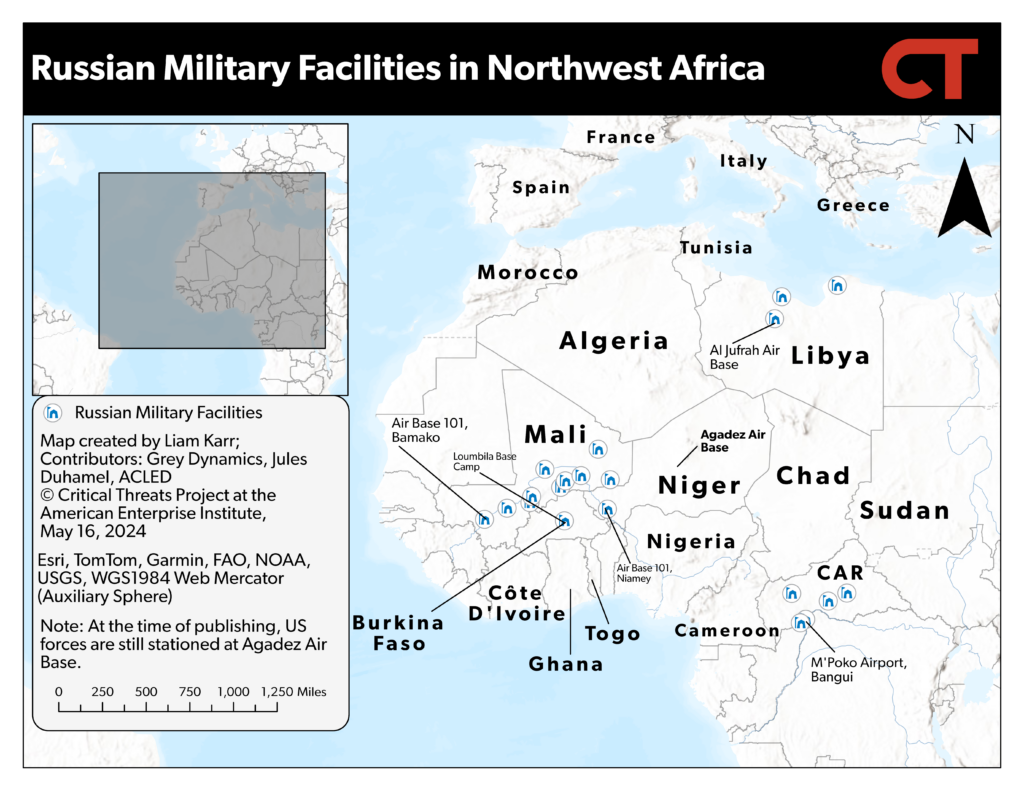

The visits are advancing Russian efforts to strengthen its military footprint on the continent. Yevkurov’s visits and Lavrov’s engagement with Burkina Faso likely intend to strengthen military cooperation in areas where Russian forces are already present. Yevkurov has been the face of Russian military engagement in Africa since the Russian Ministry of Defense (MOD) began subsuming Wagner Group operations under the MOD-controlled “Africa Corps” after the death of Wagner Group leader Yevgeny Prigozhin in August 2023.[3]

Yevkurov pledged to enhance the Libyan National Army’s capabilities during his visit.[4] Russia has already significantly reinforced Libya with nearly 1,800 new Africa Corps recruits and thousands of tons of military equipment since March, which CTP has assessed is likely related to Russian efforts to use Libya as a staging ground to reinforce its military deployments in sub-Saharan Africa and secure a naval base on the Libyan coast.[5] Russia also has 1,000–2,000 soldiers operating across Mali, supporting the Malian junta’s fight against al Qaeda–linked and IS-linked insurgents and Tuareg separatist rebels.[6]

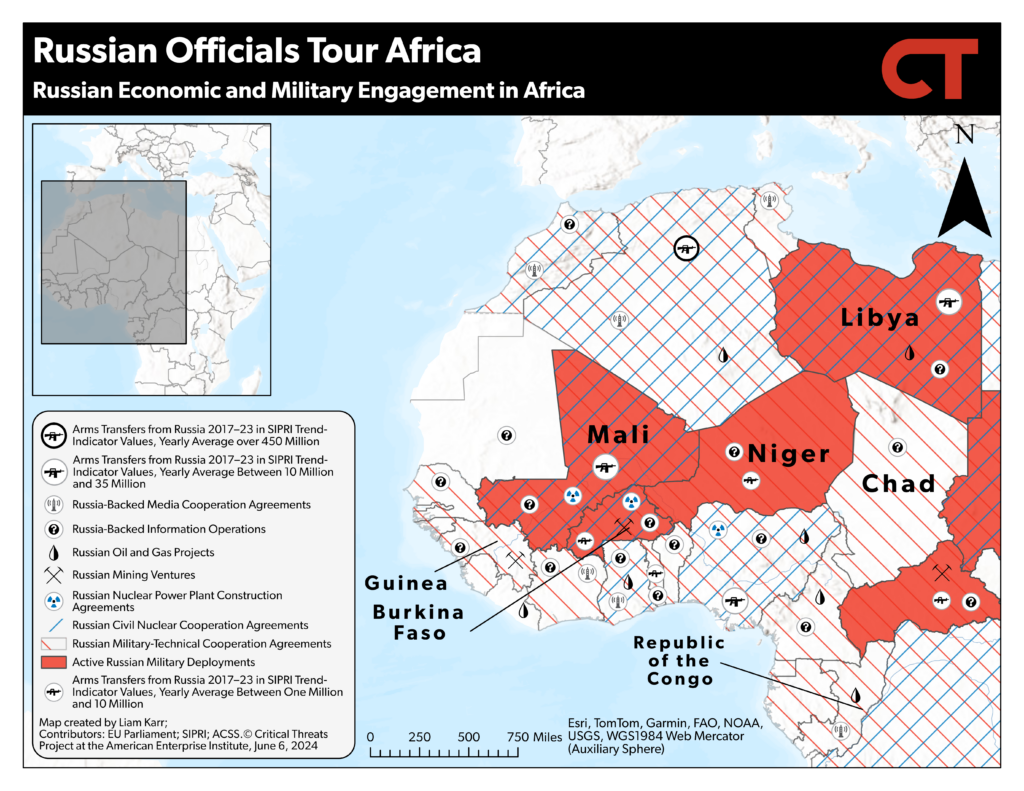

The Africa Corps also deployed initial batches of 100 soldiers to each of Burkina Faso and Niger in January and April 2024. The Niger contingent stated its intentions to replace US forces in northern Niger on arrival and entered a base housing US military personnel in the country in May 2024.[7] The United States plans to withdraw all forces from Niger by September 15, and US officials have noted that troops would be leaving behind stationary or bulky items such as hangars, housing units, generators, and other infrastructure.[8] Yevkurov signed a “multi-sectoral cooperation” agreement with Nigerien officials, which is the same terminology Russian media used to describe the agreement that paved the way for the initial Africa Corps deployment.[9] Lavrov also announced that Russia would send more military supplies and instructors to Burkina Faso, fulfilling Africa Corps–affiliated media claims from January that Russia planned to scale up the number of Africa Corps personnel in the country to 300.[10]

Figure 2. Russian Active Military Deployments in Africa

Note: Russian officials visited the labeled countries between May 31 and June 5.

Source: Liam Karr.

Lavrov’s visit to Chad aims to advance the Kremlin’s efforts to grow its relationship with the Chadian regime—including military ties—to establish itself as the primary partner across the entire Sahel and displace the West from the region. Former junta leader and now President Mahamat Deby visited Putin in Moscow in January 2024. The visit marked a reset of Chadian-Russian relations after Russia had supported Chadian rebels via the Wagner Group in previous years.[11] Chad asked for the handful of US troops in the country to leave pending a review of its military agreements with the United States in April.[12]

Putin offered security assistance to help “stabilize” Chad and promised greater political support for Chad in the UN.[13] He also offered to increase humanitarian aid and the number of Chadian students allowed to study in Russia.[14] Chad noted that Lavrov discussed counterterrorism and military cooperation as well as agricultural, educational, and humanitarian support during his visit, in line with these Putin’s initial promises.[15] CTP has previously assessed that aligning with Russia and the Russia-backed Sahelian juntas could pave the way for the Chadian junta to expand its defense and economic ties with Russia to address its own regime security needs and internal pressure to distance itself from the West.[16] However, Chad has also made efforts to balance ties with the West.[17]

The West is increasingly reliant on Chad after losing relationships with the central Sahelian states. Chad hosts France’s largest base on the continent and has received French troops that withdrew from Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger between 2021 and 2023.[18] French newspaper Le Monde reported in January 2024 that the United States was considering joint bases with France in Africa—presumably in Chad—as part of plans to adapt its security posture after it withdraws from Niger.[19] Future military cooperation between Chad and Russia would not necessarily exclude continued Chadian cooperation with Western partners, but it has repeatedly undermined such partnerships across the continent by driving a wedge between Western partners and host countries.[20]

Chad’s central location in the Sahel makes it important for all actors in the region, as it serves as a dam against—or potential bridge for—the fighters, weapons, and illicit networks surrounding it. In East Africa, the Sudanese civil war has created what numerous UN officials have labeled one of the worst humanitarian crises since World War II and increased concerns that Salafi-jihadi militants could gain a foothold and strengthen links between various al Qaeda and Islamic State affiliates operating in East and West Africa.[21] Russia has exploited the conflict to gain a Red Sea naval station, which it has long sought.[22] In West Africa, al Qaeda and Islamic State affiliates are exploiting the withdrawal of Western military support and the Russian-backed military regimes’ callous and unproductive military-first approaches.[23] A reduced Western footprint in Chad would limit Western options to address these threats.[24] Several of the countries where Russia has active forces border Chad, making it an efficient transit zone and logistics hub for the Kremlin.

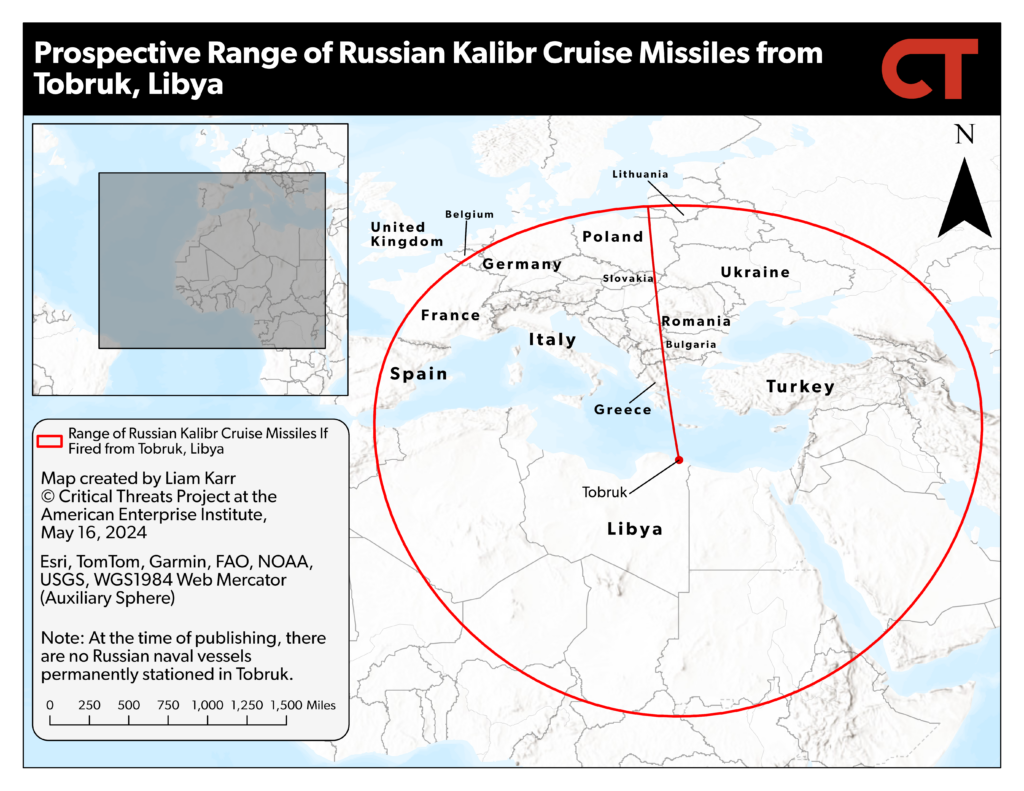

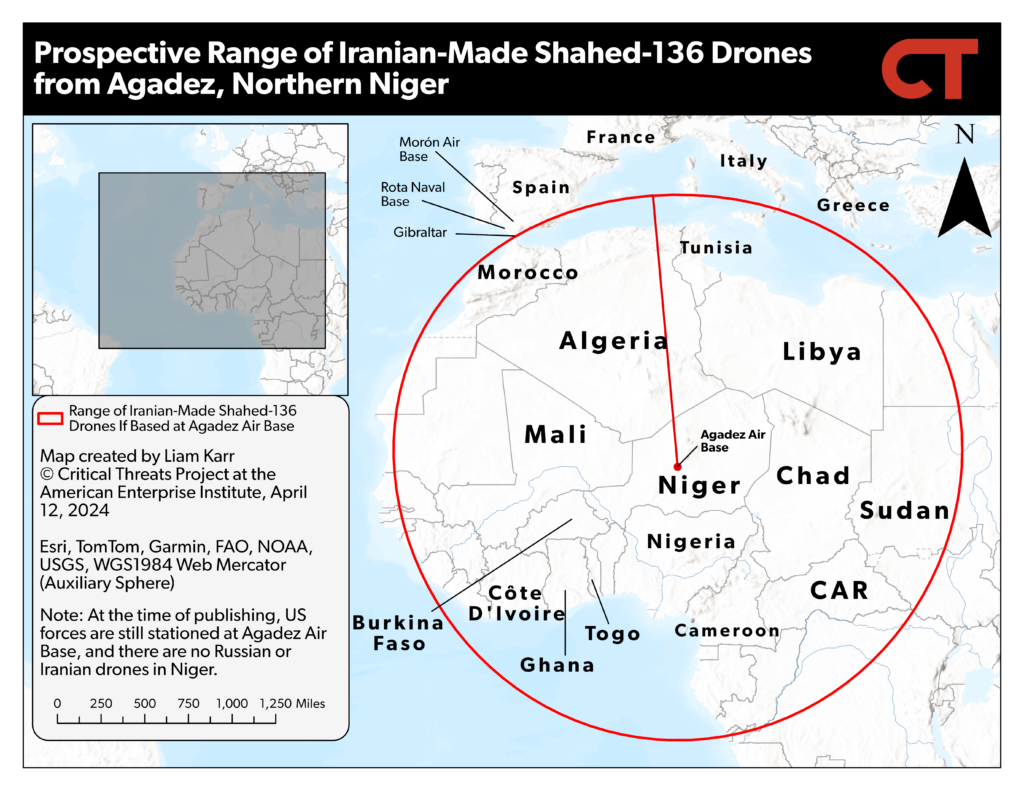

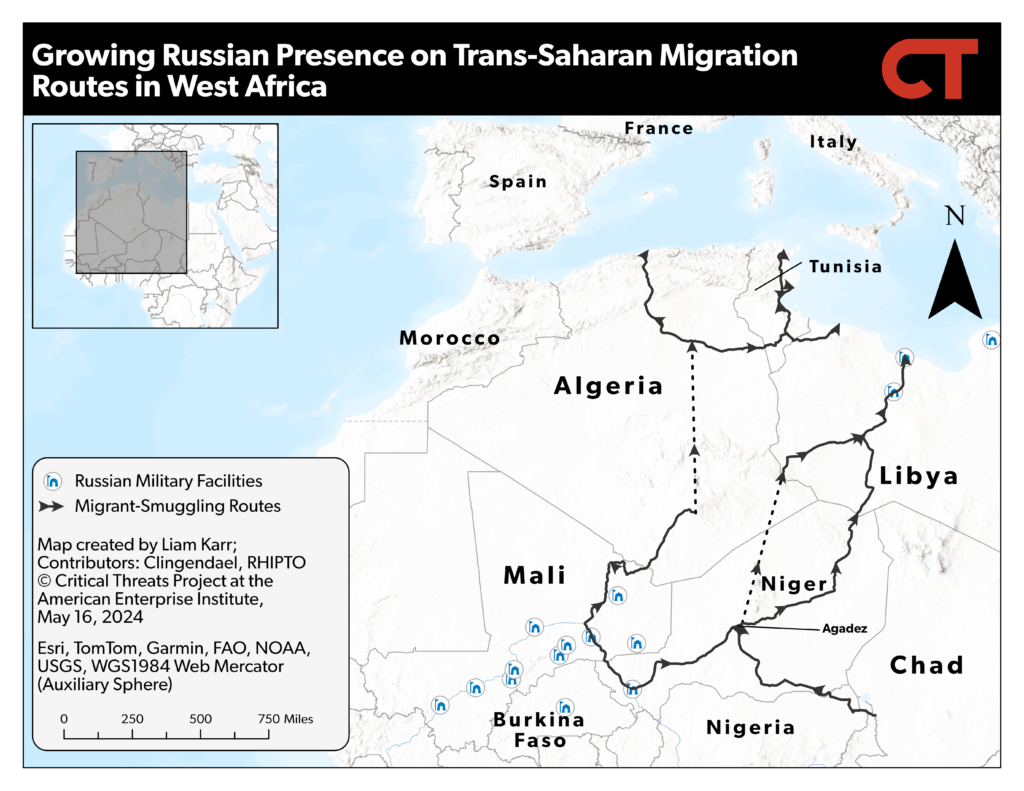

Russia’s growing military presence in Africa enables the Kremlin to use its limited resources to threaten NATO’s southern flank and degrade Western influence, advancing the narrative that Russia is a revitalized great power. A Russian naval base in Libya would threaten Europe and NATO’s southern flank by helping support Russian activity in the Mediterranean Sea and potentially positioning a standing Russian force able to threaten NATO critical infrastructure with long-range cruise missile strikes from the sea.[25] Russian occupation of the US drone base in northern Niger would create the opportunity for Russia to threaten NATO operations in the Mediterranean Sea with versions of the mass-produced Shahed-136 attack drone.[26] CTP has also previously assessed that the Kremlin will likely use its growing military footprint along key trans-Saharan migrant routes to weaponize migrant flows that risk destabilizing Europe.[27]

Figure 3. Prospective Range of Russian Kalibr Cruise Missiles from Tobruk, Libya

Note: At the time of publishing, there are no Russian naval vessels permanently stationed in Tobruk. “CAR” is Central African Republic.

Source: Liam Karr.

Figure 4. Prospective Range of Iranian-Made Shahed-136 Drones from Agadez, Northern Niger

Note: At the time of publishing, US forces are still stationed at Agadez Air Base, and there are no Russian or Iranian drones in Niger. “CAR” is Central African Republic.

Source: Liam Karr.

Figure 5. Growing Russian Presence on Trans-Saharan Migration Routes in West Africa

Source: Liam Karr; Clingendael Institute; Norwegian Center for Global Analyses.

Russia has advanced its goals of expanding its military footprint while degrading and denying Western access to the continent by targeting the West’s overreliance on France and security partnerships.[28] Russia has exploited and inflamed widespread anti-colonial sentiment in former French colonies to position itself as a natural alternative for populist juntas looking to distance themselves from the West.[29] Russia has spread its military presence as countries like Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger swap French assistance for Russian assistance.[30] The West also self-admittedly created excessively military-focused counterterrorism objectives as the foundation for its partnerships with several African countries.[31] Western security policies failed to address the underlying drivers of the insurgencies and linked the West to unpopular regimes. These outcomes enabled Russia to easily displace Western influence by offering an equal or greater degree of military support to nascent, populist, and anti-Western authoritarian regimes than the West is willing to provide.[32]

Figure 6. Russian Military Facilities in Northwest Africa

Note: “CAR” stands for Central African Republic.

Source: Liam Karr; Grey Dynamics; Jules Duhamel; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project.

Russia is also attempting to strengthen economic engagement with Africa in various sectors to mitigate the impact of tensions with the West by exploiting new revenue streams and export markets. The Russian delegations explored greater cooperation on infrastructure and natural resource extraction, presumably to increase Russia’s share of those revenue streams and export markets. Lavrov heavily emphasized Russia’s desire to grow economic ties with Chad and specifically highlighted transportation infrastructure projects.[33] He also announced that the Kremlin would send an economic mission to discuss such projects.[34]

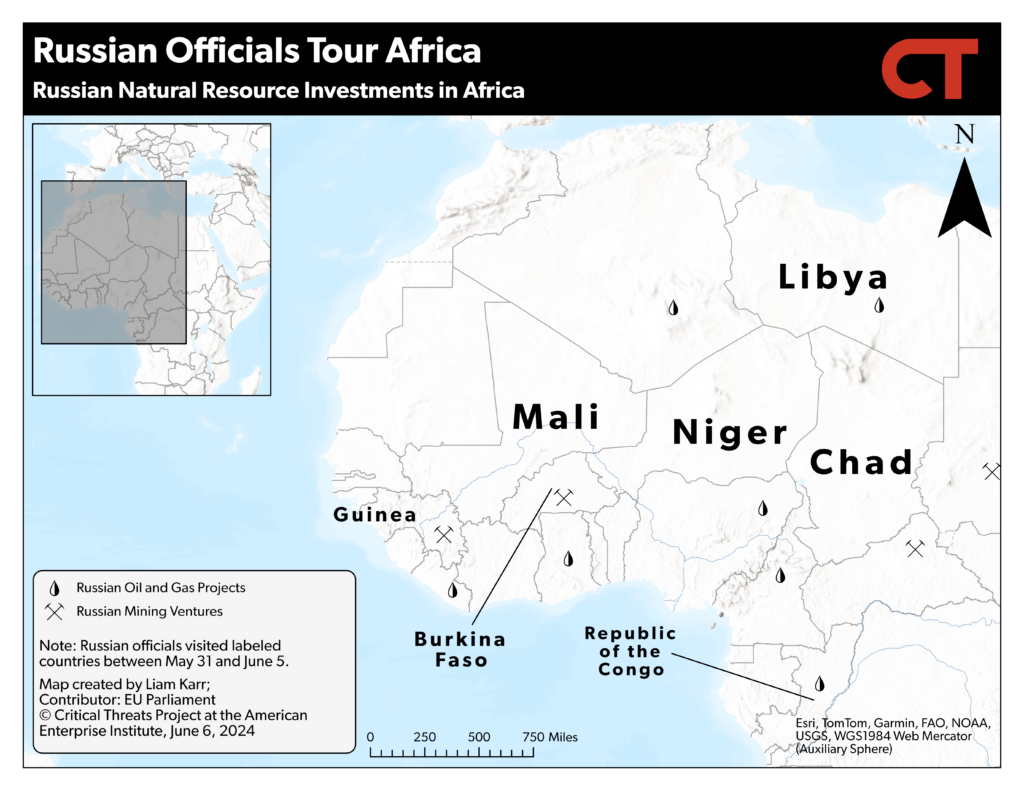

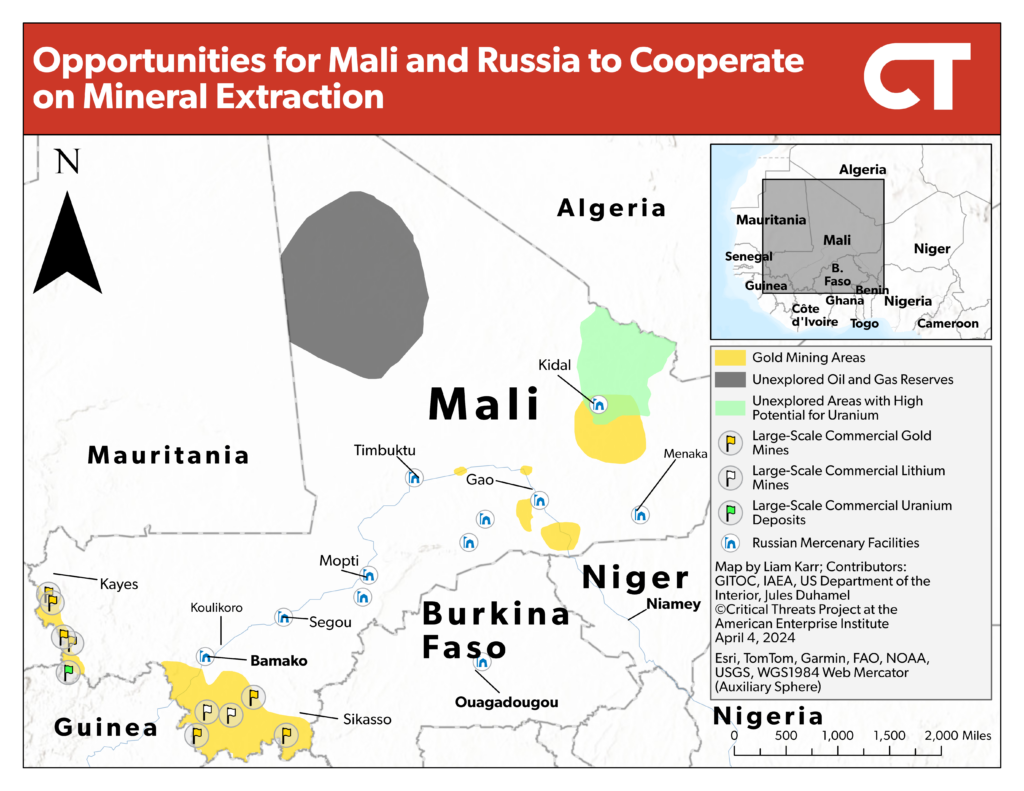

Russia has a complicated but solid working relationship with the Guinean junta due to Russia’s significant investment in Guinean mining of bauxite, a mineral that is refined into aluminum. The United States lists bauxite as a critical mineral, which means it has a high risk of supply-chain disruption or significant importance to manufacturing sectors.[35] Russia already has numerous investments in the Congolese energy sector, including liquefied natural gas (LNG) projects and oil pipeline construction.[36] Lavrov discussed future cooperation on geological exploration, development of mineral reserves, and energy in Chad and Congo.[37] Russian energy sector investors also accompanied Yevkurov to Niger and Mali, which presumably included oil and LNG investors. The Malian and Russian governments signed several cooperation agreements on oil, gas, uranium, and lithium production on March 31.[38]

Figure 7. Russian Natural Resource Investments in Africa

Note: Russian officials visited the labeled countries between May 31 and June 5.

Source: Liam Karr; European Parliament.

Figure 8. Opportunities for Mali and Russia to Cooperate on Mineral Extraction

Source: Liam Karr; Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime; US Department of the Interior; Jules Duhamel.

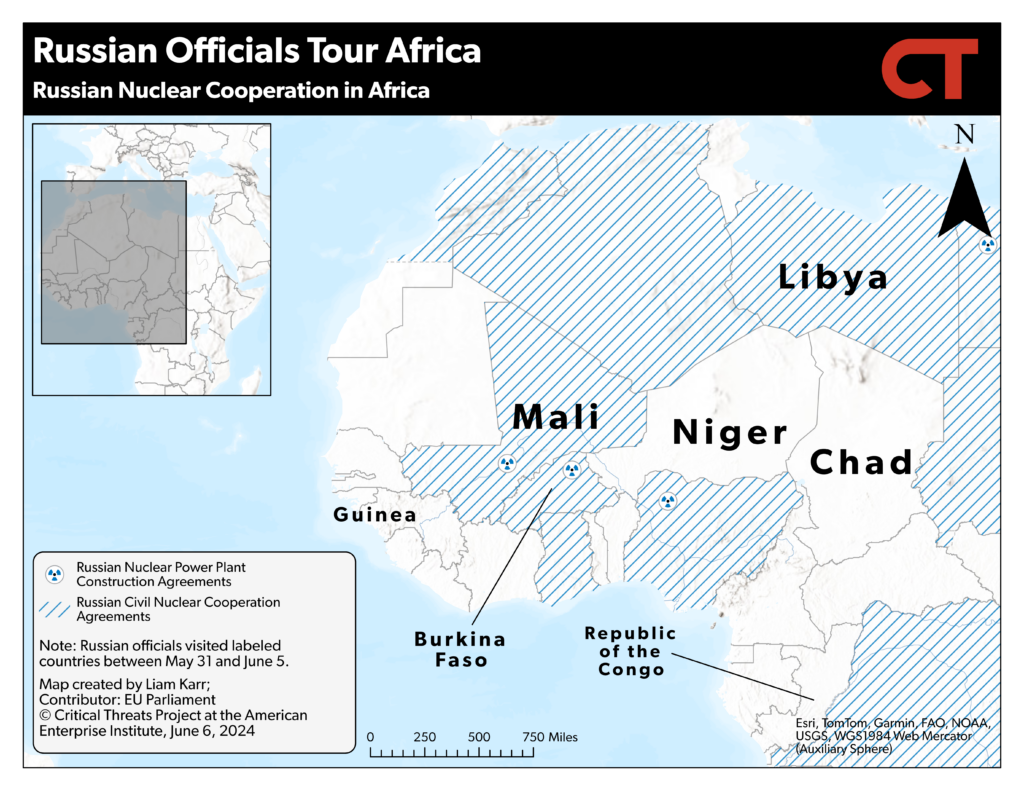

The Kremlin is also pursuing various aspects of nuclear energy cooperation in Africa to secure additional revenue streams and export markets. Russia has positioned itself as a global leader in the nuclear energy market, including in Africa.[39] This has led to numerous deals on peaceful nuclear technological cooperation and nuclear power plant construction.[40] These deals create multiple revenue and export market opportunities via Russia exporting nuclear energy technology, constructing power plants, and seeking to dominate the uranium market that power plants need to operate.

Nuclear energy was specifically an area of focus in the Sahel. Bloomberg reported shortly after Yevkurov’s visit that Russian state-owned nuclear energy company Rosatom is seeking to acquire uranium assets held by French state-controlled company Orano.[41] Lavrov also discussed nuclear energy cooperation with Burkinabe and Chadian officials. Burkina Faso signed an agreement with Rosatom in October 2023 on nuclear cooperation and the construction of a nuclear powerplant.[42] Lavrov also specifically noted that the Chadian president was highly interested in nuclear energy cooperation.[43]

Figure 9. Russian Nuclear Cooperation in Africa

Note: Russian officials visited the labeled countries between May 31 and June 5.

Source: Liam Karr; European Parliament.

Russia also likely seeks to boost its agricultural exports to Africa to boost revenue. Russia has attempted to capture a larger share of Africa’s wheat market since the late 2010s and has used its invasion of Ukraine to support this effort by targeting Ukrainian grain production and obstructing Ukrainian grain exports.[44] The Kremlin has subsequently tried to frame itself as a benevolent savior by donating some grain to African countries that are struggling with the resulting food insecurity.[45] Lavrov specifically discussed agricultural cooperation with Chad and Congo.[46]

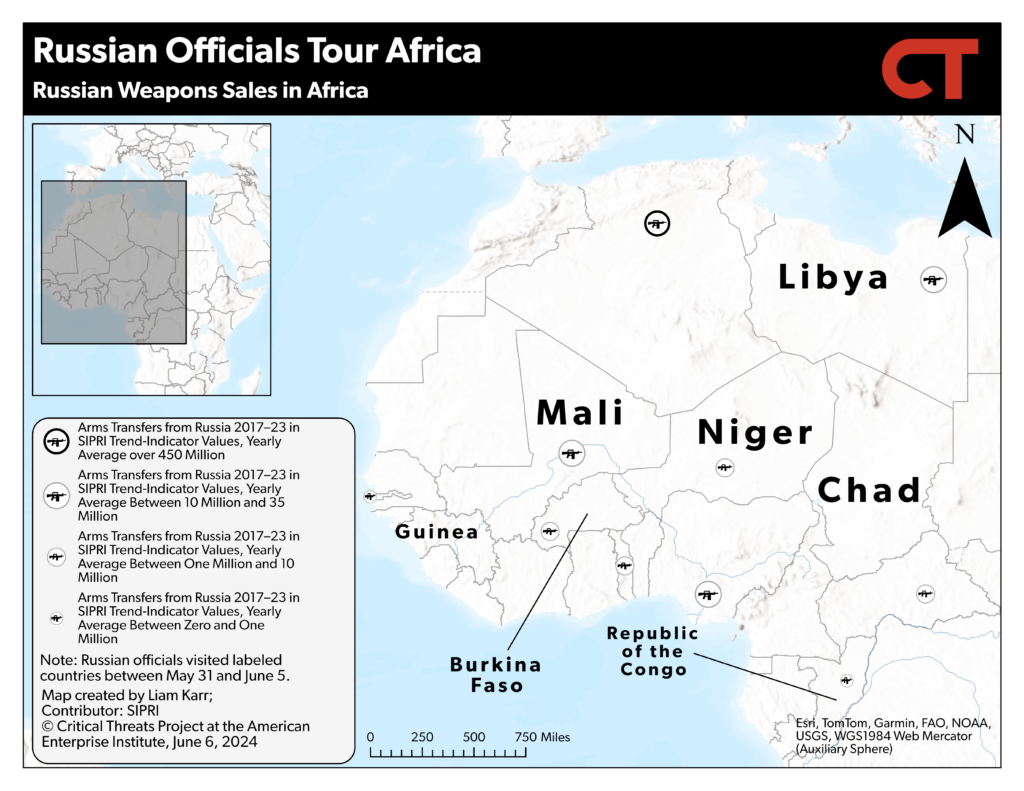

The Kremlin similarly aims to grow arms sales to Africa, which has the added benefit of advertising and boosting Russian military prestige. Lavrov said that Russia would tighten military-technical cooperation with Congo, which has since 2019 involved Russian trainers in Congo helping the Congolese military use, service, and repair Soviet and Russian military hardware, ensuring Congo remains a Russian weapons export market.[47] The countries that Yevkurov toured that have active Russian military deployments have similar military-technical agreements to boost cooperation between Russian and host forces. The Russian defense sector investors also accompanied Yevkurov to Niger and Mali, presumably to explore avenues for further arms and weapons system sales.[48]

Figure 10. Russian Weapons Sales in Africa

Note: Russian officials visited the labeled countries between May 31 and June 5. “SIPRI” is the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

Source: Liam Karr; Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

Increased Russian economic engagement in Africa provides Russia with new revenue streams and export markets to make the Russian economy more resilient in the face of Western economic retaliation for its invasion of Ukraine. Greater Russian access to African uranium would grow Russia’s control of the global supply market, thereby increasing its leverage with countries reliant on uranium purchases.[49] This strategy has already led to record-high Russian nuclear fuel exports in 2023, despite European efforts to divest from Russian fossil fuel purchases.[50] The Kremlin also mitigates the effects of Western sanctions on critical supply-chain minerals by acquiring lucrative resources in Africa.[51]

Russia also seeks to gain political allies on the continent, which helps mitigate Western isolation in international forums and advance Russian narratives. The Kremlin is attempting to undermine Western influence and create a network of authoritarian and pro-Russian African states that also politically gravitate toward Russia. The London-based Royal United Services Institute published a report in February 2024 highlighting how the Kremlin has internally described its military and economic engagement as a “regime survival package.” [52] This strategy involves leveraging formal state power and unconventional military units—such as the Africa Corps and Russian intelligence—to offer local elites military support, allyship in international bodies, and information campaigns to boost the elites’ domestic support.[53] Russia increases its influence over target governments and isolates them from the West as a result. This support also undermines democracy more broadly by insulating coup regimes from efforts to encourage a return to civilian rule, which erodes democratic values globally and thereby strengthens the Kremlin’s autocratic narrative.

The Kremlin uses its various partnerships to advance its aims in international bodies. Russian ties contributed to many African states taking neutral stances on punishing Russia for its invasion of Ukraine, helping de facto legitimize Russia’s violations of international law across one of the largest voting blocs in the UN.[54] French media also reported that Lavrov discussed the Libyan crisis with Congolese President Denis Sassou-Nguesso, who is head of the African Union High-Level Committee on the Crisis in Libya.[55]

Russian information operations spread by officials like Lavrov, Russian-affiliated African media, and social media undermine Western influence and Western values—like democracy—in the “global south” by positing Russia and other revisionist powers as anti-imperial allies against the “exploitative” West.[56] This rhetoric has latched onto preexisting and valid grievances with the West’s approach to engagement with the continent, especially in Francophone Africa, gaining Russia more popular support and allies among populist movements while obscuring Russia’s exploitative objectives.[57] Other revisionist powers, such as Iran, also spread this rhetoric, contributing to the popular and preexisting anti-colonial backlash against the West and its allies on diverse issues ranging from the New Caledonia independence movement to the Israel-Hamas war.[58]

Russia is most clearly creating a pro-Russian bloc that advances all its military, economic, and political aims in Africa in the Alliance of Sahel States (AES). The AES (l’Alliance des États du Sahel in French) comprises the three pro-Russian juntas in Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger. The juntas announced the alliance shortly after meeting with Yevkurov in September 2023, presumably securing the Kremlin’s blessing.[59] The Kremlin advances all its strategic objectives in Africa through the bloc. It is the primary security partner for the AES due to its strong military ties with all three countries, giving it a substantial military footprint across AES territory. Russia uses this partnership to create export markets for arms sales and has tightened cooperation in other economic sectors to advance its broader economic objectives. Lastly, its “regime security package” protects autocrats and ensures they remain in the Russian political orbit.

Figure 11. Significant Cooperation Between Russia and the Alliance of Sahel States