Key Takeaways:

- Sudan. Russia is planning to build a logistical support center on Sudan’s Red Sea coast, which it likely intends to use to advance its efforts to secure a Russian naval base in Sudan. Russia’s backing of the SAF aligns Iranian and Russian policies and strategies in the region. This enables the Kremlin to coordinate aid with Iran, which is already sending drones to the SAF. The shift may also free up Russian resources to use in Ukraine and other areas of Africa. Russia’s backing of the SAF additionally risks undermining impending US-backed peace talks.

- Sahel. Al Qaeda’s Sahelian affiliate increased the severity of its attacks in eastern Burkina Faso and along the Burkinabe-Nigerien border in May 2024, creating opportunities for the group to expand its support zones. The group’s growing pressure in southwestern Niger adds to Niger’s escalating security challenges as the Islamic State’s Sahel Province continues to strengthen and US forces prepare to withdraw from the country by September.

Assessments:

Sudan

Russia is planning to build a logistical support center on Sudan’s Red Sea coast, which it likely intends to use to advance its efforts to secure a Russian naval base in Sudan. SAF-backed Sovereign Council member and Assistant Commander in Chief Lt. Gen. Yasir al Atta announced on May 25 that Sudan and Russia will sign a series of military and economic agreements in the coming weeks. The agreements include the establishment of a Russian naval logistical support center in Sudan.[1] Atta confirmed that “Russia proposed military cooperation through a logistical support center, not a full military base, in return for urgent weapons and ammunition supplies” and agreed to expand cooperation to include economic aspects such as agricultural ventures, mining partnerships, and port development.[2] These talks likely happened when Russian Deputy Foreign Minister and Special Representative for the Russian President in Africa and the Middle East Mikhail Bogdanov met with the SAF head and other Sudanese leaders in late April.[3]

Russia has pursued a Red Sea port since 2008 to protect its economic interests in the area and improve its military posture vis-à-vis the West in the broader region, including in the Mediterranean Sea and the Indian Ocean.[4] Russian President Vladimir Putin and Sudan’s former dictator Omar al Bashir agreed in 2017 to a Red Sea base capable of stationing 300 Russian service members and four ships in exchange for various kinds of military and regime security support.[5] The Kremlin subsequently supported both the RSF and SAF after Bashir’s ouster in 2019 to pursue implementation of the deal.[6] RSF leader Gen. Mohamad Hamdan Dagalo, also known as Hemedti, led these negotiations after the RSF and SAF overthrew Sudan’s civilian-led transitional government in 2021, but the civil war that broke out between the RSF and the SAF once again put the deal on hold.[7] The SAF controls Sudan’s coast, making it the gatekeeper for any naval base.[8]

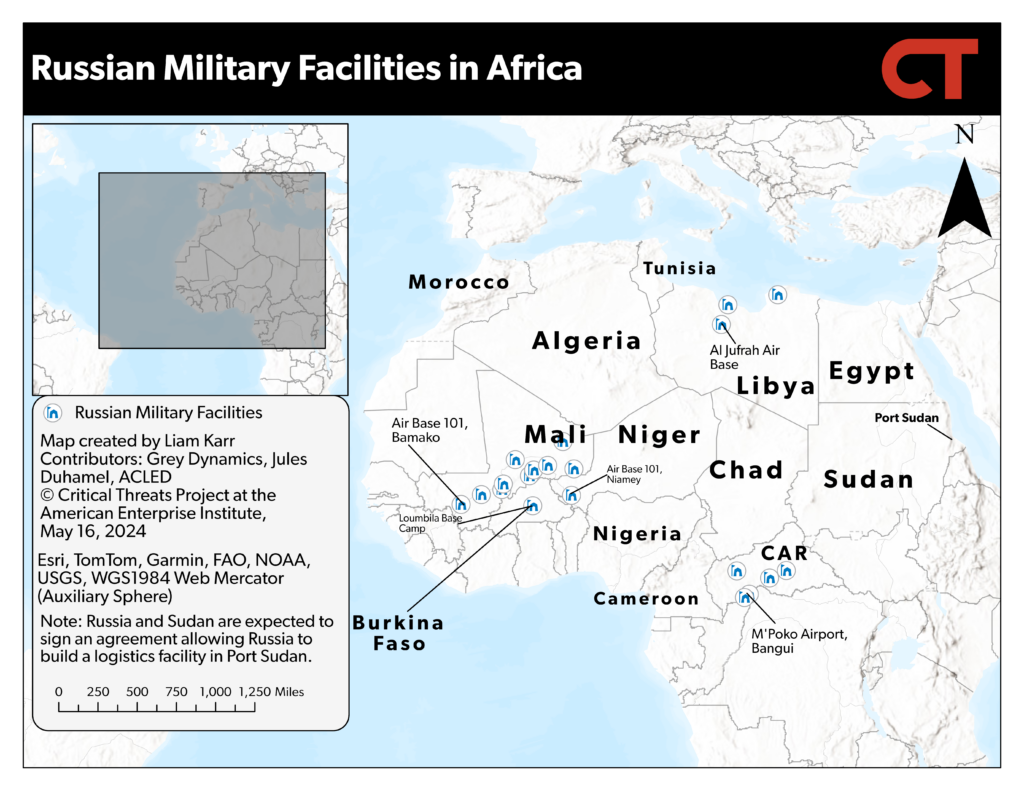

Russia will likely use the logistics center in Port Sudan to facilitate its own logistics activities in Africa. A logistics hub on the Red Sea does not significantly improve its existing network, however. Russia already has a naval base in Tartus, Syria, that it uses as a staging ground for logistics shipments to Africa.[9] The Kremlin primarily transports men and matériel from Tartus to Libya, which serves as a bridgehead for reinforcements and supplies destined for sub-Saharan Africa.[10] Port Sudan is farther from Russia’s various military deployments in the West African Sahel than is its existing bridgehead in Libya, and it is only marginally closer to its other primary area of operations in the Central African Republic.

Figure 1. Russian Military Facilities in Africa

Note: “CAR” is the Central African Republic.

Source: Liam Karr; Grey Dynamics; Jules Duhamel; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project.

The Kremlin likely primarily intends to use the logistics center and other deals to set the foundation for a naval base. Bogdanov specifically inquired about the preexisting port agreement during his meetings with Sudanese officials in late April, indicating it is still a primary objective of the Kremlin in Sudan despite repeated setbacks.[11]

The Kremlin may use logistical support to build favor with the SAF as part of a quid pro quo to eventually secure a full naval base. Bogdanov promised “unrestricted qualitative military aid” during his meetings with Sudanese officials in April.[12] Iran has similarly attempted to pursue its desire for a base through drone shipments and its offer of a ship.[13] However, the SAF rejected Iran’s offer so as to avoid alienating the West, illustrating the risks of this approach.[14] Sudanese leaders have also framed cooperation with Iran and Russia as a necessity due to a lack of support from other partners, including the West, underlining the transactional nature of this relationship.[15]

The Kremlin may also intend to use the logistics center and economic port infrastructure development deals to create a dual-use port. China has created numerous dual-use ports through its many deals to construct commercial trade ports.[16] China uses these projects to build commercial ports that also fit its naval military specifications, enabling it to potentially use commercial ports for military use in the future.[17] This method would allow Russia—and more importantly the SAF—to downplay the military significance of the port, possibly alleviating concerns about alienating the West. Russian officials announced plans for other similar commercial port infrastructure projects in Africa in March and April 2024, but Russia has historically not undertaken such large-scale efforts.[18]

The expected agreements between the Kremlin and SAF signal a significant shift in Russia’s approach to Sudan that will also presumably end or reduce support to the RSF, which opposes the SAF. Russia has had long-standing ties with SAF elements dating back to the reign of Bashir, but it was primarily supporting the RSF with training and matériel via the Wagner Group in the civil war that has been ongoing since April 2023. Russia supported the RSF to protect Russian interests in Sudanese gold that it has used to help fund its war in Ukraine and mitigate the impact of Western sanctions.[19] It is unclear how this relationship will continue with open Russian support for the SAF.

Russia may have already reduced support for the RSF since the death of Wagner Group leader Yevgeny Prigozhin in August 2023. The Russian Ministry of Defense has since subsumed Wagner’s Africa operations under the Ministry of Defense–controlled Africa Corps. There has been little reporting on Wagner Group or Africa Corps activity in Sudan since Prigozhin’s death, indicating a potential policy freeze and reevaluation period as the Kremlin balances state policy aims against Wagner’s previously more narrow business aims. The Kremlin has pivoted away from Prigozhin-era Wagner policies in Chad, where the Kremlin reset its policy in favor of another army strongman.[20] The civil war has also halted some Wagner-linked gold operations, decreasing Russia’s incentives to partner with the RSF for business purposes.[21] A Kremlin-affiliated milblogger explicitly framed the recent announcement of the Russian logistics port as the “collapse” of the image that Russia supports the genocidal RSF.[22]

Russia’s backing of the SAF aligns Iranian and Russian policies and strategies in the region. Iran has strengthened its bilateral relations with the SAF since late 2023 and started sending drones to the SAF in late 2023 and early 2024.[23] The Wall Street Journal reported in March 2024 that Iran unsuccessfully attempted to use these ties and promises of a helicopter-carrier ship to secure a permanent naval base in Port Sudan.[24] Iran seeks a Red Sea naval base for reasons similar to Russia’s—to project power farther westward. Iran would use a Red Sea base to support out-of-area naval operations and attacks on international shipping. This power projection includes threatening Red Sea shipping traffic and creating opportunities to launch attacks into Israel with systems fired from surface combatants.

Russia aligning with Iran would also enable the Kremlin to coordinate aid with Iran, which is already sending drones to the SAF.[25] Bogdanov met with Iranian Deputy Prime Minister Ali Bagheri Kani two days before leaving for Sudan, when they discussed “the importance of bilateral ties and regional issues,” indicating they are already coordinating on the issue.[26] Kani has since become the acting foreign affairs minister since the death of former Foreign Minister Amir Abdollahian in a helicopter crash on May 19.[27]

The shift in Russian support in favor of the SAF may free up Russian resources to use in Ukraine and other areas of Africa. Reliable Russian insider sources reported in mid-April that the Russian Ministry of Defense was planning to redeploy Russian soldiers from unspecified Africa Corps units to the Ukrainian border.[28] Numerous Telegram and intelligence sources have since reported in May that an unspecified number of Africa Corps forces consisting of new recruits, former Wagner Group fighters, and potentially African mercenaries are taking part in Russia’s recent offensive in Ukraine’s Kharkiv Oblast.[29]

The Kremlin has simultaneously strengthened positions across Africa throughout 2024. Russia has been reinforcing its position in Libya since March with approximately 1,800 Africa Corps troops and thousands of tons of supplies.[30] The Africa Corps also extended into Burkina Faso and Niger in January and March with small 100-troop deployments while expanding the main base supporting the roughly 2,000 soldiers operating across Mali.[31] Africa Corps–affiliated media said the group would grow the Burkinabe contingent to at least 300 troops and presumably plans to expand its footprint in Niger as US forces withdraw.[32] These growing demands compound ongoing capacity issues stemming from the Africa Corps’s ongoing recruitment drive falling short of expectations.[33]

Russia’s backing of the SAF also risks undermining US efforts to resume peace talks between the SAF and RSF. The United States has been urging a resumption of peace talks after US-Saudi efforts failed throughout 2023.[34] Other foreign interventions contributed to these failures by emboldening actors to take hard-line negotiating stances.[35] US Secretary of State Antony Blinken urged SAF leader Abdel Fattah al Burhan to resume negotiations in a phone call on May 28.[36] A high-ranking SAF-affiliated official has since criticized Blinken’s call and rejected the idea of peace talks.[37]

Sahel

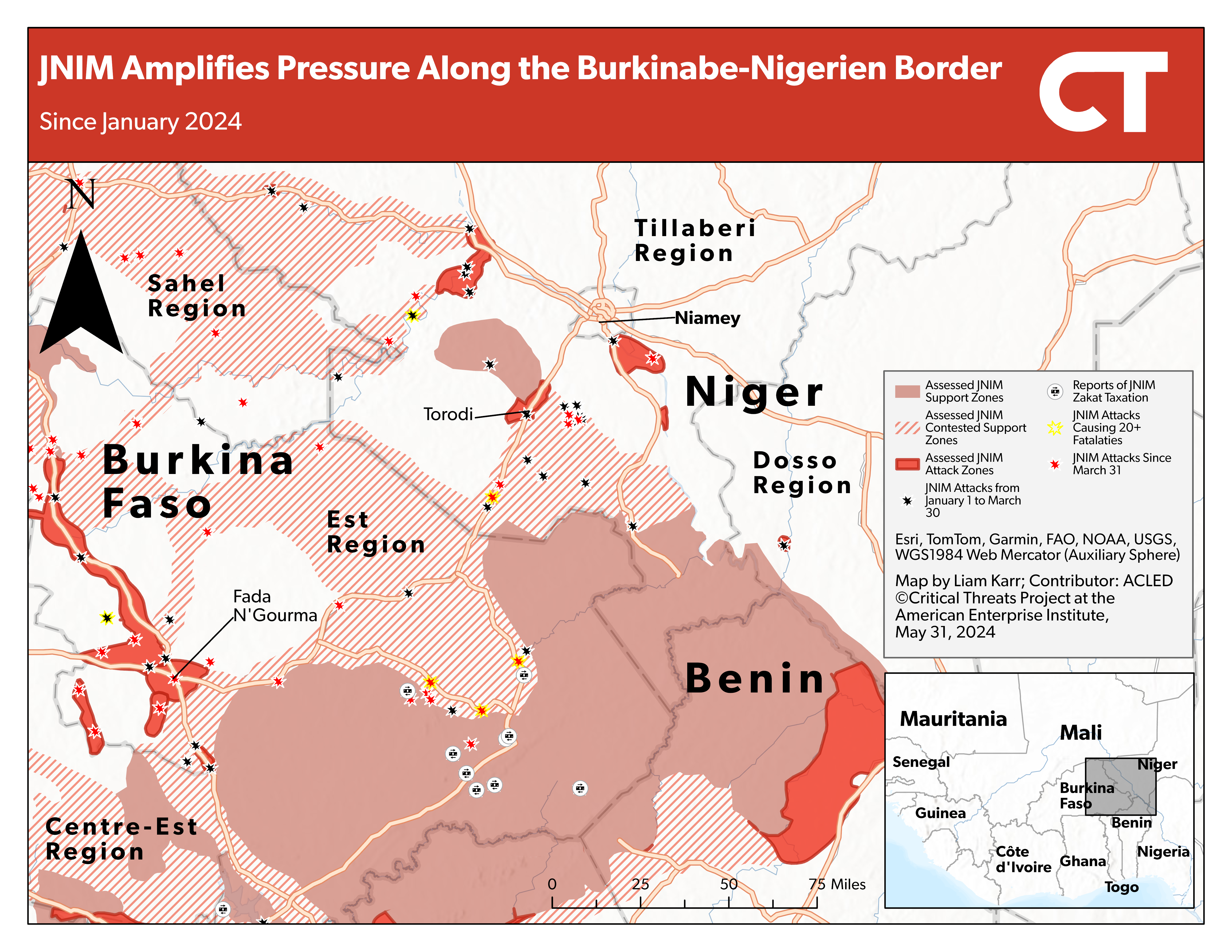

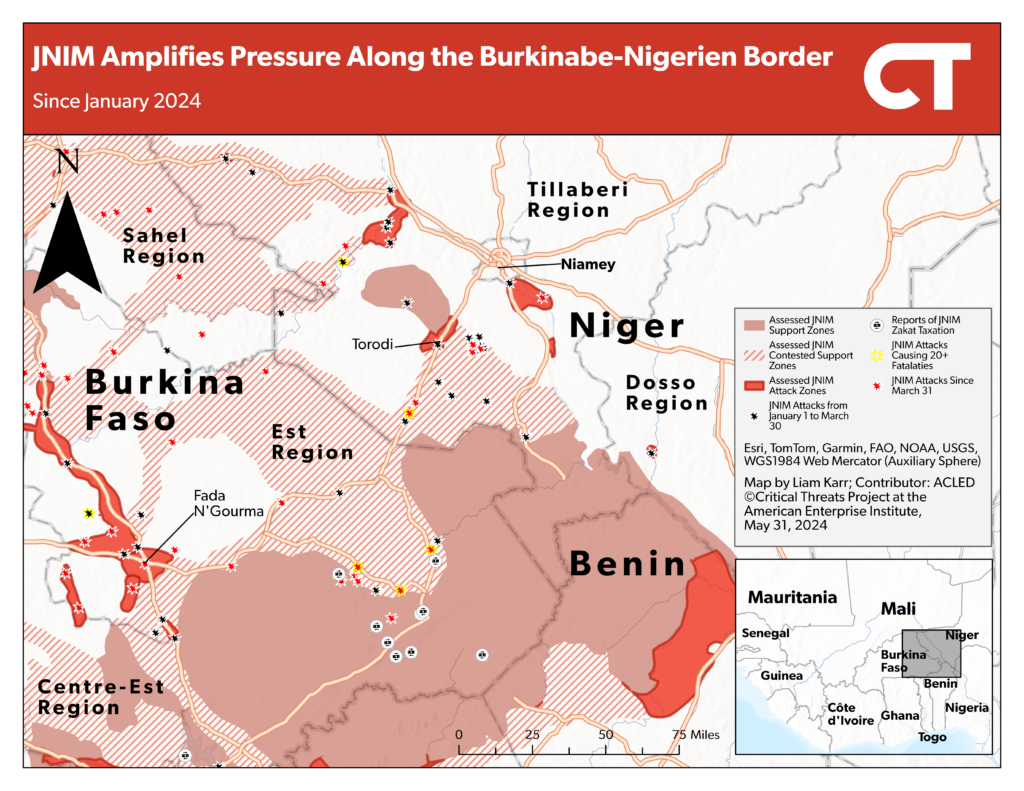

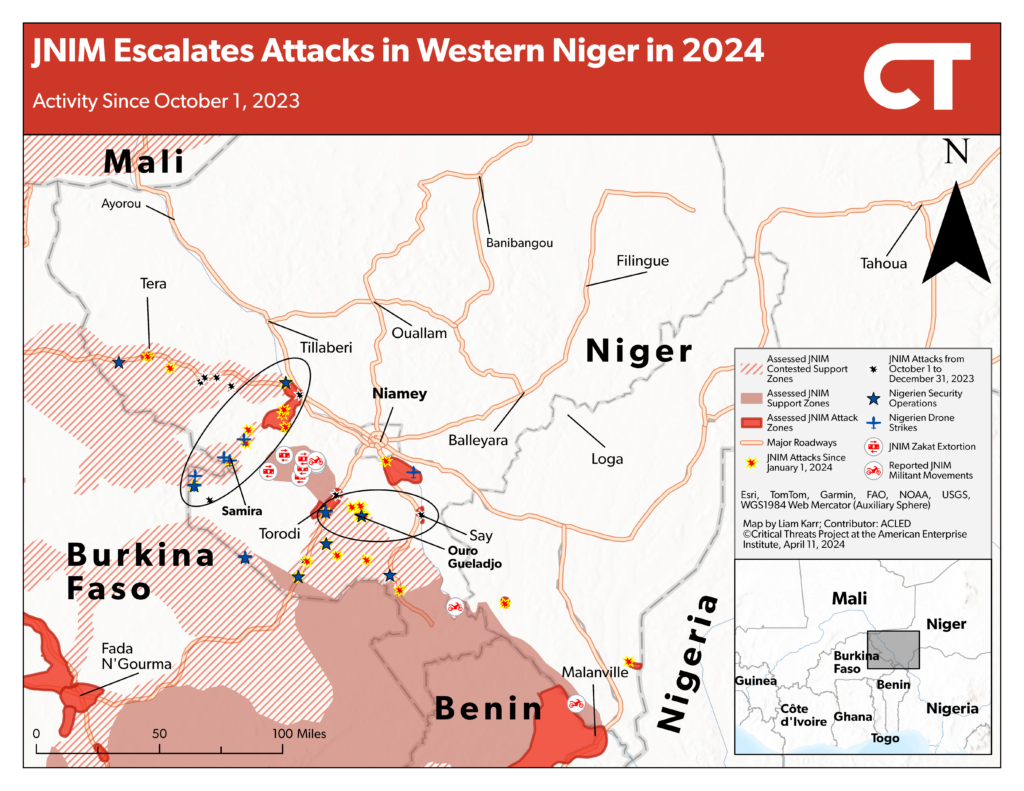

Al Qaeda’s Sahelian affiliate increased the severity of its attacks in eastern Burkina Faso and along the Burkinabe-Nigerien border in May 2024, creating opportunities for the group to expand its support zones. Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen (JNIM) carried out at least three large-scale attacks involving at least 100 fighters that killed at least 20 people in eastern Burkina Faso and along the Nigerien border in May.[38] This equals the total number of similarly sized attacks during the first four months of 2024.[39] The two biggest attacks each involved hundreds of JNIM fighters that targeted a gendarmerie and civilian auxiliary post in Burkina Faso on May 5 and a Nigerien army base on May 20 that killed over 50 people each.[40] The attacks have caused civilians to flee the towns and military forces to contemplate permanently abandoning targeted bases, creating opportunities for JNIM to fill the void.[41]

Figure 2. JNIM Amplifies Pressure Along the Burkinabe-Nigerien Border

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project.

JNIM likely consolidated support zones in eastern Burkina Faso in April that are helping facilitate these attacks. The group launched another large-scale attack on March 31 that overran a Burkinabe base and nearby town, killing 73 soldiers, civilian auxiliaries, and unarmed civilians.[42] JNIM then decreased the severity of its attacks throughout April while local reports of governance activity in nearby areas increased, such as tax collection.[43] The group is presumably using these support zones as staging grounds for the hundreds of fighters involved in the large-scale attacks.

JNIM will likely use additional large-scale attacks to expand its support zones, enabling it to carry out more frequent and severe attacks against isolated Burkinabe and Nigerien security forces that will disrupt lines of communication and besiege major population centers. Stronger JNIM support zones along both sides of the Burkinabe-Nigerien border would support JNIM’s effort to establish a foothold in southwestern Niger. The group has heavily contested Nigerien forces near Ouro Gueladjo since July 2023 to consolidate rural support zones in the area.[44] Such support zones would enable JNIM to target several important lines of communication in southwestern Niger between nearby department capitals and the capital, Niamey.[45] JNIM would also use such support zones to target roads connecting southeastern Burkina Faso and southwestern Niger that military and civilian convoys use.[46]

Figure 3. JNIM Escalates Attacks in Western Niger in 2024

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project.

JNIM is already besieging several towns in eastern Burkina Faso and has regularly used siege campaigns to force smaller localities into negotiations or isolate security forces and civilians in large population centers.[47] Sieges demonstrate that the state cannot protect civilians or provide basic services, and they often lead civilians to flee for large government-held towns or negotiate with JNIM to cut cooperation with security forces in exchange for protection.[48] These agreements isolate security forces from the communities they need to protect and win over to defeat an insurgency. Losing community support also degrades security forces’ ability to gather local intelligence to defend themselves from imminent attacks. Stronger support zones will also grow the available resources and space JNIM needs to organize major attacks and smaller-scale roadside ambushes—and the improvised explosive device attacks that underpin these sieges.

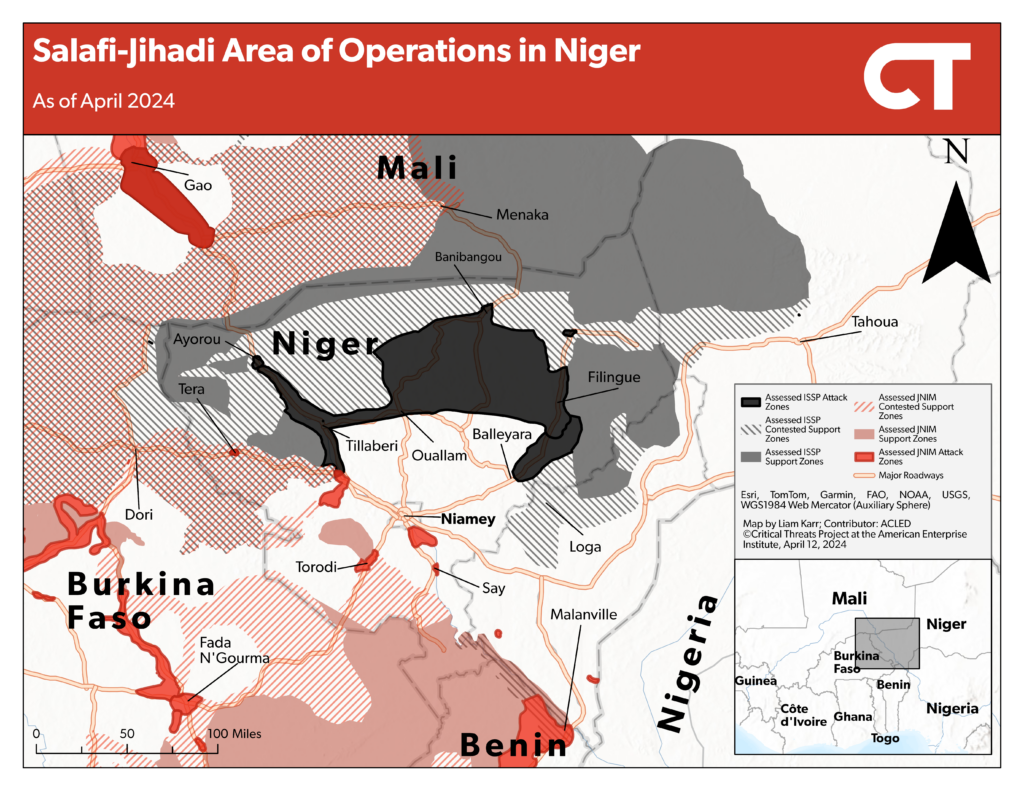

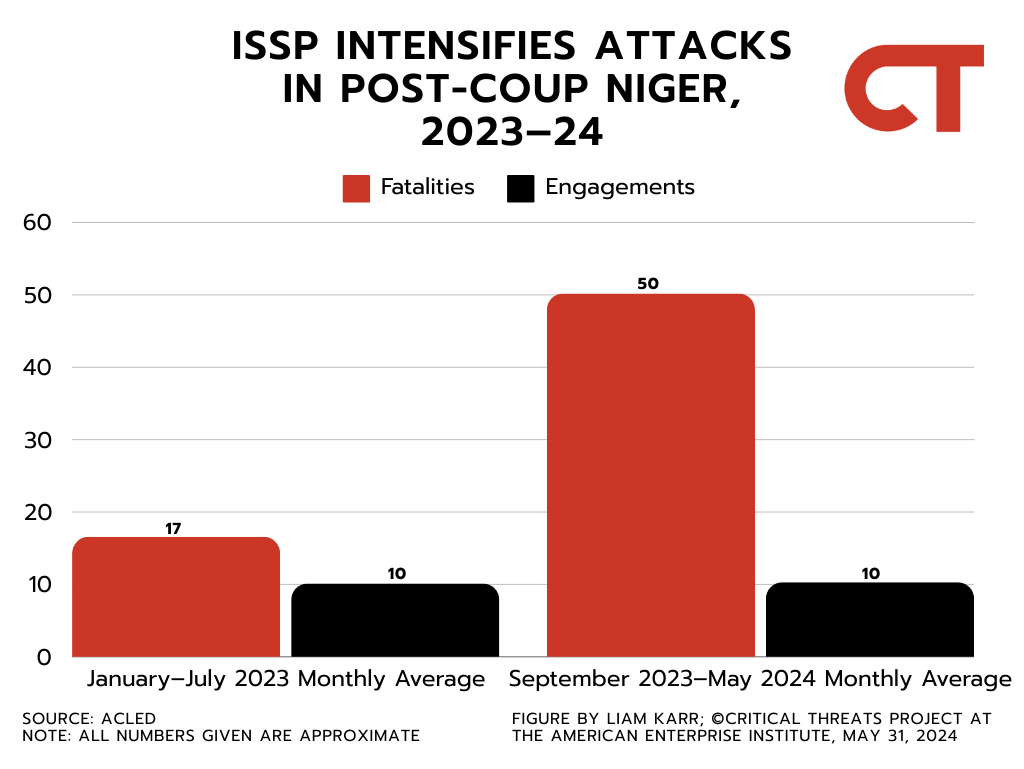

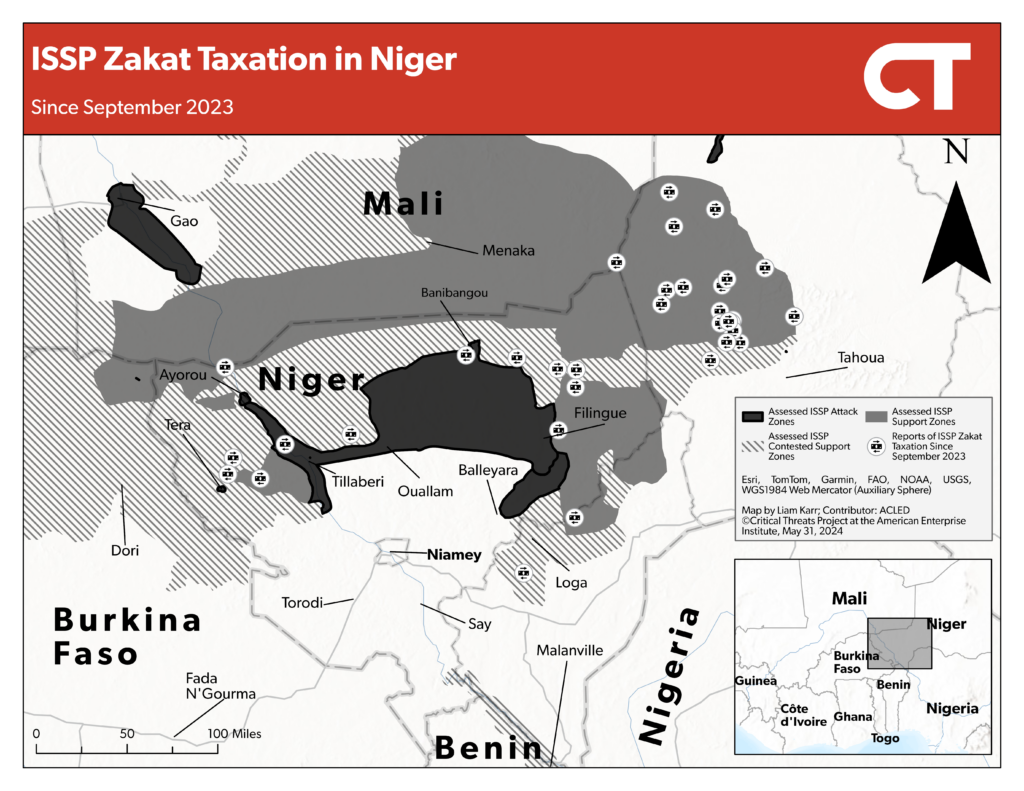

Growing pressure from JNIM in southwestern Niger exacerbates growing security challenges in Niger as the Islamic State’s Sahel Province (ISSP) continues to strengthen and US forces prepare to withdraw. ISSP has significantly increased the severity of its activity since the July 2023 Niger coup, averaging nearly five times as many fatalities per month since the coup. ISSP has simultaneously expanded the geographic scope and rate of taxation of civilians in northern Niger.[49] Both trends indicate that ISSP has significantly expanded and strengthened its support zones and control over civilians in the absence of security forces. The group’s growing strength in Niger and across the border in Mali has enabled it to establish itself as a hub for IS global activity, including for foreign fighters and media promotion.[50]

Figure 4. ISSP Intensifies Attacks in Post-Coup Niger, 2023–24

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project.

Figure 5. ISSP Zakat Taxation in Niger

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project.

The United States announced it would withdraw its forces from Niger by September 15 after Niger annulled defense cooperation with the United States in March, which will exacerbate these already growing threats.[51] The loss of US support will remove US equipment, training, and support programs for Nigerien transport aircraft and permanently end US intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) support.[52] The United States had already indefinitely suspended ISR support for Nigerien forces after the coup, which has likely contributed to the increased severity of IS attacks. The decrease in Western ISR support in Mali since France withdrew in 2022 has significantly improved Salafi-jihadi militants’ freedom of movement, enabling militants to gather in larger numbers and attack security forces with less warning than before, increasing the scale and severity of their attacks.[53]

Figure 6. Salafi-Jihadi Area of Operations in Niger