Key Takeaways:

Libya. Russia has reinforced its military presence in Libya as it consolidates its positions across Africa. Russia may have deployed the influx of personnel and matériel as part of ongoing negotiations to secure a naval base in Libya, prepare to send more support to various theaters in sub-Saharan Africa, or strengthen its position to make itself essential to resolving the ongoing domestic stalemate in Libya. None of these potential causes are mutually exclusive. The Kremlin likely aims to protect its position in Libya so that it can use Libya’s strategic location to pose conventional and irregular threats to Europe and continue using it as a logistical bridgehead for activities in sub-Saharan Africa.

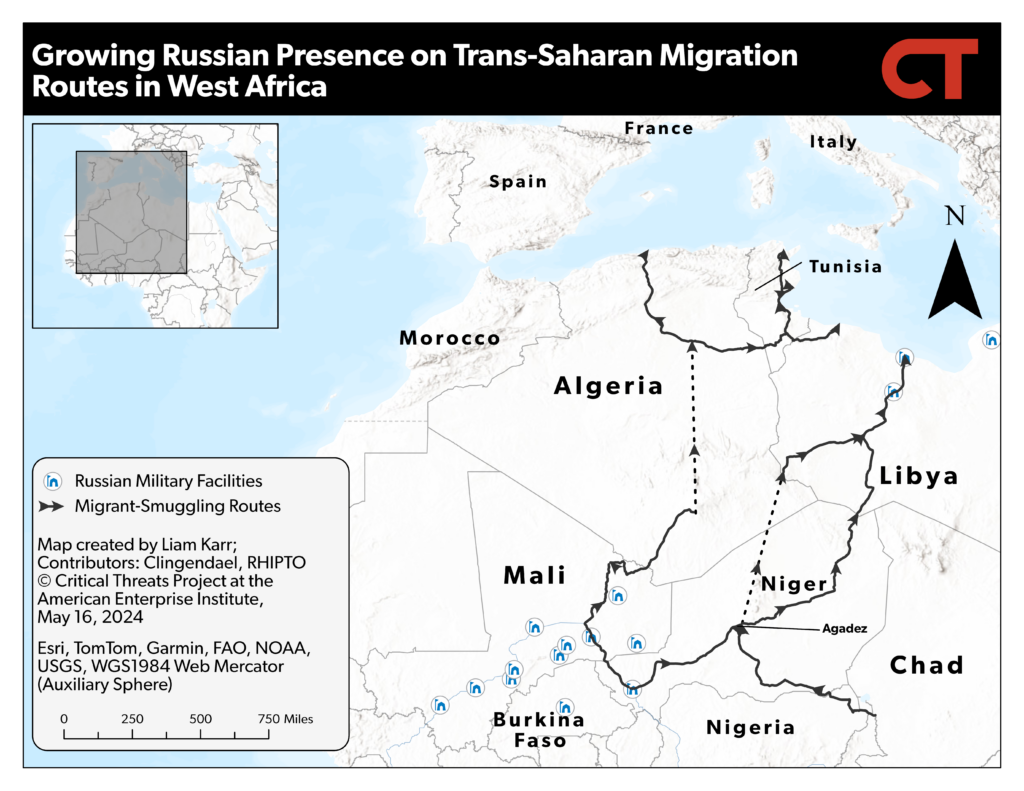

West Africa. Russia has recently expanded military cooperation with former Portuguese colonies in West Africa as it continues to expand its influence in Africa. Russia is likely trying to spread its influence from the landlocked Sahel and Central African Republic (CAR) into key waterways for regional and transatlantic shipping. The Kremlin may also seek to undercut African support for Ukraine as a secondary goal. Russian Atlantic basing in West Africa is a potential but less direct alternative to Mediterranean basing to threaten NATO’s flank.

Iran. Iran is using weapons sales to pursue uranium in Africa. French media has continued reporting that Iran and Niger have been negotiating since the end of 2023 for Niger to provide 300 tons of uranium yellowcake to Iran in exchange for drones and surface-to-air missiles. Iran is also likely using defense engagement to pursue uranium or other minerals in Zimbabwe. Iran has increased outreach to Zimbabwean officials since the beginning of April and has been aiming to grow cooperation in critical areas for uranium, like energy and mining, since 2022.

Mozambique. The Islamic State’s Mozambique Province conducted one of its largest and most complex attacks in years as it continues to operate at a scale unseen since at least 2022. The group is likely demonstrating its strength as regional security forces prepare to depart. Future security force arrangements are unstable and likely insufficient to degrade the insurgency. An escalation of the insurgency threatens to strengthen the global IS network and undermine local and international economic development.

Assessments:

Libya

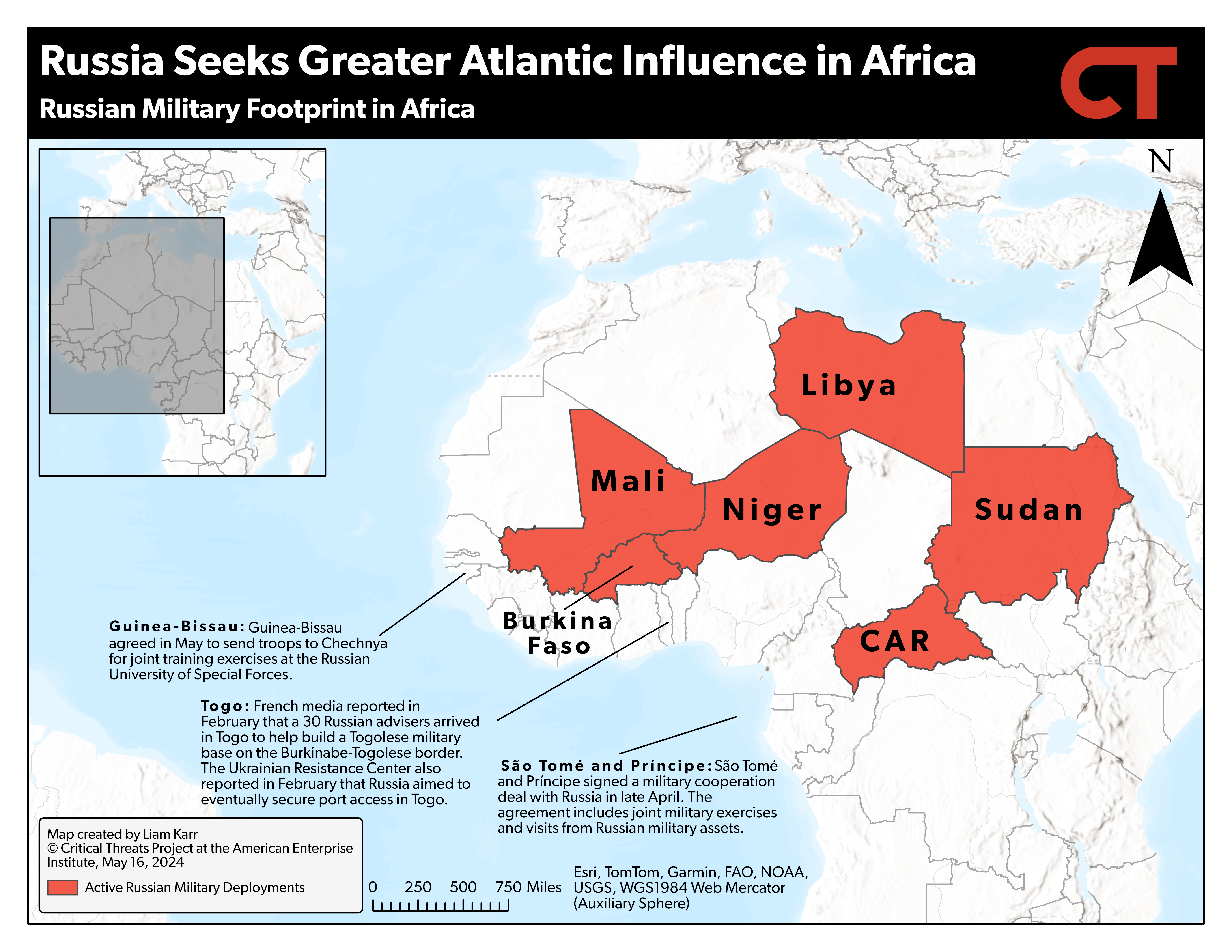

Russia has reinforced its military presence in Libya as it consolidates its positions across Africa. Open-source intelligence project All Eyes on Wagner, opposition Russian outlet Verstka, and Radio Free Liberty published a joint investigation on May 10 that details a surge of Russian military personnel and supplies since March 2024 to parts of Libya controlled by the Libyan National Army (LNA). The report said that Russia deployed over 1,800 soldiers to Libya in the past two weeks and transferred several hundred special forces from Ukraine to Libya earlier in 2024.[1] The non–special forces soldiers are either ex–Wagner Group personnel or fresh recruits to Africa Corps, the Russian Ministry of Defense’s successor to Wagner in Africa.[2] This surge more than doubles the estimated 800 Russian troops present in Libya at the beginning of 2024.[3]

Russia has also sent thousands of tons of supplies from its port in Tartus, Syria, to Tobruk, Libya, with at least five shipments in the past 45 days.[4] One shipment in April alone accounted for 6,000 tons of military hardware.[5] These shipments included equipment, vehicles, and weapons, including radar systems, T72 tanks, armored personnel carriers, and artillery systems.[6] Russia has supported the LNA and its leader Khalifa Haftar for years, but Russian Ministry of Defense sources claimed in the investigation that the recent surge is the most significant shift in Libya since the Ukraine war began.[7]

Russia may have deployed the influx of personnel and matériel as part of ongoing negotiations to secure a naval base in Libya. The Russian Ministry of Defense has intensified discussions for a Russian naval base in Libya, specifically Tobruk, since assuming control of the Wagner Group’s operations after the death of former Wagner leader Yevgeny Prigozhin in August 2023.[8] Russian Deputy Defense Minister Yunus-Bek Yevkurov, who took over Russian military operations in Africa, met with Haftar four times between August 2023 and January 2024.[9] Russia reportedly offered air defense systems and pilot training in exchange for the base, according to a 2023 Bloomberg report.[10]

The Kremlin is already de facto using Tobruk as a logistical bridgehead and is also likely preparing to send more support to various theaters in sub-Saharan Africa with the current buildup. Russian forces and supplies arrive in Tobruk before traveling to Djoufra, Libya, where they then deploy to sub-Saharan locations.[11] The Kremlin has expanded its sub-Saharan operations in 2024, sending two small contingents of 100 soldiers each to Burkina Faso and Niger in January and March, respectively.[12] Russian sources said the Burkinabe contingent would eventually grow to at least 300 soldiers, which has not yet happened.[13] The small group of Russian troops in Niger is already stationed near withdrawing US forces in Niamey and has indicated that it wants to replace US forces in northern Niger as well.[14] Russia growing these small deployments still does not alone explain the transfer of 2,000 soldiers to Libya.

Thousands of Russian soldiers are also active in the CAR, Mali, and Sudan. Russian forces in Sudan had been materially supporting the Rapid Support Forces against the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) in the Sudanese civil war, but CTP recently assessed that the Kremlin may be looking to switch its support.[15] Sudanese press said that the Russian Deputy Foreign Minister and Special Representative for the Russian President in Africa and the Middle East Mikhail Bogdanov offered the SAF “unrestricted qualitative military aid” when visiting with SAF officials in late April.[16]

Figure 1. Russian Military Facilities in Northwest Africa

Source: Liam Karr.

The Kremlin may also be positioning itself as essential to resolving the ongoing domestic stalemate in Libya through continued support for both factions. Russia has deepened its engagement with the rival UN-backed Government of National Accord (GNA) during the past year. The GNA controls western Libya from Tripoli and is supported by militias fighting the LNA and the LNA-backed government that controls eastern Libya from Tobruk, the Libyan House of Representatives.[17] Russia claimed to reopen its embassy in Tripoli in July 2023 and resumed full-staff work in February 2024.[18] Russian President Vladimir Putin also had a meeting with the GNA head during the 2023 Russia-Africa summit.[19]

Pro-Western and pro-Russia analysts have agreed that the Kremlin has historically sought to strengthen ties with various Libyan actors to improve its leverage over both factions and make itself indispensable to eventual peace talks.[20] Russia also plans to reopen a consulate in LNA-controlled Benghazi to complement the embassy in Tripoli, for example.[21] The Russian ambassador had already been staying in hotels in Benghazi and Tripoli to advance continued diplomatic outreach to both sides despite lacking official facilities.[22] Bogdanov also separately met with both Haftar and GNA officials in Libya in May and reportedly discussed peace efforts and bilateral cooperation.[23]

The Kremlin likely aims to protect its position in Libya so that it can use Libya’s strategic location to pose conventional and irregular strategic threats to Europe in addition to its current function as a logistical bridgehead. A Russian Mediterranean base in Libya would threaten Europe and NATO’s southern flank. A Libyan base would immediately enable Russia to expand its military footprint and offset Turkey’s closing of the Bosporus and Dardanelles since the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, which prevents Russia’s Black Sea Fleet from supporting Russian activity in the Mediterranean and Syria.[24]

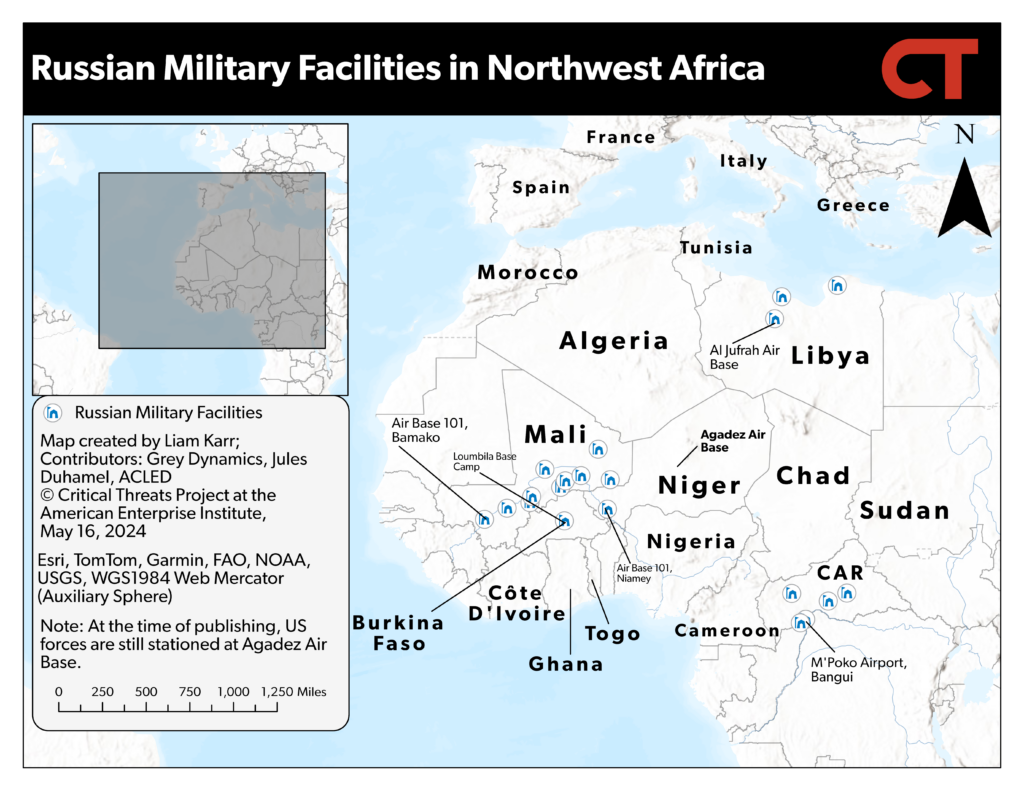

A Libyan port would also pose a long-term strategic threat to NATO by supporting Russia’s aim to have a standing force able to threaten NATO critical infrastructure with long-range cruise missile strikes from the sea.[25] Russian strategy and doctrine emphasize the importance of preemptive deployments of naval forces to establish deterrence and set favorable conditions for an ensuing conflict.[26] Russia identifies the navy as a critical tool to conventionally “attack critically important ground-based facilities” from the sea on short notice to destroy an enemy’s military and economic potential.[27] A Russian naval base at Tobruk would put most of central and southern Europe within range of Russian naval vessels with Kalibr cruise missile systems.[28]

Figure 2. Prospective Range of Russian Kalibr Cruise Missiles from Tobruk, Libya

Source: Liam Karr.

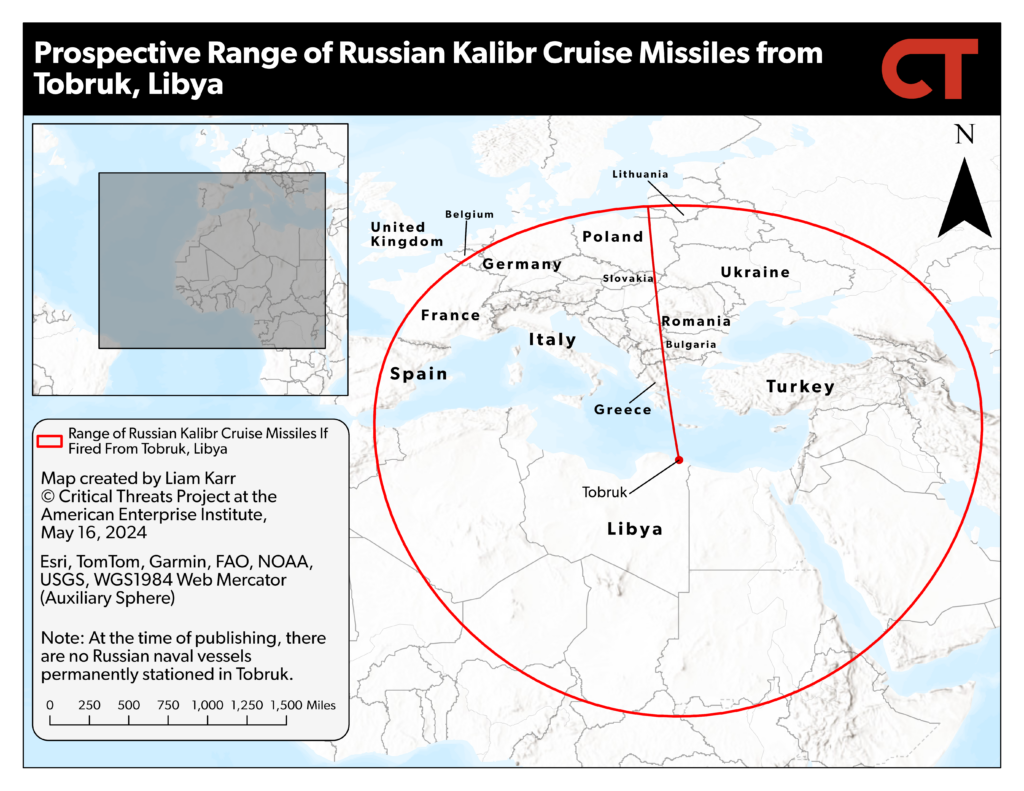

The Kremlin’s position in Libya also gives it the opportunity to destabilize Europe by weaponizing migrant flows from Africa, which it now has an even greater influence over thanks to its recent expansion along southern points of trans-Saharan migrant routes in the Sahel. The EU border patrol agency and numerous European officials have warned in 2024 that Russian President Putin is attempting to foment more refugee flows from Africa to destabilize Europe, influence elections, and undermine support for Ukraine.[29] Russia has repeatedly and systematically weaponized migrant crises in Europe. The Russian and Belarussian governments have flooded the borders of Finland, Lithuania, and Poland with refugees since 2021.[30] Their tactics have included luring refugees from the Middle East and Africa on flights to Europe based on false promises before dropping them at the border.[31] The Kremlin also foments prolonged instability in theaters where it is active, such as Libya, the Sahel, Syria, and Ukraine, which creates long-term refugee crises.[32]

Russia now has a military presence along many of the trans-Saharan migrant routes, which presents it with opportunities to facilitate mass migration. Russian mercenaries in the Sahel have contributed to a massive spike in human rights abuses since 2021, helping fuel record-high levels of trans-Saharan migration to Europe.[33] Russian forces are already active near nodes in the trans-Saharan routes in Mali, and CTP has assessed they will likely begin operating at key points in Niger after US forces withdraw in the coming months.[34] The EU border patrol agency noted that 380,000 migrants attempted to cross into Europe from Libya in 2023, the highest number of irregular crossings since 2016.[35]

Russia has already used its influence to at least indirectly support African allies that aim to increase migrant flows to Europe. Haftar has explicitly aided migrant smugglers in Libya by granting them security clearances.[36] Russia’s partners in the Nigerien junta annulled an EU-backed migration law that aimed to stem migrant flows in December 2023, benefiting both allies but directly increasing migrant flows to North Africa and Europe.[37]

Figure 3. Growing Russian Presence on Trans-Saharan Migration Routes in West Africa

Source: Liam Karr.

Russia has also used its presence in Libya to protect its oil and gas shares, constraining Western access and increasing Western dependence on Russian energy supplies. Europe has attempted to cut Russian energy purchases since Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022.[38] Russian military influence over Libyan oil fields has prevented the West from investing in Libyan oil as an alternative to Russian gas.[39] Libya has also increased its purchases of Russian gas by tenfold, helping mitigate this shortfall.[40] Libyan fuel smugglers then resell vast quantities of this Russian gas to Europe, further undermining European efforts to ban Russian gas imports.[41] Western and Libyan officials also claim that LNA leaders use their cut of the illicit funds that smuggling generates to fund Russian troop deployments.[42]

West Africa

Russia has recently expanded military cooperation with former Portuguese colonies in West Africa as it continues to expand its influence in Africa. Russia announced on May 5 that it had begun implementing a military cooperation deal with São Tomé and Príncipe that the countries signed in late April.[43] Sputnik reported that the agreement included cooperation on joint military exercises, visits from Russian military assets, education and training, recruitment, equipment, logistics, and planning.[44] Bissau-Guinean President Umaro Sissoco Embalo separately visited Russia for Victory Day celebrations from May 9 to 11. Embalo met with Putin and the head of the Chechen Republic, Ramzan Kadyrov, during his visit.[45] Russian media reported that Embalo agreed to send Bissau-Guinean troops for joint training exercises at the Russian University of Special Forces Chechnya during the visit.[46]

Russia had already increased economic cooperation with Guinea-Bissau since at least 2021.[47] Putin and Embalo met in Moscow in October 2022 when Embalo was the chair of the Economic Community of West African States—the West African economic bloc—and again in July 2023 when Embalo attended the 2023 Russia-Africa summit.[48] Putin highlighted the desire to increase bilateral trade and investment, specifically in mineral resource exploration and extraction, infrastructure, energy, and agriculture.[49] Bogdanov met with the Bissau-Guinean natural resources minister to further these discussions in February 2024.[50] Russia also forgave a $26 million debt from Guinea-Bissau in March 2024.[51] Duma Chairman Vyacheslav Volodin separately met with the national assembly speakers of Guinea-Bissau and São Tomé and Príncipe in March 2023 as part of the Second International Parliamentary Russia-Africa conference in Moscow.[52]

However, Guinea-Bissau has also maintained bilateral partnerships with pro-Western states since 2022, including Ukraine. Embalo was the first African head of state to visit Ukraine after the Russian invasion when he met with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy on the same trip he first met with Putin in October 2022.[53] Embalo had another phone call with Zelenskyy in July 2023.[54] The two leaders discussed bilateral cooperation during both discussions, especially on food security and rejecting Russian mercenary activity. Embalo has also established solid ties with France since 2022, which led to French commitments to fund education and economic development programs.[55]

Russia is likely trying to spread its influence from the landlocked Sahel and CAR into key waterways for regional and transatlantic shipping. The National Resistance Center of Ukraine, which is an information operation and partisan support organization run by Ukrainian special forces, claimed in February that the Kremlin was already trying to tighten its relationship with Togo to strengthen its logistics corridor from Libya, through the Sahel, and to the Atlantic.[56] Russian forces in the CAR heavily rely on the Cameroonian port at Douala to import and export goods and equipment.[57] Greater Russian presence in Guinea-Bissau or São Tomé and Príncipe could provide similar infrastructure for Russian imports and exports. Greater port access and military engagement in coastal West Africa would also enable Russia to expand its regional partnerships by cooperating with African states on issues such as illegal fishing, piracy, and oil exploration.

Figure 4. Russia Seeks Greater Atlantic Access in Africa: Russian Military Footprint in Africa

Source: Liam Karr.

The Kremlin may also seek to undercut African support for Ukraine as a secondary goal. Ukraine had discussed in 2023 using Portugal as a conduit to facilitate tighter relations with African countries as it looked to boost its support on the continent, since many African countries have been ambivalent about or supportive of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.[58] Russia increasing its partnerships with former Portuguese colonies, especially Guinea-Bissau, limits the impact of Ukraine’s outreach. CTP assessed in May 2024 that undermining the SAF’s relationship with the Kremlin was a secondary aim of increased outreach to the SAF in Sudan, underscoring this broader political tug-of-war across the continent.[59]

Russian Atlantic basing in West Africa is a potential but less direct alternative to Mediterranean basing to threaten NATO’s flank. Russia underscored its intention to project naval military power into the Atlantic throughout 2023 by increasing Atlantic submarine patrols and deploying an Admiral Gorshkov–class frigate to conduct a computer simulation hypersonic cruise missile strike exercise in January.[60] Russian nuclear-powered submarines based in the Atlantic would be past the main NATO checkpoint to the Atlantic at the British territory of Gibraltar, giving Russia easier access to the United States and NATO’s rear flank.[61] However, the increased Russian submarine patrols in 2023 highlight that the Kremlin does not need additional bases to pose this threat.[62] Russian naval vessels with Kalibr systems would have to go less than 500 miles into open water from the Bissau-Guinean port capital, Bissau, to be within strike range of Gibraltar.

Guinea-Bissau might be seeking greater security cooperation with Russia after Embalo claimed to survive a coup attempt in December 2023. Embalo accused the national guard of attempting a coup, leading to a shootout with Embalo’s presidential guard.[63] Embalo dissolved parliament after the attempt, which had only been in place for six months since the former president dissolved it in 2022.[64] National elections are scheduled for December 2024.[65] The Kremlin has previously sent military support to improve the regime security of threatened leaders.[66] For example, the Burkinabe junta leader sought to contract Russian forces after a thwarted coup attempt in September 2023, and the Russian soldiers that arrived in Burkina Faso in January primarily deal with regime security.[67]

Anti-colonial sentiment likely contributed to São Tomé and Príncipe seeking a partnership with Russia. São Tomé and Príncipe said it would demand reparations from Portugal on May 2, days after it signed its agreement with Russia but before either side announced the deal.[68] The Portuguese president had said on April 27 that Portugal should pay reparations to former colonies, which the Portuguese government quickly rejected.[69] Russia has capitalized on anti-French sentiment in former French colonies to establish a foothold in the central Sahel in West Africa. Russia has also used information operations and diplomatic rhetoric to present itself as a popular non-colonial alternative to the West.[70]

Iran

Iran is using defense engagement to pursue uranium access in Africa. French media reported that Iran and Niger have been negotiating since the end of 2023 for Niger to provide 300 tons of uranium yellowcake to Iran in exchange for drones and surface-to-air missiles.[71] The Wall Street Journal reported that the US told Nigerien officials during March meetings that any sale of uranium to Iran would lead to sanctions, which contributed to the junta annulling defense cooperation and eventually kicking out the over 600 US troops still stationed in the country.[72] The head of the Atomic Energy Organization of Iran denied the reports on May 15.[73]

Iran is also likely using defense engagement to pursue uranium or other minerals in Zimbabwe. Iran has increased outreach to Zimbabwe since April. Zimbabwean officials met with several high-level Iranian officials during various conferences, including Raisi, Iranian First Vice President Mohammad Mokhber, and Iranian Defense and Armed Forces Logistics Minister Brig. Gen. Mohammad Reza Gharaei Ashtiani in late April.[74] Ashtiani is responsible for managing the Iranian defense industry, arms procurement, and sales and expressed Iran’s readiness to increase cooperation with Zimbabwe during his meetings with Zimbabwean officials.[75] Zimbabwean officials also attended an international technology exhibition in Tehran, Iran, between May 7 and 10 that featured the Iranian Defense Industries Training and Research Institute, which is responsible for designing military equipment and systems.[76]

Iran likely seeks access to Zimbabwe’s unexplored uranium and other resource deposits. The World Nuclear Association reports that Zimbabwe has at least 1,800 tons of uranium and could have up to 25,000 tons.[77] The Zimbabwean government has been exploring its deposits for years but has not begun or contracted production.[78] An Australian firm has also discovered significant oil, helium, and hydrogen deposits in northern Zimbabwe since 2023, after signing a contract with the Zimbabwean government in 2018.[79] British media reported throughout the early 2010s that Zimbabwe had agreed to sell Iran uranium, which Zimbabwean officials denied; such sales never materialized.[80]

Raisi emphasized in 2022 that Iran aimed to grow cooperation with Zimbabwe in various sectors “including energy, mining, agriculture and technology.”[81] Iranian officials in charge of mining and energy have featured in discussions and signed agreements with Zimbabwe since 2023. The former Iranian mining minister met with their Zimbabwean counterpart in January 2023.[82] Iran and Zimbabwe signed a bilateral agreement to expand geological cooperation in all fields in February 2023, including exploration, mining, and training projects.[83] Iran and Zimbabwe signed 12 agreements, including an unspecified energy deal, when Raisi visited Zimbabwe in July 2023.[84] Iran’s industry, mining, and trade minister also attended the Iran-Africa summit that Zimbabwean officials attended in late April, although there were no reported meetings between the parties.[85]

Mozambique

ISMP conducted one of its largest and most complex attacks in years as it continues to operate at a scale unseen since at least 2022. At least 100 Islamic State Mozambique Province (ISMP) fighters launched a multipronged attack against Mozambican forces in Macomia town, the district head of Cabo Delgado Province’s Macomia district, in northern Mozambique on May 10.[86] Insurgents reportedly attacked Macomia from at least three directions and set up perimeter defenses to repel troops sent to reinforce security forces in the area.[87] Other groups of insurgents carried out complex ambushes on South African and Rwandan troops sent to reinforce the Mozambican forces, damaging and halting the convoys.[88] The attackers ultimately seized Macomia for 24 hours and killed around 20 soldiers, according to local sources, before retreating on May 11, after which civilians and security forces returned to the town.[89]

The Macomia attack is the latest instance of ISMP operating at a scale unseen since 2022. The group has launched attacks into parts of southern Cabo Delgado Province and across the Lurio River into Nampula Province, where it had been inactive since 2022.[90] The group also orchestrated another complex and large-scale attack involving 150 fighters in February that killed at least 20 Mozambican soldiers, which was the deadliest attack since 2021.[91] The group has also periodically occupied major coastal towns for days at a time for the first time since 2021, during which it engages in preaching activities and trade with local populations.[92] The International Organization for Migration estimates that ISMP’s resurgence has displaced over 110,000 people since December 2023, the second-largest wave of displacement in Cabo Delgado since the crisis began in 2017.[93]

Figure 5. ISMP Emerges Resurgent in Mozambique

Sources: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project.

The group is likely demonstrating its strength as regional security forces prepare to depart. The regional South African Development Community (SADC) security force in Mozambique began drawing down in December 2023 and is planning to withdraw by July 2024.[94] However, South Africa—which provides two-thirds of the 2,200-strong regional security force—agreed to keep its troops in the country until at least the end of 2024.[95] Tanzania is also keeping 300–500 soldiers in Mozambique to focus on border security as part of a bilateral agreement.[96] The EU has provided another $21.5 million to support Rwanda’s continued presence in Mozambique.[97] Rwandan officials have also said they will send more soldiers to Mozambique and increase their mobility to mitigate the loss of SADC forces.[98]

These security force arrangements are unstable and likely insufficient to degrade the ISMP insurgency. The South African and Tanzanian troops remaining in Mozambique have narrow aims that do not extend to significant counterinsurgency operations. South African officials said its troops are staying longer to better organize an orderly withdrawal at the end of the year, while Tanzanian forces are focused on securing the Mozambique-Tanzania border.[99] South Africa and Tanzania are also the primary troop contributors to an SADC mission that deployed to the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) in December 2023 to halt the escalating violence between Rwandan-backed rebels and Congolese forces, straining the logistical bandwidth and political will for a prolonged stay in Mozambique.[100]

Rwandan forces are the most effective and committed regional forces in Mozambique but suffer from competing objectives and an unclear future. Rwandan troops have succeeded in securing major towns and creating solid relations with local populations.[101] However, Rwandan forces are primarily concentrated around population centers and vital economic areas, which fails to project counterinsurgency pressure on insurgent support zones.[102] European countries also remain split on future financial support for Rwanda due to concerns over its human rights record and involvement with rebel forces in the DRC.[103] Rwanda’s efforts to fund, train, and equip rebel forces in the DRC also create the risk that it becomes preoccupied with that conflict.[104]

An escalation of the insurgency threatens to strengthen the global IS network and undermine local and international economic development. ISMP pools resources with IS’s other East African affiliates in the DRC and Somalia through the Al Karrar office, which has previously sent funds to IS Khorasan Province (ISKP)—IS’s main external attack node.[105] ISMP has never directly sent money to ISKP, but any surges in funding that would come with the group’s expansion would presumably become part of this regional pool that the regional IS office has previously sent to ISKP. IS central media has also increasingly covered ISMP governance activity to bolster IS’s global legitimacy and show it remains strong across the world.[106]

The insurgency may also derail international investment and stabilization efforts. The United States is directly involved in stabilization efforts and donated an additional $22 million in March 2024 to the $100 million it has already pledged to fund peace-building projects through the Global Fragility Act.[107] The current uptick in violence also undermines US-supported plans to restart liquefied natural gas projects that investors suspended due to the insurgency.[108] The projects represent a significant source of international investment that would boost the local and national economies, which would help address key economic drivers of the insurgency.[109] The projects would also produce significant quantities of gas that would help address the global gas squeeze that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and Europe’s efforts to shift away from Russian supply have exacerbated.[110]