Key Takeaways:

- Mali. Al Qaeda–affiliated militants recently conducted the first suicide vehicle-borne improvised explosive device (VBIED) attack in southern Mali since 2022, likely to support the group’s efforts to isolate a district capital nearly 175 miles north of the Malian capital. Al Qaeda’s Sahelian affiliate has rapidly strengthened in the region surrounding Bamako since the beginning of 2022 and will likely increase the rate and sophistication of its attacks farther south and amplify pressure around the Malian capital in the coming years.

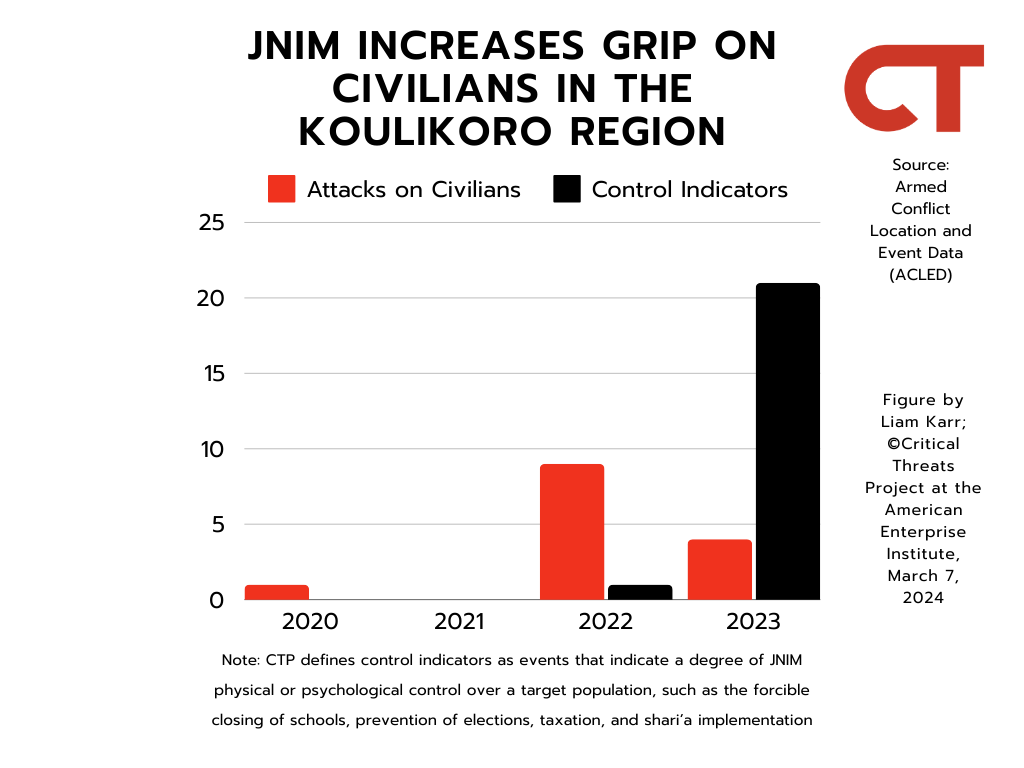

- Nigeria. The Nigerian and Russian foreign ministers met in Moscow on March 6 and outlined areas for increased bilateral cooperation and their states’ shared interests on issues such as the Israel-Hamas war. Nigeria likely will seek to expand its arms purchases from Russia during the coming years, strengthening this key area of preexisting cooperation. Nigeria’s recent criticism of Western military aid is similar to the grievances of their Burkinabe, Malian, and Nigerien neighbors, who have downgraded ties with the West in favor of Russia since 2021.

Assessments:

Mali

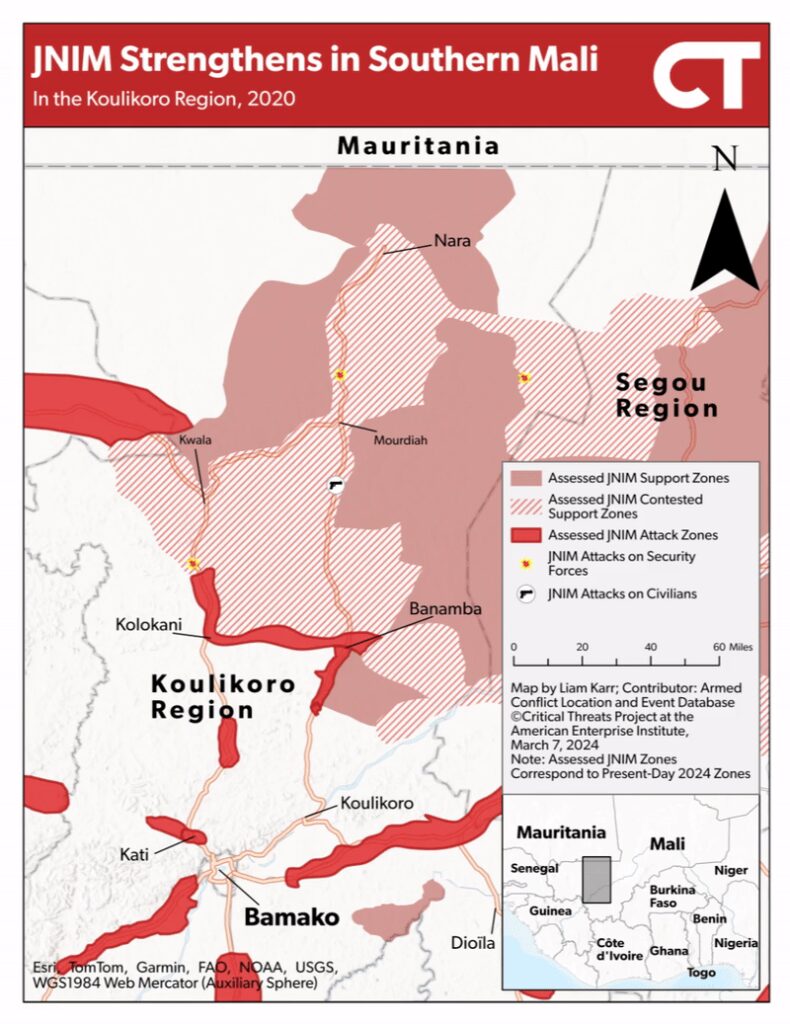

Al Qaeda’s Sahelian branch conducted its first VBIED attack in southern Mali since 2022, likely to support the group’s efforts to isolate a district capital near the border with Mauritania. Al Qaeda’s Sahelian affiliate, Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wa al Muslimeen (JNIM), conducted a large-scale complex attack targeting a Malian army base near Kwala, 100 miles north of Mali’s capital, on February 28.[1] JNIM militants commenced the attack with a suicide VBIED followed by approximately 100 attackers that stormed the Malian army position.[2] JNIM last used a suicide VBIED in southern Mali in July 2022.[3] The Malian army claimed that air and ground reinforcements forced the attackers to retreat north, where soldiers allegedly destroyed JNIM bases.[4] The JNIM attackers killed at least 30 Malian soldiers and looted military weapons, vehicles, and uniforms.[5]

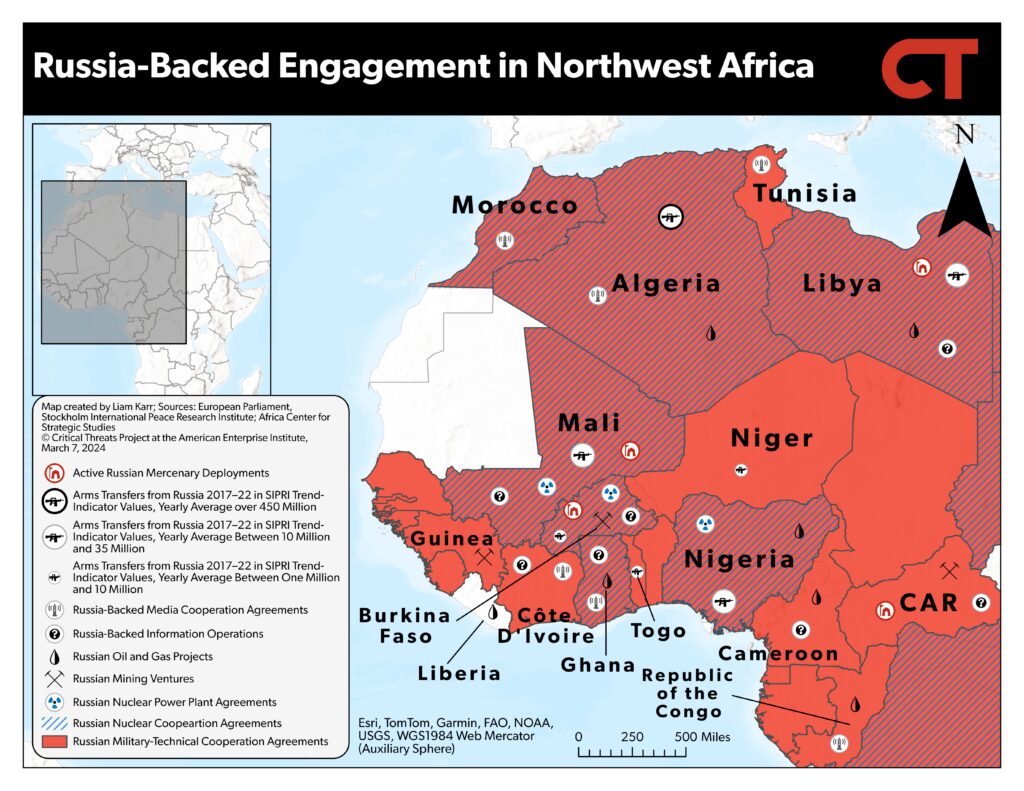

The attack is likely part of a JNIM campaign to degrade Malian lines of communication along the RN4 road that connects the district capital Nara to the rest of the region surrounding Mali’s capital, which has been ongoing since at least the last quarter of 2023. Nearly all JNIM’s attacks in the Koulikoro region have occurred along the various roadways surrounding Nara since it claimed to seize a Malian army–Wagner Group base along the RN4 at the beginning of October 2023.[6] All but two attacks in 2024 have occurred along the RN4.[7] The Armed Conflict Location and Event Database (ACLED) recorded that JNIM had already targeted Malian forces traveling between Kwala and Mourdiah—the midpoint town between Kwala and Nara—in a complex ambush involving a suicide motorcycle-borne improvised explosive device in December 2023.[8] The Malian armed forces in Kwala were stationed there to secure the RN4.[9]

Figure 1. JNIM Targets Nara and the RN4 in the Koulikoro Region, Southern Mali

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Database.

JNIM has gradually increased its attacks around Nara since the beginning of 2022 and may be setting conditions to besiege the town as it has other major population centers in the Sahel. JNIM began increasing its attacks around Nara in 2022, after establishing support zones to the east between 2018 and 2021.[10] The group has regularly besieged population centers in Mali and Burkina Faso instead of taking them by force.[11] JNIM conducts sieges to undermine state authority, control local traffic and economic activity, and punish civilians presumed to be cooperating with state security forces.[12] The psychological impact and humanitarian strain of a siege on civilians additionally gives the group greater leverage in negotiations with local leaders that can lead to agreements that give it an even greater degree of indirect control.[13] These consequences isolate security forces and degrade their ability to operate in the surrounding areas without significant risk, degrading the Malian government’s ability to control and contest JNIM outside of population centers.

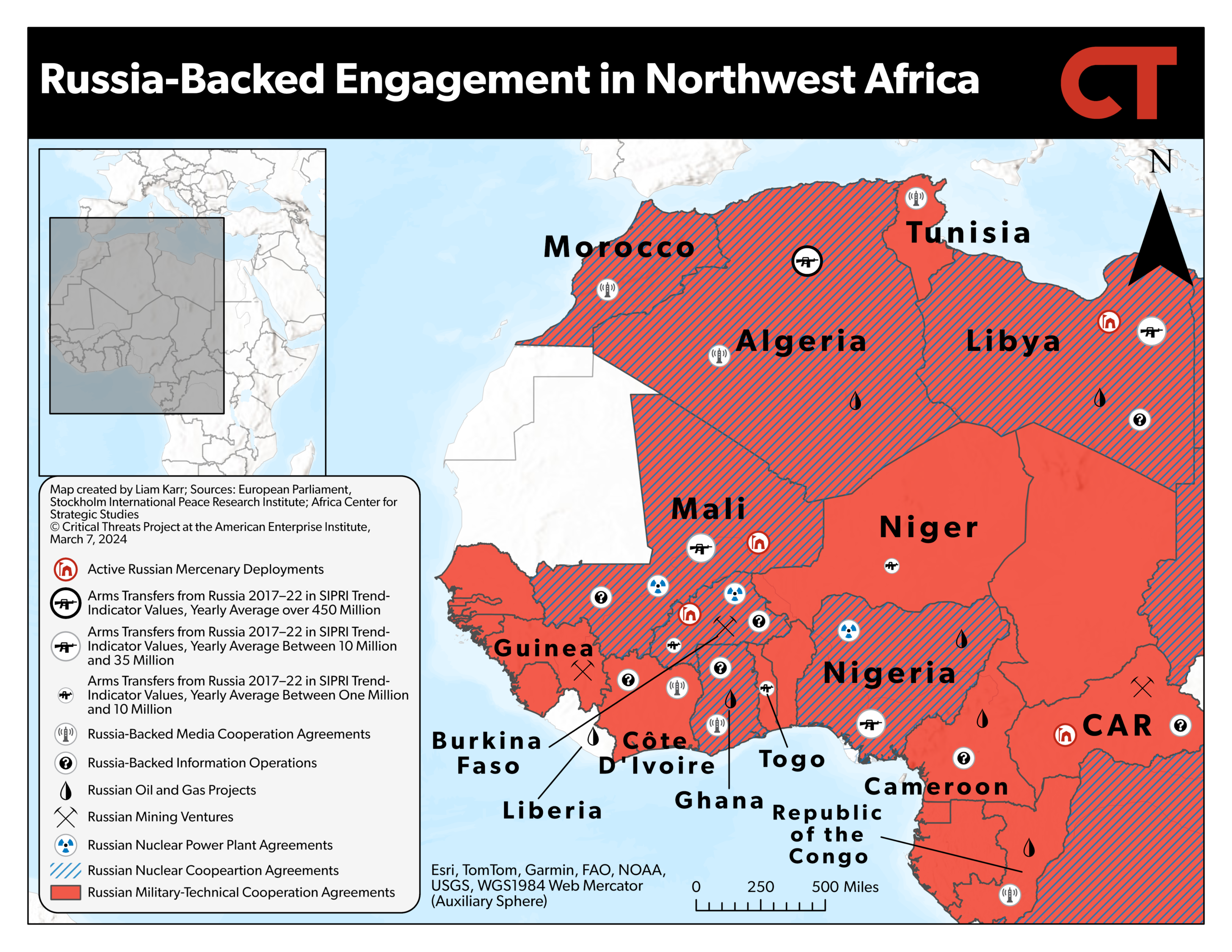

JNIM will likely increase the rate and sophistication of its attacks farther south and amplify pressure around the Malian capital in the coming years. JNIM has increased the rate, geographic spread, and sophistication of its activity throughout the Koulikoro region since the beginning of 2022.[14] The group only carried out a handful of attacks in northern Koulikoro through 2021, most of which targeted security forces.[15] However, it significantly increased the rate of coercive attacks on civilians in 2022.[16] ACLED recorded growing reports of control indicators in 2023, such as JNIM closing schools, preventing local elections, taxing civilians, and enforcing localized Shari’a agreements in Nara and Banamba districts (officially called cercles in Mali).[17] JNIM has also carried out its first two suicide VBIED attacks in the Koulikoro region since 2022.[18] These sustained trendlines demonstrate that JNIM is making strategic efforts to expand and increase its capabilities in southern Mali.

Figure 2. JNIM Increases Grip on Civilians in the Koulikoro Region

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Database.

JNIM likely has the capability to increasingly isolate district capitals south of Nara in the coming year as it is currently doing to Nara. ACLED recorded that the group has closed numerous schools, disrupted local elections, and taxed civilians around the district capital Banamba.[19] JNIM can use these support zones around Banamba town and along the RN4 to amplify pressure on the RN7, which links Nara and the RN4 to Banamba. The multiple instances of JNIM control activity in rural areas along the RN7 and the lack of JNIM attacks on the road since 2022 indicate that JNIM already exercises a degree of control over the passage.[20]

JNIM has also established support zones north of Kwala that it can use to pressure the RN3, which links Bamako and northwestern Mali via the district capital Kolokani town. JNIM militants that participated in the complex suicide VBIED attack on Kwala retreated north after the attack, indicating that JNIM is currently using the area to support attacks along the RN4.[21] Kwala lies at the intersection of the RN3 and RN4, meaning the group can attack the road if it chooses to. Stronger support zones around Nara and the RN4 would risk a “snowballing” effect down the RN3 by degrading security forces’ ability to pressure JNIM from bases like Kwala, thus strengthening JNIM’s support zones and freeing more resources that are currently focused on the RN4.

Figure 3. JNIM Strengthens in Southern Mali: In the Koulikoro Region, 2020–2023

Note: Static versions of each map from 2020 to 2023 can be found on the

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location and Event Database.

JNIM has increased the rate and sophistication of attacks on roadways around Bamako each year since 2022, demonstrating the intent and growing capability to attack near the capital.[22] JNIM waged an offensive targeting the roads surrounding Bamako in the first half of 2023, conducting at least 17 attacks within 70 miles of the capital between January and July.[23] CTP previously assessed that JNIM aimed to disrupt lines of communication in southern Mali and discredit the Malian junta based on JNIM primarily targeting security forces and framing the attacks as a challenge to the junta’s authority.[24] The group also launched a complex attack involving two suicide VBIEDs targeting military installations at Kati—10 miles from Bamako—in 2022, demonstrating its capability to carry out more sophisticated attacks around Bamako for the first time since 2015.[25]

JNIM strengthening its support zones farther south would boost its ability to target Bamako and its environs. JNIM’s lack of strong support zones in the districts around Bamako limits the group’s ability to sustain smaller-scale attacks, like the 2023 campaign, or regularly engineer sophisticated attacks, like the 2022 bombings.[26] However, strengthened support zones around Kolokani and Banamba would bring JNIM to the border of many of these districts and connecting roadways and create another “snowballing” risk. This expansion would once again degrade security forces’ ability to control and contest areas closer to the capital, significantly increasing the risk of JNIM support zones that are capable of housing improvised-explosive-device and VBIED manufacturing facilities and infantry staging grounds within range of Bamako and other critical infrastructure around the capital.

The Malian junta and its Wagner Group auxiliaries likely lack the capacity to increase their presence in southern Mali without making strategically significant sacrifices elsewhere, which would risk undermining the junta’s legitimacy. Already-stretched security forces backfilled over 13,000 UN peacekeepers who withdrew from central and northern Mali in 2023. These security forces resumed fighting with separatist rebels in northern Mali for the first time since 2015 to take back significant rebel-controlled towns over 700 miles from Bamako.[27] These additional operations have at least partially contributed to a decrease in counterterrorism operations in central Mali since mid-2023.[28]

The junta has rooted its political legitimacy in these efforts and others that seek to reclaim Malian “sovereignty” from external partners and internal threats.[29] In 2024, Russia has continued expanding the Wagner Group base in Bamako, which supports the roughly 2,000 mercenaries operating there.[30] However, the Kremlin still faces capacity limitations that would challenge a significant increase in mercenary deployments to Mali, as it tries to expand its mercenary presence across Africa while supporting its war in Ukraine.[31]

Nigeria

The Nigerian and Russian foreign ministers met in Moscow on March 6 and outlined areas for increased bilateral cooperation and their states’ shared interests on issues such as the Israel-Hamas war. Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov called Nigeria a “priority partner” in Africa and highlighted other desired areas of trade and military cooperation alongside Nigerian Foreign Minister Yusuf Tuggar in a post-meeting press conference.[32] Both ministers announced plans for a joint committee to hold further discussions and implement preexisting agreements.[33] Such agreements would include a 2017 deal with Russia’s State Atomic Energy Corporation, Rosatom, to construct nuclear power plants in Nigeria and a 2021 military-technical cooperation agreement for equipment supply, technology transfers, and personnel training.[34]

Lavrov also emphasized support for a cease-fire in Gaza and the need to start “real, rather than ostentatious work to create a Palestinian state in line with decisions taken by the Security Council and the UN General Assembly.”[35] Both Russia and Nigeria have called for a cease-fire in Gaza since October 2023.[36] Nigeria additionally hosted a Hamas delegation in February 2024.[37]

Nigeria likely will seek to expand its arms purchases from Russia in the coming years, strengthening this key area of preexisting cooperation. Nigeria was the second-largest importer of Russian arms in sub-Saharan Africa—narrowly trailing Mali—according to the most recent data from 2017 to 2022, from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute’s trend-indicator value (TIV) index.[38] The TIV measures the volume of military capability transfers rather than the financial value of arms transfers.[39] Russia has delivered at least 13 combat helicopters, two transport helicopters, and other matériel such as anti-tank missiles and aircraft engines since 2014.[40] This made Russia the second-largest supplier to Nigeria in terms of TIV, trailing China but ahead of the United States.[41]

Foreign arms transfers are supplying the overstretched Nigerian forces as they combat a multifaceted security crisis and secure a rapidly growing population of nearly 220 million people. Nigeria’s 223,000 military personnel are trying to combat a banditry-and-warlord crisis in the northwest, the long-standing Salafi-jihadi insurgency primarily concentrated in the northeast, a separatist insurgency in the southeast, and rising farmer-herder tensions across the country.[42]

Lavrov specifically noted after meeting with Tuggar that Russia will continue providing aid that increases the combat capabilities of national armies, security personnel, and law enforcement officers facing security challenges in the Sahara-Sahel region.[43] This would fit Russia’s already growing efforts to expand ties—and weapons transfers—with Nigeria’s junta-led neighbors Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger.[44] These sales help the Kremlin boost its economy, mitigate sanctions, and expand its influence to pose as a global power.[45]

Nigerian military officials have voiced frustrations with struggles to secure arms from Western partners, which will likely lead Nigeria to increase acquisitions from Russia. The Nigerian defense chief told reporters on February 20 that some countries refusing to sell Nigeria weapons due to human rights concerns have “double standards.”[46] The defense chief specifically cited the need for items such as helicopters, drones, and Mine-Resistant Ambush Protected vehicles.[47] US Secretary of State Antony Blinken said that the United States is working on growing equipment, technology, and weapons transfers to Nigeria when he visited on January 23 but provided no specific details of any new deals or agreements.[48]

US lawmakers have repeatedly paused large arms sales to Nigeria on human rights grounds.[49] Nigeria’s security forces have carried out numerous human rights abuses, such as extrajudicial killings, arbitrary arrests, incommunicado detention, sexual violence, and erroneous drone strikes.[50] Other US programs helping Nigeria’s neighbors have also sought to emphasize non-security approaches to adapt what US policy describes as “overly securitized” approaches.[51]

Nigeria’s recent criticism of Western military aid is similar to the grievances of their Burkinabe, Malian, and Nigerien neighbors, who have downgraded ties with the West in favor of Russia since 2021. The Sahelian juntas contend that Russia has given them greater access to the military hardware they need to defeat the Sahelian Salafi-jihadi insurgency than the West has.[52] The juntas used this argument to justify their decision to cut security ties with France and the West in favor of partnerships with Russia.[53] The Kremlin attaches fewer human rights requirements to its aid and is less concerned about security-force abuses, making it easier for countries facing democratic or humanitarian concerns to acquire weapons. These transfers have perpetuated further security-force abuses in the Sahelian countries, worsening their human rights records and further accelerating their break with the West.[54] Persistent human rights abuses unrelated to Russia have also strained US relationships with other key African partners, such as Ethiopia.[55]

Figure 4. Russia-Backed Engagement in Northwest Africa