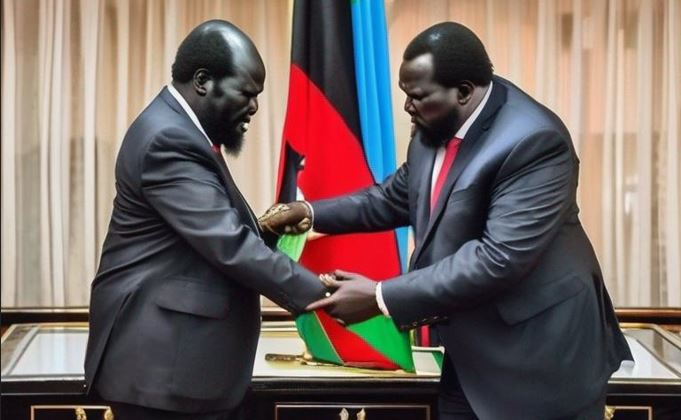

The political landscape in South Sudan is heating up as the two front-runners, Salva Kiir Mayardit and Riek Machar Teny Dhurgon, consolidate their power bases in Bahr-el-Ghazal and Upper Nile, respectively.

Should it take place, this election will be a historic milestone—the first national ballot vote since South Sudan’s secession from Sudan in 2011. This landmark event is eagerly anticipated by the increasingly impatient citizens of the country.

However, there are significant doubts about the feasibility, political intent, readiness, and wisdom of conducting an election next year in this conflict-ridden nation.

Key concerns among stakeholders and experts include whether the elections should proceed at all, the method of conducting them, and if the timing is appropriate considering South Sudan’s distinctive political and humanitarian circumstances.

Earlier this year, the incumbent president confirmed his intention to run for re-election during an event at a stadium in Bahr el Ghazal. He had previously accepted the endorsement of his party (SPLM) and assured that the elections would occur as scheduled.

For years, the issue of elections in South Sudan has been manipulated by political leaders, turning governance into a purely transactional affair. Rather than allowing citizens to scrutinize and elect their preferred leaders, politicians have employed a quid pro quo system, prioritizing their own interests and achieving their political goals through power-sharing agreements. Could 2024 be the year this damaging cycle is broken?

The necessary conditions

The pressure for South Sudan’s elections to proceed as scheduled is significant. The citizens are eager to participate in a well-organized election, but the question remains: does the country have the necessary infrastructure?

For a fair and credible election in South Sudan, three conditions must be met: electoral laws, voter registration with defined boundaries, and a safe civic space for voters. Unfortunately, these elements are currently lacking, casting doubt on the possibility of a credible election.

Support from both local (particularly the EAC) and international communities is robust, fueled by the hope that elections will end the conflict and steer the country towards a democratic state where political differences aren’t met with violent backlash.

The 2018 peace deal outlined several prerequisites for a credible election, including a permanent constitution. If elections take place next year, will they operate under the current constitution or a new one, which is still in draft form? This was flagged as an unrealistic expectation in the 2018 deal.

Public participation is crucial for formulating a constitution, which would require refugees and displaced persons to return home – a time-consuming process that the country cannot afford before December next year.

Even if a constitution is established before the election, it can’t be ratified by the handpicked members of the legislature – it must be approved by a duly elected parliament. Experts suggest using the amended transitional constitution of 2011, the Elections Act of 2102, or the 2018 RPA in the meantime.

Setting proper constituency boundaries and establishing a valid voter register requires a population census, again necessitating the return of refugees and displaced persons.

With ongoing inter-communal disputes and instability outside the capital, many refugees are reluctant to return. Previous constituency boundaries may need to be used for the elections, with population estimates based on demographic shifts if the elections proceed as planned.

Since its independence, South Sudan has been plagued by bouts of violence, creating unstable ground for an election. Should the elections be postponed until a more peaceful South Sudan emerges, or should the country proceed with the hope that this could be the key to lasting peace?

It’s a massive risk that might not yield the desired results, but what other options does the country have?

Fit to run?

Beyond the constitutional and legal challenges, there’s a significant issue that can’t be ignored. While it’s mostly hushed murmurs and subdued dissent due to potential repercussions, many believe that President Salva Kiir should not seek re-election in the upcoming polls.

The African model, where incumbent presidents cling to power indefinitely and manipulate or break laws that challenge their perpetual rule, is a familiar and frequently employed strategy.

Apart from his age, questions have been raised about the current president’s health and mental fitness to fulfill his duties as head of state.

Recent public mishaps, some resulting in extreme punitive measures for broadcasters and journalists in the country, highlight the pressing need for fresh leadership.

Protests are erupting across the continent as citizens resort to drastic measures to oust corrupt, inept ‘forever leaders’. Given its current economic condition, South Sudan cannot afford such upheaval. A coup, even just rumoured ones like a recent one reportedly thwarted, would undoubtedly cripple the nation.

The age of coalitions: The Kenyan model

As the election campaign intensifies and the two main contenders prepare for a fierce battle, analysts express doubts about positive outcomes, particularly in light of recent developments.

President Salva’s decision to venture into the territory of his long-time rival Riek Machar could be interpreted as a provocation, potentially igniting unrest now or in the run-up to next year’s election.

In an attempt to counterbalance the dominance of the ruling party, SPLM, various opposition factions are joining forces to form a coalition.

Drawing inspiration from Kenyan Opposition leader and former Prime Minister Raila Odinga, the coalition has even adopted a similar acronym, CORD (Coalition for Restoration of Democracy).

The new coalition comprises the Revive South Sudan Party led by Dr Ajak; Common People’s Alliance led by Garang Kuot Kuot; SPLM-IO Kitgwang represented by Goi Jooyul Yol; Steps We64 led by Suzzane Jambo; United Citizens for Change led by Jongkor Mayol, and the Red Army of South Sudan led by Deng Mayik Atem.

While those aligned with Vice President Riek Machar see this as a sign of emerging democracy in the country, the president’s camp dismisses the coalition as Western interference, hoping it will dissolve as quickly as it was formed.

In Conclusion

The overwhelming sentiment of the South Sudanese people is that elections should be held and soon. Some patterns however appear unchanging, especially with regard to tribal loyalties.

For example, a policy paper published in April of this year by Friedrich Stiftung shows that voters would still favour their kin to be in leadership positions even if they knew it was not the best decision for the country.

Elections, even if they do take place next year, will likely not alter the status quo and ethnic polarisation is likely to get to an all-time high with the election already being seen as a showdown between the Dinka and the Nuer; a total and erroneous disregard of the other tribes in the country.

If the Kenyan example is anything to go by, South Sudan needs to tread carefully; Countries that disregard the desire of the electorate to participate in free and fair elections, more often than not end up plunging into civic conflict.

The Luo-Kikuyu issue of Kenya was for a long time, especially before the historical handshake between former president Uhuru and former PM Raila Odinga.

The post-election violence incidences that Kenya, a much older country with more advanced electoral systems and a robust constitution, had to surmount speak to the type of calamity that would befall South Sudan were they to go through unrest.

Is South Sudan ready for polls in 2024? Yes. Will the election, if it takes place be able to stand up to scrutiny? Will it be free and fair? Will it foster peace and stability or simply stoke political and tribal conflict? Your guess is as good as mine but the hope is that transactional leadership comes to an end in the country.