In hindsight, it was inevitable that the charade of Nigeria’s regional leadership would end, but nobody could have predicted the dramatic way in which it happened.

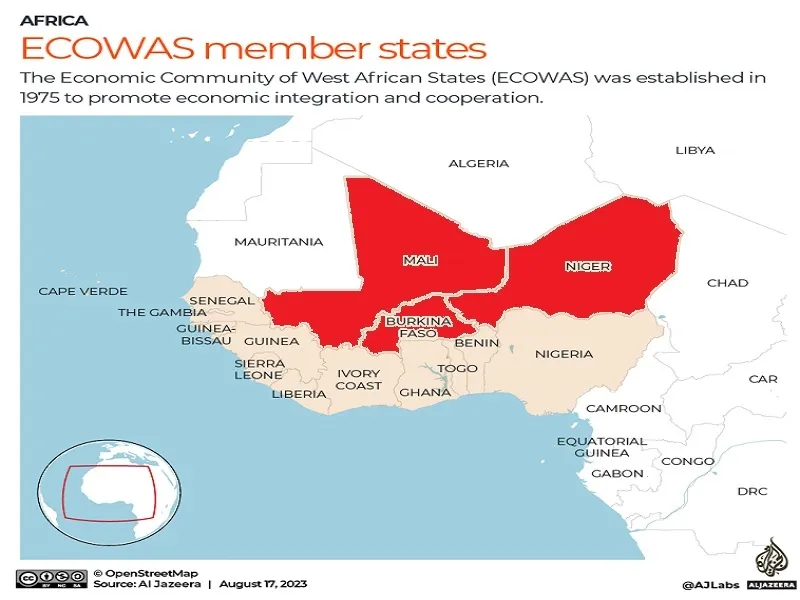

The planned Sahelian Confederation of Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger, which formed a military alliance last year, just announced in a joint statement that its members will all withdrawal from ECOWAS. They claimed that the bloc deviated from its founding mission of Pan-Africanism under foreign influence. They also condemned its sanctions policy and failure to thwart terrorist threats. All three were suspended before their withdrawal after each of them experienced patriotic military coups in recent years.

In geopolitical terms, this represents the defection of the bloc’s three landlocked members, all of whom moved much closer to Russia in the military sense since their respective leadership changes. All that remains are the coastal members apart from Guinea, which was also suspended after its own patriotic military coup but has yet to withdrawal and might now try to leverage its position for maximum benefit. None of this would have happened had it not been for Nigeria abusing its leading role in ECOWAS.

Africa’s most populous country has long envisaged becoming a continental leader, to which end it sought to utilize ECOWAS as a means of establishing its own “sphere of influence” over West Africa. This was expected to imbue its leadership with geopolitical benefits that could then be leveraged to make the case that Nigeria is indeed an emerging Great Power. The problem is that this policy wasn’t properly executed, with that country’s response to summer’s Nigerien patriotic military coup being its death knell.

For starters, Nigeria failed to equitably redistribute its enormous hydrocarbon wealth due to the incorrigible corruption of its state institutions, which exacerbated preexisting centrifugal processes between the majority-Muslim North and the majority-Christian South. This in turn contributed to the rise of UN-designated Boko Haram terrorists and various Southern separatists that Abuja considers terrorists. Nigeria’s domestic stability was understandably shaken by these developments.

Making everything worse, the Nigerian Armed Forces have been unable to fully defeat either of them, which harmed the country’s reputation. This can be attributable in part to the abovementioned incorrigible corruption that infects all state institutions. Nigeria’s traditional Western partners like the Anglo-American Axis turned a blind eye to these problems for pecuniary and strategic reasons related to fleecing its natural resources and keeping it under control respectively.

Nigeria was considered by them to be their West African gendarme that’ll lead regional military coalitions for intervening across ECOWAS anytime that Western geopolitical interests were seriously threatened. It was always supposed to remain impoverished, divided, militarily weak, and externally controlled via indirect means so that it couldn’t ever rise as the Great Power that its thought leaders had envisaged for decades. This state of affairs lasted up until summer’s Nigerien patriotic military coup.

The removal of Mohamed Bazoum, who initially promised to fight terrorists but ultimately allied with them to the chagrin of his armed forces, was the catalyst for dispelling the illusion of Nigeria’s regional leadership. The sequence of events that rapidly unfolded in the aftermath led to Nigeria threatening a military intervention aimed at reinstalling Bazoum and imposing crippling sanctions, the first of which didn’t materialize while the latter backfired by uniting average folks around the military authorities.

The devastating impact of the sanctions led to Nigeria losing the region’s hearts and minds in an instant since many across West Africa feared that they too might one day suffer due to larger political developments outside their control. The decision not to militarily intervene averted a lot of bloodshed, but it also made many believe that the Nigerian Armed Forces are just a paper tiger. Both soft power consequences combined to shatter the false perception of Nigeria’s regional leadership.

It’s beyond the scope of this analysis to explain why Nigeria called off its threatened intervention in Niger, but this analysis here argues that the US flexibly adapted to fast-moving developments to kick France out of that uranium-rich country while also keeping Russian influence there in check to an extent. Basically, Nigeria was set up to fail by the Anglo-American Axis’ de facto US leader, whose regional interests were advanced as best as possible given the circumstances but at the expense of Nigeria’s.

In hindsight, it was inevitable that the charade of Nigeria’s regional leadership would end, but nobody could have predicted the dramatic way in which it happened. Nigeria lost all the goodwill that it earlier earned by collectively punishing the Nigeriens and then made itself look weak by not following through on its threatened military intervention, which it shouldn’t have ever considered in the first place. These policy failures were due to it operating under foreign influence instead of pursuing national interests.

Nigeria could have reacted much more pragmatically to its northern neighbor’s unexpected leadership change by simply respecting that country’s sovereignty despite disagreeing with the course of its domestic political developments. Targeted sanctions could have signaled its disapproval alongside suspending it from ECOWAS but still retaining dialogue channels at certain levels. ECOWAS should have stayed true to its founding mission of regional integration, which was nothing but a ruse in retrospect.

The bloc just lost a large proportion of its total area and consequently limited itself to a coastal coalition of smaller-sized Nigerian-led states that are all indirectly under Anglo-American influence. This outcome could have been avoided in principle if only Nigeria decided to reform ECOWAS’ de facto function from being its joint patrons’ regional gendarme to truly pursuing multipolar integration. Its military-political leadership is so corrupt, however, that they remained blind to the crisis right in front of their eyes.

All told, it’s for the better that the illusion of Nigeria’s regional leadership was finally dispelled in such a dramatic way, and hopefully it’ll wake the aforesaid leadership up to the reality of what just happened. Now’s the time for them to liberate their country from foreign tutelage and make up for lost time by implementing comprehensive reforms so as to have a chance at one day becoming a Great Power. To be honest, there aren’t any indications that they’ll do this, but Africa would benefit if this ever happens.