Russia has pioneered a model of disinformation to gain political influence in Africa that is now being replicated by other actors across the continent.

Disinformation is the intentional dissemination of false information with the intent of advancing a political objective. Africa has been the increasingly frequent target of such campaigns. In recent years, dozens of carefully designed campaigns have pumped millions of intentionally false and misleading posts into Africa’s online social spaces. The ensuing confusion in deciphering fact from fiction has had a corrosive effect on social trust, critical thinking, and citizens’ ability to engage in politics fairly—the lifeblood of a functioning democracy.

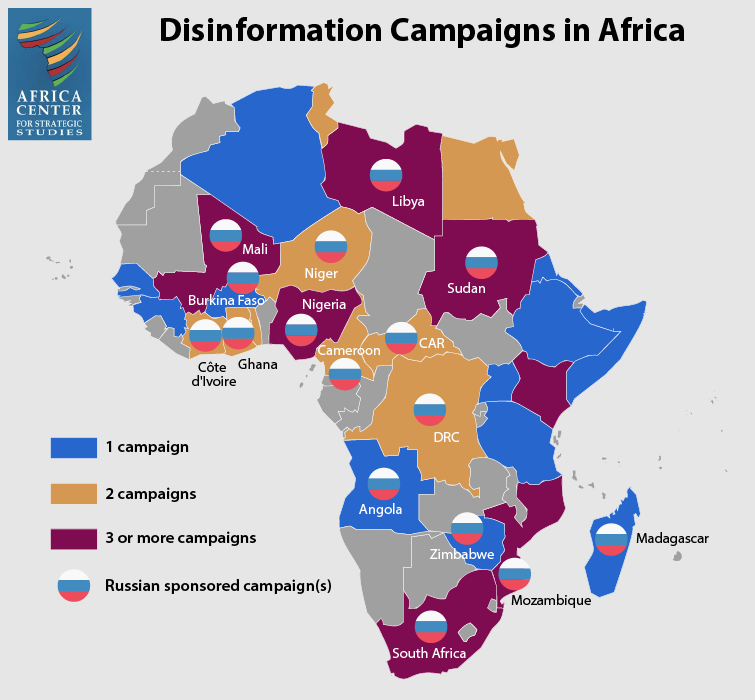

Russia has been the leading purveyor of disinformation campaigns in Africa with at least 16 known operations on the continent. Drawing on a legacy dating back to Joseph Stalin (who coined the term dezinformatsyia), the targeted tactics of disinformation in Africa are adapted from the Russian military strategy of “ambiguous warfare.” This strategy amplifies grievances and exploits divisions within a targeted society, fostering fragmentation and inaction—all while affording the perpetrators plausible deniability. The objective often is less to convince as to confuse citizens—thereby creating false equivalences between democratic and nondemocratic political actors, precipitating disillusion and apathy.

“Yevgeny Prigozhin, a Russian oligarch who leads the infamous Wagner Group mercenary force, has exported disinformation campaigns to every African country where Wagner has operated.”Russian disinformation campaigns are directed toward a political objective. These typically involve propping up an isolated African regime, which is then beholden to Moscow. Yevgeny Prigozhin, a Russian oligarch who leads the infamous Wagner Group mercenary force, has exported disinformation campaigns to every African country where Wagner has operated. In addition to promoting a favored regime and Russia’s role on the continent, the messages of these campaigns are antidemocratic, anti-West, and anti-UN.

Russian success in reaching a large African audience online with little overhead has inspired disinformation campaigns by other foreign governments. Domestic actors have adopted similar tactics for political ends in a growing number of African countries. Of the more than 50 documented disinformation campaigns on the continent, roughly 60 percent are externally driven, though these figures are inherently imprecise.

Over time, disinformation campaigns in Africa have become increasingly sophisticated in camouflaging their origins by outsourcing posting operations to local “franchised” influencers who are supplied content from a central source. These strategies are making it both harder to detect and to remove such insidious influence campaigns.

The identified disinformation campaigns are likely only a fraction of the total targeting the continent. According to Tessa Knight, a South Africa-based researcher with the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab, “Every time I have set out to search for coordinated disinformation in advance of an election or around conflicts, I have found it. I have not investigated an online space in Africa and not found disinformation. I think a lot of people are not aware of the scale of disinformation that is happening in Africa and how much it is distorting information networks.”

Removing Inauthentic Content Has Not Been a Priority

Social media sites have struggled to contain the impact of these networks and to take down their content before it is consumed and spread by targeted users.

Identifying increasingly sophisticated disinformation campaigns requires time and effort. However, when these campaigns are exposed in Africa, social media platforms have been reluctant to take sufficient action or to invest in the level of African content moderation required to curb disinformation in real time.

Facebook recently declined to remove coordinated networks operating in the Sahel, despite them having all the hallmarks of Russian disinformation, to the disappointment of social media researchers and watchdogs. This is part of a pattern of giving lower priority to removing inauthentic content in Africa. It also highlights that content moderation, fact-checking, and investigations into these campaigns in Africa are critical and need much more funding and greater African capacity building.

“Russian and other external and domestic actors are actively exploiting sites like Facebook, Twitter, Telegram, and TikTok to intentionally distort the information environment.”Allowing the network in the Sahel to remain active is also reflective of a larger disinclination on the part of social media companies to grapple with the fact that their algorithms accentuate inflammatory content. In response to claims by social media giants that they are trying to be neutral, analysts contend that allowing intentionally false content to be amplified on their platforms is itself a bias and contributes to actively shaping information systems in a way that is damaging for informed democratic discourse.

And more genuine democracy is something that a strong majority of Africans desire—poignantly seen by citizens in Sudan, Libya, Mali, Guinea, Chad, and Burkina Faso, among others, attempting to participate in their country’s political process despite risks of violence from military forces (many of which are backed by the foreign governments behind the disinformation campaigns).

Russian and other external and domestic actors are actively exploiting sites like Facebook, Twitter, Telegram, and TikTok to intentionally distort the information environment. Invariably, they are doing so to advance an antidemocratic objective. Disinformation, thus, is an effort to undercut popular sovereignty in Africa. Sowing distrust and undercutting truth is also inherently destabilizing—an outcome that will likely expand until there are heightened efforts to combat it.

Additional Resources

- Africa Check Fact-Checking Tips

- Jason Burke, “Facebook Struggles As Russia Steps Up Presence in Unstable West Africa,” Guardian, April 17, 2022.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Domestic Disinformation on the Rise in Africa,” Spotlight, October 6, 2021.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “A Light in Libya’s Fog of Disinformation,” Spotlight, October 9, 2020.

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Russian Disinformation Campaigns Target Africa: An Interview with Dr. Shelby Grossman,” Spotlight, February 18, 2020.

- Joseph Siegle, “Managing Volatility with the Expanded Access to Information in Fragile States,” in Shanthi Kalathil (ed), Development in the Information Age, (Washington: Georgetown University, 2013).

- Steven Livingston, “Africa’s Evolving Infosystems: A Pathway to Security and Stability,” Africa Center Research Paper No. 2, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, March 2011.