After the dramatic death of Russian warlord Yevgeny Prigozhin and several of his closest lieutenants in August, much of the discussion among international observers has centred around which individuals or organizations might take control of Prigozhin’s economic, military and criminal activities in Africa.

At the helm of the Wagner Group, Prigozhin established a complex business empire that spanned both licit and illicit economies, exchanging hired guns for access to natural resources in the African countries with whose governments he partnered. These resources, including gold and diamonds, are extracted through Wagner-controlled operations, secured by Wagner forces through often brutal means and smuggled overseas.1

Yet while Wagner, as it evolved under Prigozhin’s charismatic leadership, is unique in the scale and scope of its activities, it is not the only Russian actor in Africa operating in the mercenary space or ‘grey zone’. A range of different players are taking action to fill the void of Prigozhin’s leadership, including other Russia-based private military companies (PMCs), as well as Russian state officials and Wagner commanders who were not involved in August’s plane crash. Other Russian mercenary and criminal actors may also be making moves on the continent, as evidenced by the recent activities of former arms trafficker Viktor Bout, who is re-establishing himself as an economic and political player after having been freed from US prison in a 2022 prisoner swap.

While the current international focus on Wagner is understandable given the tumultuous recent events, understanding Russia’s influence overseas requires looking beyond Wagner to other PMCs, criminal networks and arms suppliers.

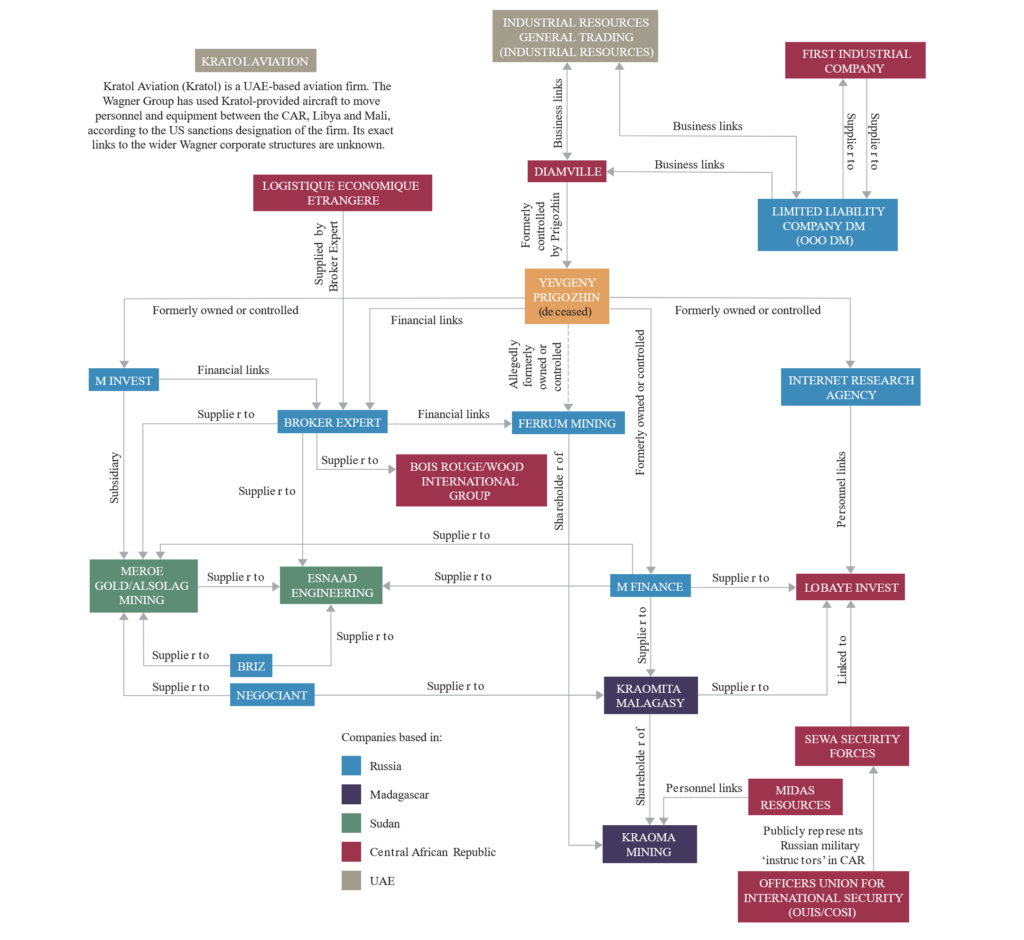

Figure 1 Wagner Group corporate structures relating to their activities in Africa.

Note: This graphic updates research first published in our February 2023 report ‘The grey zone: Russia’s military, mercenary and criminal engagement in Africa’. For more details on the companies involved, please refer to the original report.

Viktor Bout: a forerunner to Prigozhin

Before his arrest by the US Drug Enforcement Administration in 2008, Bout was arguably the most prolific arms trafficker of the post-Cold War era, earning himself the nickname the ‘Merchant of Death’.2 He ran a network of companies that were implicated in trafficking arms to 17 African countries – including Angola, Sierra Leone, Liberia and the Democratic Republic of Congo – as well as other countries such as Afghanistan.3 These businesses included freight companies and airlines that could ship Bout’s merchandise in exchange for access to natural resources.

In many ways, Bout can be seen as one of the forerunners of the Wagner Group’s strategy in Africa.4 Much like Prigozhin, Bout profiteered as a criminal entrepreneur, using a complex corporate network and offering Russian military assets in conflict zones to gain access to natural resources. He was the most prolific and high-profile of a number of prominent Russian criminal entrepreneurs who emerged in Africa from the remains of former Soviet military and intelligence institutions. At the time Bout was active in the late 1990s and early 2000s, many of the Russian criminal networks operating in southern Africa were ‘ex-securocrats who [had] gone private’, an officer from an elite unit of the South African police force told researchers in 2001.5

Investigators from the US who worked on tackling Bout’s network have argued that it was state-backed and state-facilitated. ‘It’s clear that he had significant ties to Russian government circles’, Lee Wolosky, a US official who led investigations into Bout’s network under the Clinton administration, told the Washington Post in 2022.6

Such arrangements are part of a broader pattern in which the Kremlin has reportedly used criminal actors to serve political ends overseas. ‘Russian-based organized crime groups in Europe have been used for a variety of purposes, including as sources of “black cash”, to launch cyber-attacks, to wield political influence, to traffic people and goods, and even to carry out targeted assassinations on behalf of the Kremlin,’ Mark Galeotti, a leading analyst of Russian organized crime, has said.7 The Wagner Group should be understood through the framework of this tendency to use criminal and grey zone private actors for political gain.

Bout’s modern day political and economic career

Now returned to Russia, Bout once again has an active career. He has made a start in politics, winning a seat in the regional assembly of Ulyanovsk in September 2023 as part of an ultra-nationalist party.8 During his campaign, Bout publicly demonstrated his links to the Wagner Group. He was joined on the campaign trail by Yevgeny Prigozhin in early June, just days before the ill-fated Wagner mutiny. According to local reports, Bout and Prigozhin visited weapons factories and developed plans for modernizing the military industry in Ulyanovsk,9 which is a ‘special economic zone’ within Russia.

Assisting on Bout’s campaign was Maxim Shugalei, a Russian sociologist and long-time ally of Prigozhin. Shugalei heads the Foundation for National Values Protection (FZNC) think tank. He has been backed by and worked on behalf of Prigozhin in Libya, Mali and the Central African Republic (CAR), promoting pro-Russian narratives and disinformation.10 After being held hostage in Libya, Shugalei also became the hero of a series of action movies that heroized Wagner’s exploits in Africa and were promoted heavily by the FZNC, among others.11

Prigozhin himself compared Bout with Shugalei in December 2022: when Bout was released by the US, Prigozhin described him glowingly as an ‘ideal of unshakeableness’ and as ‘Shugalei squared’.12

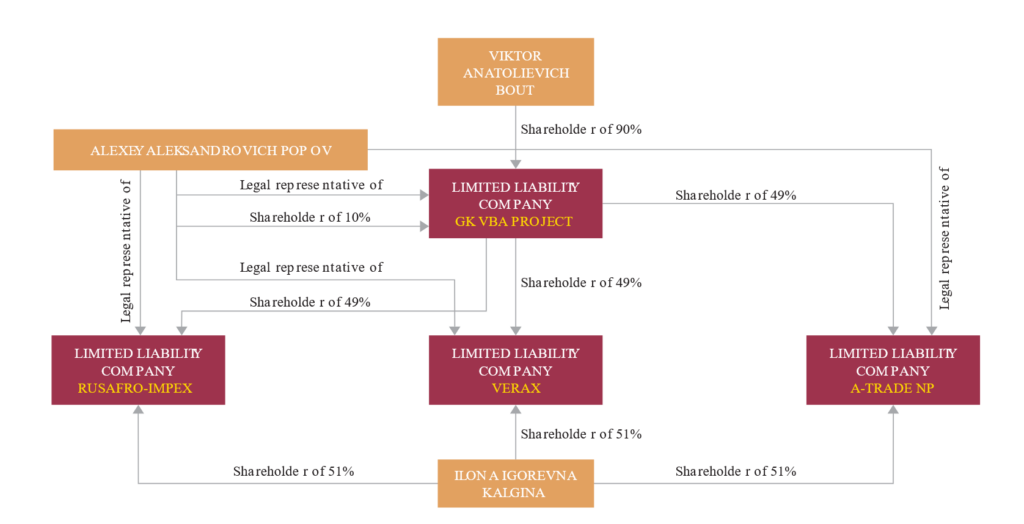

Bout has also developed a new business portfolio. He holds 90% of the newly registered company GK VBA Project, according to Russian corporate databases. GK VBA Project, in turn, holds a 49% stake in three other companies: A-Trade NP, Verax and RusAfro-Impex. The listed purposes of these companies include the wholesale trade of natural gas, fuel, machinery, equipment, food, beverages and tobacco products.13

Bout remains under US sanctions on the basis of his historical criminality.14 Since the mid-1990s, Western states have increasingly used targeted sanctions as a foreign-policy tool to counter transnational organized crime, often focusing on the relationships between criminal and conflict actors.15 Such was the case with Bout, who was originally sanctioned – alongside 30 linked companies and four individuals – due to his connections with former Liberian President Charles Ghankay Taylor.16

Under US sanctions rules, any entity owned 50% or more by a sanctioned individual is deemed ‘blocked’,17 meaning that the companies listed – of which Bout’s VBA Project owns only 49% – may still be able to operate through the international financial system with no barriers from the US. There is no information yet available as to where these companies are trading, nor is there any evidence to suggest that these companies have engaged in the illegal activity for which Bout became notorious.

Figure 2 Network of newly registered companies linked to Russian arms trafficker Viktor Bout.

However, Shugalei may have provided some clues as to what these companies will be doing. In updates posted to his Telegram channel, Shugalei has reported on discussing plans with Bout to export military utility vehicles and aircraft to Africa.18 Both of these are produced at factories in Ulyanovsk, Bout’s new political homeland, and RusAfro-Impex, the name of one of VBA Project’s subsidiary companies, could plausibly stand for ‘Russia-Africa Import-Export’.

Bout downplayed the possibility that he might once again develop a business portfolio in Africa in an interview with the New York Times in September 2023: ‘He [Bout] added that he had “nothing much left of any old contacts,” especially in Africa, where “the regimes are changing quicker than the weather sometimes”’.19 Yet in an interview with South African outlet DefenceWeb a month earlier, Bout told a very different story, claiming he would like to ‘apply his expertise’ to developing Russian economic cooperation with Africa and saying that he had founded new companies for this purpose.20 It appears that Bout is shaping his narrative to his audience, downplaying his business plans to a flagship newspaper from the country that hunted and jailed him for years.

Other Russian PMCs following the Wagner ‘blueprint’

Bout, Prigozhin and Wagner can be seen as part of a broader pattern in the way that the Russian state has backed and co-opted illicit and grey zone entrepreneurs. In the same way, some of the other Russian PMCs that may be poised to muscle in on Wagner’s operations in Africa follow the same blueprint and model.

Russian commentators with close ties to Wagner have referred, in the aftermath of Prigozhin’s death, to a possible ‘raider takeover’ of Wagner assets by other Russian PMCs. Two PMCs that may be orienting themselves to usurp Wagner’s role in Africa are Convoy and Redut. Both of these organizations have parallels to Wagner, as they are backed by prominent Putin-allied businessmen (as, until recently, Prigozhin was) and have links to Russian intelligence. Additionally, both organizations are led by former Wagner commanders.

Convoy is reportedly financially backed by Arkady Rotenberg, a close associate of Putin,21 and is led by Konstantin Pikalov, known by the call-sign ‘Mazai’, who was a Wagner commander in CAR when the three Russian journalists investigating the group were murdered.22 Pikalov was also prominent in Wagner’s operations to disrupt the 2018 presidential election in Madagascar.23 In late August, Convoy began advertising on Telegram to recruit pilots for African operations. An investigator for Russian media outlet iStories went undercover and spoke to a Convoy recruiter, who confirmed that recruits would be deployed in Africa.24

Redut, in turn, is led by Antoli Karazi,25 allegedly a former head of Wagner intelligence. Set up to protect the assets of prominent businessman Gennady Timchenko (Redut’s financier), and reportedly backed by Russian military intelligence,26 Redut has also reportedly become more active in recruitment for operations in Africa since the Wagner mutiny in June.27

Of course, Wagner and its associated networks remain active, and some leading Wagner figures who were closely allied to Prigozhin remain in post. For example, Dmitri Sytii, the longstanding frontman for Wagner’s political and (legally dubious) economic operations in CAR, continues to work from a former presidential residence in Bangui, according to reporting from the Wall Street Journal.28 Alexander Ivanov, head of a front company for Wagner’s operations in CAR – the Officers Union for International Security – likewise remains in post.29

Looking ahead: Russian military and proxy engagement in Africa

As demonstrated by Bout’s apparent positioning for providing military equipment to Africa, the Wagner Group is not the only agent of Russian influence in the mercenary grey zone. Other Russian PMCs and extant Wagner networks are also making their moves towards Africa. And when one scratches beneath the surface, there are links between Bout, Prigozhin, Wagner and the other Russian PMCs.

These private actors and proxies – including criminal actors – can be seen as part of a broader military–business complex through which Russia seeks to influence events overseas. Even with Prigozhin gone, the strategic goals of the Kremlin in furthering its interests, displacing the influence of Western nations, and extracting resources appear unchanged.

Notes

Julia Stanyard, Thierry Vircoulon and Julian Rademeyer, The grey zone: Russia’s military, mercenary and criminal engagement in Africa, GI-TOC, February 2023, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/russia-in-africa/. ↩

BBC News, Viktor Bout: Who is the ‘Merchant of Death’?, 18 December 2022, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-11036569. ↩

Guy Lamb, Viktor Bout: The southern African saga, Institute for Security Studies, 4 November 2011, https://issafrica.org/iss-today/who-is-viktor-bout. ↩

Julia Stanyard, Thierry Vircoulon and Julian Rademeyer, The grey zone: Russia’s military, mercenary and criminal engagement in Africa, GI-TOC, February 2023, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/russia-in-africa/. ↩

Jenni Irish and Kevin Qobosheane, South Africa, Penetrating state and business: Organized crime in southern Africa, 2, 71–135, Institute for Security Studies, 1 October 2003, https://issafrica.s3.amazonaws.com/site/uploads/Mono89.pdf. ↩

Adam Taylor and Claire Parker, Russia wanted Viktor Bout back, badly. The question is: Why?, The Washington Post, 8 December 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/07/29/victor-bout-gru-sechin/. ↩

Mark Galeotti, Crimintern: How the Kremlin uses Russia’s criminal networks in Europe, European Council on Foreign Relations, April 2017, https://ecfr.eu/wp-content/uploads/ECFR208_-_CRIMINTERM_-_HOW_RUSSIAN_ORGANISED_\CRIME_OPERATES_IN_EUROPE02.pdf. ↩

Valerie Hopkins, Russia’s ‘Merchant of Death’ is looking to forge a new life in politics, The New York Times, 10 September 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/10/world/europe/russia-bout-arms-dealing-politics/html. ↩

Report shared to a Wagner-linked Telegram channel, 13 September 2023, https://t.me/voenkor_rusvesnaa/6680. ↩

For a full profile of Shugalei, see Julia Stanyard, Thierry Vircoulon and Julian Rademeyer, The grey zone: Russia’s military, mercenary and criminal engagement in Africa, GI-TOC, February 2023, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/russia-in-africa/. ↩

The official trailer for the Shugalei film, translated into English, is available here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xGIj-C0hx-U. ↩

Statement released via the Telegram channel of Concord, Prigozhin’s company that acted as his public platform, 12 December 2022, https://t.me/concordgroup_official/126. ↩

Information collected through the SPARK Interfax database. ↩

Information available via OFAC Sanctions List Search: https://sanctionssearch.ofac.treas.gov/Details.aspx?id=8279. ↩

Matt Herbert and Lucia Bird Ruiz-Benitez de Lugo, Convergenze zone: The evolution of targeted sanctions usage against organized cime, GI-TOC, September 2023, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/sanctions-organized-crime/. ↩

US Department of the Treasury, Treasury designates Viktor Bout’s international arms trafficking network, 26 April 2005, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/js2406. ↩

Office of Foreign Assets Control, Entities owned by blocked persons (50% rule), https://ofac.treasury.gov/faqs/topic/1521#:~:text=According%20to%20OFAC%27s%2050%20Percent,one%20or

%20more%20blocked%20persons. ↩

Information shared by Maxim Shugalei to his Telegram channel, 31 July and 5 August 2023, https://t.me/max_shugaley/785, https://t.me/max_shugaley/790. ↩

Valerie Hopkins, Russia’s ‘Merchant of Death’ is looking to forge a new life in politics, The New York Times, 10 September 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/10/world/europe/russia-bout-arms-dealing-politics/html. ↩

Brett MacDonald, Exclusive: Viktor Bout still has his eye on Africa, DefenceWeb, 22 August 2023, https://www.defenceweb.co.za/featured/exclusive-viktor-bout-still-has-his-eye-on-africa/. ↩

Dossier Center, Cossacks, elf and Arkady Rotenberg – How the Convoy PMC works and who finances it, 14 August 2023, https://dossier.center/konvoy/. ↩

Roland Oliphant, Inside ambitious mercenary outfit Redut, the Wagner rival linked to the Russian spy services, The Telegraph, 24 August 2023, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/world-news/2023/08/24/redut-russia-yevgeny-prigozhin-plane-crash-rival/. ↩

The Insider, Mazai is Africa’s Wagner. Who runs Prigozhin’s business on the Black Continent, 14 August 2020, https://theins.ru/en/politics/253779. ↩

iStories, Накануне гибели Пригожина Минобороны начало набор бойцов в Африку через свои ЧВК, выяснили «Важные истории», 23 August 2023, https://storage.googleapis.com/istories/news/2023/08/23/nakanune-gibeli-prigozhina-minoboroni-nachalo-nabor-boitsov-v-afriku-cherez-svoi-chvk-viyasnili-vazhnie-istorii/index.html. ↩

The Insider, Best of enemies: Wagner chief Prigozhin’s feud with defense minister to blow up in his face, 12 May 2023, https://theins.ru/en/politics/261697. ↩

United Kingdom House of Commons Foreign Affairs Select Committee, Guns for gold: The Wagner network exposed, July 2023, https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/41073/documents/200048/default/. ↩

Rob Hastings, Wagner mercenaries could be absorbed by arch rival Redut and slip into the shadows after Prigozhin’s death, 26 August 2023, https://inews.co.uk/news/world/wagner-mercenaries-rival-redut-prigozhin-death-2573376; AP News, Russia’s Wagner mercenaries face uncertainty after the presumed death of their leader in plane crash, 26 August 2023, https://apnews.com/article/russia-putin-prigozhin-wagner-africa-belarus-e37f03e7fbb6baf36af0d4fb345deabe. ↩

Benoit Faucon, The elusive figure running Wagner’s embattled empire of gold and diamonds, Wall Street Journal, 21 September 2023, https://www.wsj.com/world/africa/wagner-africa-sytii-prigozhin-gold-12a45769?st=4rqy45ocfhw2f0t. ↩

Ivanov continues to make public statements criticizing Russian political leadership for ‘sabotaging’ Prigozhin’s achievements making inroads for Russia in Africa in tones that echo the diatribes Prigozhin himself used to post to Telegram in the months before his death. See, for example, this message shared to the COSI telegram channel, 22 September 2023, https://t.me/officersunion/473. ↩