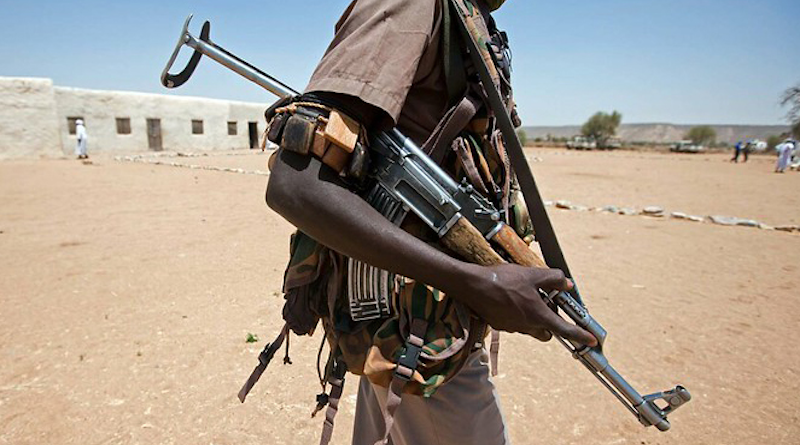

Child soldiers are being recruited by both sides in Sudan’s ongoing civil war, a cruel practice that threatens to destroy the fabric of the country.

Sudan’s capital, Khartoum, is now a war zone where child soldiers are actors in a nightmarish script. Recent clashes between the Rapid Support Forces and El-Shajara Armored Corps have exposed the horrors Sudanese children must endure, with witnesses reporting instances of child soldiers fighting on both sides.

The scope of child soldier recruitment in Sudan is alarming. Stories from across various regions reveal a systematic pattern of exploitation transcending both tribal lines and political affiliations.

The two main warring factions in the country, the Sudanese Armed Forces and the RSF are implicated. Witness testimonies depict a disturbing narrative of coercion, fear, and manipulation, in which children are often forced into combat against their will or lured with promises of material or monetary gain.

“The root causes of child soldier recruitment in Sudan are multifaceted,” Ahmed Gouja, a journalist from the town of Nyala in Sudan’s war-ravaged Darfur region, told Arab News.

Severe and widespread poverty has driven many children into the arms of the militias.

“Young people, often lacking access to basic necessities like food and a promising future, find themselves drawn to armed groups as a means of survival,” Gouja said.

Gouja personally knows many young men in Nyala who have joined the RSF. Two of his cousins have already joined the paramilitary group’s ranks; both are under 18, and neither has even completed their primary education.

The Darfur Bar Association is sounding the alarm about increasing child soldier recruitment in the war-ravaged African country. They explained that the RSF lures recruits using a combination of “money” and “false promises.” The paramilitaries have recruited children as young as 14 using these tactics.

“Such actions are considered war crimes, irrespective of whether conflicts are international or non-international,” the organization said in a recent statement.

According to the UN International Children’s Emergency Fund, over one million children have been displaced by the fighting in recent months. Worse still, hundreds have lost their lives and thousands more suffered injuries.

There have also been reports of children’s bodies in mass graves and of sexual violence perpetrated against young girls.

The conflict has not spared civilian areas. Schools remain closed, children’s institutions have come under attack, and even vital healthcare facilities are subjected to looting and destruction. These dire circumstances make it harder for humanitarian agencies to provide much-needed aid to Sudan’s embattled civilian population.

The situation in El-Shajara is demonstrative of the mortal wound this conflict has afflicted upon Sudan. The name once belonged to a peaceful area along the White Nile in southwest Khartoum.

Since the onset of this conflict, however, El-Shajara is now associated with violence and despair. As warplanes soar overhead and explosions shatter the air, the echoes of a once-thriving neighborhood are drowned out by the cacophony of battle.

El-Shajara’s surreal transformation in the space of mere months serves as a grim testament to how conflict can rewrite the very geography of a nation.

The cynical and widespread use of child soldiers in this conflict will also have a negative and lasting impact on the African nation’s societal norms and values long after the guns eventually fall silent.

Experts explained to Arab News how manipulating children and exploiting their innocence to transform them into instruments of destruction is not merely a cynical war tactic, but a strategic assault on the very fabric of society.

“Child soldiers are used to break down societal trust relations, as the whole idea of children becoming actors of killing, pillage, and destruction affects public psychology in a particular way that is much deeper and impactful,” Alpaslan Ozerdem, dean of the Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter School for Peace and Conflict Resolution, told Arab News.

“Conflict parties tend to see child soldiers as dispensable and force them to act in some of the cruelest aspects of their violence, as they tend to carry out orders without question,” Ozerdem said.

He added that children can also infiltrate communities without raising much suspicion, which can also influence some of the violent strategies employed in such environments.

For Gouja, the journalist from Nyala, “the recruitment isn’t driven primarily by tribalism as one might expect, but rather by the education system’s influence and the ideological mindset present in the country.”

He also stressed that “tackling poverty is crucial; and offering better prospects for a future outside armed groups can weaken their appeal.”

Nevertheless, other observers maintain that tribal pride plays a vital role in the Sudan conflict, with children coerced into joining armed groups to prove their machismo.

Over time, these children develop deep loyalties for their commanders and undergo profound psychological manipulation. The socialization processes that unfold after induction become the adhesive binding these fragmented lives into a cohesive group.

The harrowing truth is that psycho-social assistance is often a distant prospect for these child soldiers. Even when integrated into formal reintegration processes, access to such help remains limited.

More troublingly, these children are unlikely to opt for psychological support when offered, given the false perception that such help is an affront to the very masculinity they are being forced to adopt and prove.

“Central to the discourse of child soldier reintegration is the delicate balance between recognizing their agency and avoiding the pitfalls of infantilization or demonization,” Ozerdem said.

In his view, the pendulum swings between perceiving these children as vulnerable and powerless and deserving of protection to fearing their potential for violence and harm, thus viewing them as a threat.

“This dichotomy shapes reintegration policies, often casting them either as passive victims or imminent threats,” Ozerdem added.

Most importantly, these dire circumstances are often exploited to create a narrative that paints these conflict zones as places where the very essence of humanity is lost.

“This narrative further perpetuates a divisive dichotomy, pitting the image of ‘uncivilized locals’ against the perception of benevolent ’guardian angels’ from the West,” Ozerdem said.

“This framing not only oversimplifies the complex dynamics of these conflicts but also amplifies a sense of urgency within the international community to justify their military interventions.”

More generally, the use of child soldiers in armed conflicts is a distressing phenomenon that continues to haunt regions plagued by disorder and unrest.

The cruel practice has gained alarming traction in Africa, in particular. From the Central African Republic to Nigeria, the presence of child soldiers is a tragic constant in the continent’s many conflicts.

The continent, particularly Sudan, has been a focal point for this disturbing trend, leaving scars not only on the young lives entangled in the chaos and conflict but even on the collective conscience of the world.