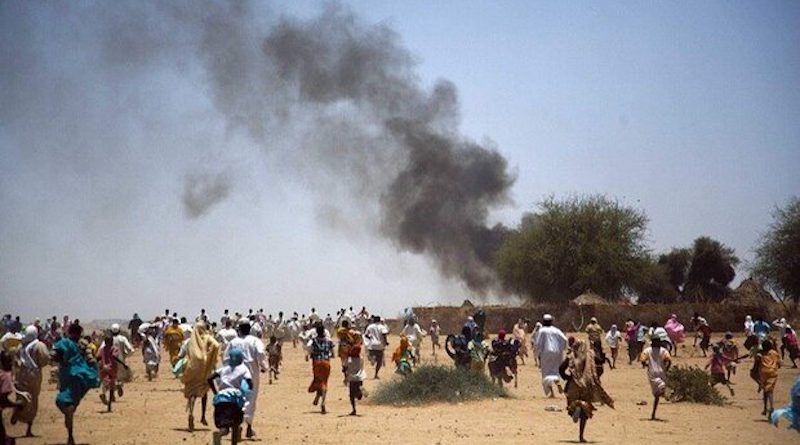

Violence broke out in Khartoum in the early morning hours of April 15. Over 100 days later, brutal fighting continues. Sudan’s bustling capital was awakened by violent clashes throughout the city targeting the government’s command and control centers. During the last nights of Ramadan, the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), a government-sponsored paramilitary force, began attacking the leadership of the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF).

Fighting between both parties is ongoing despite numerous short-lived cease-fires, and Khartoum has become a hotly contested warzone. As of July 21, 2023, according to the United Nations High Commission for Refugees, more than 3.3 million people have been displaced from their homes since the fighting began in April. Of those displaced by the recent fighting 738,000 have fled to neighboring countries, particularly Chad and South Sudan, while 2.2 million people have become internally displaced. Meanwhile, casualties are believed to number in the thousands in Khartoum State alone, the most populous state in Sudan, but we lack reliable tallies. As of July 5, the Sudanese health ministry estimates civilian deaths to be at 1,136, but according to Reuters that is likely a severe underestimate.

Many observers of Sudanese politics had long feared that a violent conflict would break out within Sudan’s security services. There have been thirty-five coup attempts in modern Sudan’s history. Therefore, the possibility of violence between parts of Sudan’s sprawling security apparatus was never remote. Yet, in recent years the tension between Sudan’s two principal military commanders has been particularly apparent, especially since the RSF began securing strategic positions in Khartoum, along with the SAF.

The two principal military commanders were Abdul Fattah al-Burhan, the leader of the SAF, and Mohammad Hamdan Daglo (Hemedti), commander of the RSF. Both took part in the palace coup on April 11, 2019, that removed their predecessor Omar El-Bashir from power. Eventually agreeing to civilian participation after months of protests in Sudan, they formed the Transitional Sovereignty Council, and assumed the two senior positions. Burhan became chairman and Hemedti became the vice-chairman. The conceit behind the Transitional Agreement was that after two years they would surrender power to a civilian government. Of course, once the two commanders ran out of extensions in October 2021, they dissolved the transitional agreement and dismissed the civilian members of the government.

This created a dynamic in which al-Burhan and Hemedti could no longer govern under the fiction that they were preparing for a civilian transfer of power. Tension between the two commanders had been building for months before the eruption of violence on April 15. The Rapid Support Forces had grown from 7,000 troops in 2014 to perhaps 100,000 largely light infantry troops by 2023. In particular, tensions centered around issues of command and control. Did the RSF report to the SAF? Could they be integrated into one another? Would there be a transition to civilian rule? A final attempt to resolve these issues was launched through the December 2022 Framework Agreement. This agreement broke down after only a few months, allegedly because of a dispute over the timeline to begin integrating the two armed forces. The SAF declared that full integration should be completed in two years, while the RSF suggested ten years.

When violence broke out, it was assumed that despite the RSF initial victories, explained as a result of surprise and full mobilization, that the superior weaponry of the SAF and bandwagoning among both international and domestic actors to the legitimate armed forces of the country would quickly overwhelm the RSF’s tactical advantages. In particular, it was assumed that the SAF’s airpower and heavy artillery would gradually degrade the RSF’s light infantry.

What we will investigate is why most domestic and international actors are ambivalent about choosing between the RSF and SAF. This ambivalence undermines what many analysts initially expected would be an overwhelming SAF advantage.

The Failure of International Bandwagoning

While it would have been reasonable to assume that al-Burhan and the officer corps of the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) would be able to command the diplomatic initiative during the outbreak of the battle for Khartoum, numerous political and diplomatic mistakes undermined their international position. The Sudanese analyst Yaser Zeidan wrote in Foreign Policythat, “the best outcome of the ongoing war would be the Sudanese Armed Forces eliminating the RSF to prevent a second Somali scenario–where militants have long vied with the state for control.”

The assumption was that the international community would see the conflict in Sudan as a battle between an unlawful militia and the state, not as a battle between two generals. Yet, while some members of the Sudanese diaspora promoted this framing in the international media, others like the Sudanese analyst Kholood Khair was quoted in the New York Times describing the conflict as the result of the fact that, “the generals faced no accountability.” Khair reminded the world that, “the abductions, disappearances, sham trials, unlawful detentions–the international community turned a blind eye to all of that for the sake of a political process that has now gone horribly wrong.”

Many of the most influential voices in the Sudanese diaspora did not rally to the defense of the SAF in the Western press. Early in the crisis, the US National Security Council spokesperson John Kirby declared when asked about the 16,000 US citizens trapped in Sudan that, “the safest thing for Americans to do, those who have decided to stay … is to shelter in place and not move around too much the city of Khartoum.” Later in the same interview when asked by George Stephanopoulus if there was anything the US could do to help bring down the tension, Kirby said, “we are working every single day with these two military leaders.” to get them to abide by the ceasefires they have signed. In the process, it is obvious that the United States government was putting Burhan and Hamdan Daglo on an equal or near equal footing. This has been reflected as well by the organization of US-Saudi negotiations in Jeddah.

The SAF have also failed to gather the support of their East African neighbors, repeatedly rejecting Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) mediation. In particular, the SAF has rejected the selection of Kenyan President William Ruto as head of the Quatart Group, tasked with ending Sudan’s three-and-half-month conflict. On July 25, Yasser al-Atta, the assistant commander-in-chief of the Sudanese Armed Forces, angrily announced in a widely circulated video that, “President Ruto should leave East African reserve forces alone, and instead he should come along with the Kenyan army to face us.” Lt. Gen. al-Atta was responding to the July 10 proposal by IGAD, which “further resolves to request the East Africa Standby Force (EASF) summit to convene in order to consider the possible deployment of the EASF for the protection of civilians and guarantee humanitarian access.”

The Rapid Support Forces sent a diplomatic delegation to Addis Ababa for the IGAD headed by Yossif Izzat, while the SAF refused to attend. Yousif Izzat similarly welcomed Egyptian mediation efforts held a few days later on July 13 and attended the Jeddah talks. His strategic victory is to have gotten his delegations recognized on the same level as the SAF. While the SAF has antagonized many of Sudan’s neighbors by attempting to forum shop and demanding their own ability to choose moderators.

The SAF has found itself on the diplomatic back foot as it tries to rally support in East Africa in part because of the memory of the Sudanese Civil War, in which the SAF found itself on the opposite side of the conflict from states like Kenya, Uganda, South Sudan and Ethiopia. From 2020––2022 Sudan and Ethiopia have frequently found themselves in border skirmishesin the Al-Fashaga region. Similarly, Sudanese relations with South Sudan have been complicated by ongoing border disputes in the two areas of South Kordofan and Blue Nile State. These conflicts have complicated the SAF’s ability to attract support from the other Sudanese militias, the largest of which is the Sudanese People’s Liberation Movement–North. The SAF has been able to incorporate leaders like Malik Agar in their campaign against the RSF, but other prominent leaders of SPLM-N such as Abdelaziz Adam Al-Hilu have launched attacks against SAF forces in Blue Nile and South Kordofan sometimes with suspected coordination from the RSF. Many of the other prominent former rebel groups in Sudan have also remained curiously quiet in the present conflict, even the other signatures of the Juba Peace Agreement that was intended to help integrate these movements into the government.

Internationally there is ambivalence because of the SAF’s historic record of human rights abuses—not that the RSF is innocent of similar crimes—and its role as an incubator for Islamists since Omar al-Bashir’s coup d’etat against the democratically elected al-Sadig al-Mahdi in 1989. Currently, both Saudi Arabia and especially the United Arab Emirates (UAE) have mobilized to fight currents of political Islam in the region, and therefore find the SAF’s historic ties to the Sudanese Islamic Movement anathema. Despite this common aim, due to rising tensions between the two Gulf states, Saudi Arabia tends to align with the SAF while the UAE is logistically supporting the RSF. Amjed Farid, former advisor to Prime Minister Abdallah Hamdok, argues that this framing of the conflict as between the Islamists and RSF has been repeated by Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs Mary “Molly” Phee. Given the Islamists’ dismal human rights record, and failed international diplomacy, framing the war as a conflict between the RSF and Islamists, rather than a rebel security force and the state military, leads to the ambivalence we currently observe. Nevertheless, the international framing ignores the fact that many former Islamists are part of the RSF, such as former VP Hassabo Abdelrahman.

The SAF Failure to Consolidate Domestic Support

If Burhan had failed internationally in rallying support for the SAF, why is it that he also failed domestically? Since the inception of the war, there has been a complete absence of numerous government forces such as the police force with the exception of the Central Reserve Force unit—which have not been involved in any fighting. Meanwhile, the popular resistance committees, which have organized so much of Sudan’s social life since the overthrow of Bashir’s regime in 2019 as well as continuous protests against both the SAF and RSF, have also refused to take sides in the conflict.

A common view among Sudanese activists is that “The only solution we can accept now is the two generals stop the fighting and hand over power to a civilian government. The only solution we see for Sudan is the only demand we have been trying to achieve through a revolution since 2018 – a full civilian rule.” While many may disagree about how to settle the conflict, the sentiment that this is not a war in which the Sudanese people should take sides remains pervasive. As a result, the RSF succeeded in framing the conflict as the war of the two generals. This framing has hampered the ability of the SAF to use its standing as the legitimate institution of the state in order to gather support over time.

Conclusion

The United States should lean into the ambivalence about the two parties in order to work with Saudi Arabia, UAE, Chad, the African Union, and IGAD to create a negotiated settlement, where the leadership of both armed parties surrender power in exchange for immunity. This is not to say that both belligerents are on equal footing, but to demonstrate that a decisive victory for either party risks destroying the very fabric of the nation, continuing the cycle of bloodshed which Sudan has experienced. If either side monopolizes violence, they will seek vengeance on communities that they deem disloyal. This is why it is vital for Sudanese civilians, including politicians, businessmen, youth and traditional leaders, to come together to set the stage for a foundational period, during which a new social compact can be established. During this period it will be incumbent for the Sudanese armed forces, paramilitary forces, and rebel movements to be reorganized under civilian control.