The Central African Republic faces many challenges in adopting digital financial solutions, but it can learn from other post-conflict countries and improve its approach.

SUMMARY

Access to internet connectivity is very low in the Central African Republic and access to stable electricity is just as bad. Yet, the country is pursuing digitalization as a solution to the lack of financial services in its post-conflict environment. Endeavors like using Bitcoin and Sango Coin—both of which heavily depend on internet connectivity—as legal tender, coupled with low cybersecurity awareness raises questions about the viability of such digital solutions. How the government promotes security as part of its digital transformation of financial services will be very important to the future of the country’s citizens.

This paper reviews cybersecurity governance challenges that arise as a result of adopting digital financial solutions and how the Central African Republic plans to mitigate them. It then compares the country’s approach to how other post-conflict countries such as Afghanistan, Liberia, and Somalia have addressed these challenges when adopting a digital finance strategy. Based on lessons learnt from these other post-conflict countries, the paper makes recommendations that might help improve the Central African Republic’s approach.

INTRODUCTION

There is no standard definition of digital finance, but there is a consensus that it enables the delivery of financial services such as payments, savings, and credit facilities through the use of digital tools and infrastructure without the need to visit a bank branch or financial service provider.1 Recent scholarship has found that in the right environment digital finance can help improve financial inclusion.2 This use of information and communications technology infrastructure to deliver financial services is particularly important in countries where civil infrastructure like roads is lacking and distances to banks are long.

According to the United Nations, the goal of digital financial services is to include people without bank accounts—especially those in developing countries—in the financial system.3 Some of the reasons people in developing countries do not own bank accounts include the long distances to banks, the high cost of maintaining bank accounts, the lack of documentation required to open accounts, and the lack of trust in banks.4 Cameroon, which neighbors the Central African Republic, is the larger and more stable economy in the sub-region. In Cameroon, the top three reasons for people to be unbanked are that they have no money to save (39 percent), no regular income (32 percent), or no job (24 percent).5 In the Central African Republic, in addition to these reasons, the problem was exacerbated by the violent domestic conflict between 2013 and 2015. According to the government, the conflict destroyed the economy as instability and insecurity hurt investment and the private sector.6 While the post-conflict recovery is offering people opportunities to earn income again, the human displacement due to the conflict7—including from neighborhoods of the capital, Bangui—placed people even farther away from the few financial institutions that survived. Moreover, the absence of the state in many parts of the country outside Bangui means that many people might not have the requisite documentation to open a bank account.8

President Faustin-Archange Touadéra has claimed the government is actively engaged in finding solutions to the financial inclusion challenges the country faces.9 The government is now paying civil servants’ salaries using mobile money services in a project called Patapaye. It is adopting Bitcoin and cryptocurrencies as legal tender,10 and it is even engaging in the tokenization of natural resources including extracted minerals and land.11 Tokenization of assets involves the digital representation of physical assets on the blockchain or distributed ledger. In short, the government has approached digital finance as a primary solution to its challenges.

As the level of access to computers in the Central African Republic is at 0.96 percent of the population and internet penetration at 8 percent (compared to 13.81 percent and 29 percent respectively in Cameroon),12 one cannot help but question the viability of a digital solution. Such low access to digital life also leaves most people and institutions unaware of cybersecurity risks and of what they need to do to protect themselves.13 Therefore, how the country undertakes securing the digital financial system is key for the success and sustainability of its agenda for the digital transformation of financial services.

This paper reviews cybersecurity governance challenges that arise as a result of adopting digital financial solutions and how the Central African Republic is mitigating them. It sets out the state of play of digital finance in the Central African Republic, including who the players are, the challenges faced in effectively securing digital finance in the country, and ongoing efforts to solve some of these. This is followed by a comparative analysis of the approach being used by the Central African Republic to solve these challenges and those used by other post-conflict countries when adopting a digital finance strategy. Finally, it makes some recommendations as to areas that require immediate action to bring about security of the budding digital finance industry in the country.

DIGITAL FINANCE STATE OF PLAY

The Central African Republic is a member of the Economic and Monetary Community of Central Africa (CEMAC), whose objectives include economic and monetary integration. To achieve its goals, the CEMAC created seven organs to manage various aspects of the monetary and economic zone.14 These include the Conference of Heads of State, the Council of Ministers, the Ministerial Committee, the CEMAC Commission, the Bank of Central African States (BEAC), the Development Bank of Central African States, and the Banking Commission of Central Africa (COBAC).

The BEAC is charged with organizing the monetary system, banking, financial, and exchange rate regime of all member states, while the COBAC monitors, regulates, and controls the performance of banking activities. Until 2018, CEMAC regulations authorized only banks and microfinance institutions to issue electronic money. A regulation on payment services that allows other institutions like telecommunications companies and fintech firms to issue electronic money was adopted on December 21, 2018.15

The civil conflict in the Central African Republic between 2012 and 2015 led to a complete collapse of its economy and public services, with many banks and microfinance institutions closing their operations. With no access to financial services and no road infrastructure, it became a challenge for civil servants to receive their salaries. In 2019, the new government partnered with Orange to pay civil servants’ salaries through mobile payments and digital services.16 Orange still had to partner with Ecobank to deliver the program in line with its Africa Strategy,17 which was based on CEMAC’s pre-2018 electronic money regulation that hindered the ability of non-banks or microfinance institutions to issue electronic money directly.

Touadéra’s remarks in 2022 about impenetrable bureaucracies in the traditional financial system not offering countries such as the Central African Republic the possibility to be competitive suggested that his vision for the country does not fully align with the positions of the regional regulator.18 The president also noted the benefits of virtual transactions, such as speed of execution and lower cost, and the need for innovative solutions to finance critical economic sectors. The Central African Republic’s high external debt makes it even more difficult for the country to access traditional forms of financing.19

A strong desire to address the challenges resulting from the conflict appears to drive the government’s approach toward financial inclusion and digitalization by adopting the cryptocurrency Bitcoin as legal tender, making the Central African Republic the second country to do so after El Salvador. Going further, the National Assembly supported by the president’s office seeks to develop a national crypto token called Sango Coin,20 built on the Bitcoin network.

Sango Coin, which is part of the broader Sango project (see next section), is different from tokens such as Bitcoin and Ethereum in that it is a layer 2 blockchain built on top of a layer 1 blockchain (Bitcoin) with the intention to extend the layer 1 protocol by offering smart contracts and providing decentralized finance services. Layer 1 blockchains, on the other hand, are base layer blockchains (also known as “mainnet”). Because of its ability to provide decentralized finance services, Sango Coin offers the Central African Republic a way to completely digitize its financial services and to make it accessible to people with little or no access to Bangui, where the majority of banks are based. It also offers a way to tokenize the country’s abundant natural resources and to raise badly needed funds for infrastructure and development projects.

Apart from the government, there are a few private sector players offering digital financial services in the Central African Republic, which are examined below.

DIGITAL FINANCE PLAYERS

Only a few digital finance players operate in the country, with most focusing on offering digital marketplaces and e-commerce services and platforms.

Nabeoko

Nabeoko is an online mall that connects small producers and micro-, small-, and medium-sized enterprises to online consumers locally and internationally.21 In the words of WinstantPay, the company behind it, Nabeoko’s market strategy is financial inclusion for small- and medium-sized enterprises.22 This is a strategy chosen in recognition that agriculture remains the main source of economic activity for the country and that non-tradable goods and services dominate the urban economy.

Marché Banguissois

Marché Banguissois is a start-up aiming to bring together economic operators from all sectors in the domestic market and to connect them to international markets.23 With a vision to “establish itself as a leader in the field of the digitalization of goods and services,” Marché Banguissois provides e-commerce and digitalization of goods and services to the country’s people. As with other fintech startups in the Central African Republic, the sociopolitical crisis and frustration at the delay to progress in the country drove the establishment of the firm.

KETE Cash

KETE Cash is a decentralized payment platform aiming to meet the growing needs of local financial transactions.24 The platform, which was founded by Mamadou Moustapha Ly who also oversaw the development of the Sango Coin, is used primarily for money transfers, payment of bills, and payment of scholarships and salaries. KETE Cash seeks to fill the financial services gap left by the destruction of bank branches during the war. However, a search on the internet returns very little about the platform, with only a Facebook page found. A Google search did not return any website nor was one included on the Facebook page. Nevertheless, blogs suggest KETE Cash is a key player in financial inclusion in the country, competing with Western Union in Bangui.25

Harvey & Co

Harvey & Co is another fintech start-up that is apparently developing a transport fare settlement platform and electronic wallet.26 Like most of the fintech startups in the country, it has no online presence. It is only mentioned online on the website of the Central African Republic Technology Entrepreneurship Accelerator, a project of the Center for Assurance Research and Engineering, which carries out research on cybersecurity and is housed in George Mason University’s Volgenau School of Engineering in the United States.

This is telling of the general state of play of digital finance in the Central African Republic. It appears that the low internet penetration in the country reduces the necessity of start-up firms having an online presence, despite their main service offerings being of a digital nature.

Patapaye Initiative

Patapaye is a public-private partnership between the government and Orange.27 It aims to address issues related to the payment of salaries to civil servants after the war destroyed or caused bank branches to close, as well as issues related to the absence of road networks connecting people to Bangui. The initiative enables civil servants to receive their salaries over the mobile telephone network direct to their phone wallets without an internet connection. Despite the initiative’s potential for improving financial inclusion, challenges such as high transaction fees, insufficiently informed users, and complex identity checks have limited its success thus far. Figure 1 shows the registration process for Patapaye.

The initiative is also meant to address corruption and fraud, but there is no information available to judge to what extent this objective has been pursued.

The Sango Project

The Sango project is a cryptocurrency and digitalization initiative of the government.28 As part of the initiative, the government has made Bitcoin legal tender in the country. It has also developed a national cryptocurrency called Sango Coin and a digital monetary system based on the Bitcoin blockchain.

While the Sango project aims to eliminate the need for any physical administrative interaction with the government, another primary goal is to tokenize the country’s natural resources, apparently to ease access to investors, democratize investments, and encourage fractional investment. The project’s “genesis paper” lists gold, uranium, iron, limestone, diamonds, lithium, and graphite among the natural resources that will be tokenized.

The Sango project also aims to offer a crypto-wallet. This would be a user-friendly multi-platform application compatible with point-of-sale systems for businesses to accept crypto-payments and integrated automatic accounting system for enhanced collection of value-added taxes. It would also offer digital identity and ownership solutions, using biometrics and custom non-fungible tokens to enable locals and foreigners to manage land purchases and ownership as well as to obtain e-residency and citizenship by investment.

The Sango project promises to modernize and uplift the economy, increase the general population’s access to finance and infrastructure, and address financial exclusion. Touadéra has argued that a digital monetary system and crypto-wallets make traveling to bank branches unnecessary. However, the project faces challenges. The principal one is the Constitutional Court having declared the sale of citizenship, the creation and sale of e-residence, and the sale of land and natural resources as unconstitutional in August 2022.29 Touadéra promised to “take all appropriate measures to avoid potential violations of the Constitution raised by the Court,”30 but it is yet to be seen how he intends to do so.

Another challenge the Sango project has encountered is the demand by the BEAC governor that the Central African Republic consider annulling its Bitcoin law, citing violations of policies and agreements of the Central African Monetary Union such as competition with the Central African franc used by all six countries in the CEMAC and the unilateral establishment of a new currency beyond the control of the BEAC.31 However, the BEAC later agreed to oversee the project and help develop a normative framework governing crypto assets in the CEMAC, including promising to pursue actions in favor of financial inclusion in the region. This allowed the Central African Republic government to proceed with the Sango project without a conflict with the regional regulator.32 States, central banks, and regional banks like the BEAC usually issue central bank digital currency as a digital form of their physical money or fiat currency. The Sango Coin is different from these however, as it is backed by Bitcoin, another cryptocurrency, rather than fiat currency. It remains to be seen how the BEAC intends to reconcile these two separate concepts from a policy and regulatory perspective.

Mobile Money

The Central African Republic has three mobile telephony operators—Mouv, Telecel, and Orange—each of which offers a mobile money service to its customers. Telecel and Mouv offer traditional money transfer, deposit, withdrawal, and payment services, while Orange offers the ability to transfer money to any of the six CEMAC countries in addition to these traditional services.

Unlike the banking sector, which is regulated at the regional level, telecommunications services are regulated by a national authority called the Autorité de Régulation des Communications Electroniques et de la Poste de la République Centrafricaine. However, mobile money and electronic payment services are regulated by the regional regulator COBAC, leaving the mobile telephone operators under COBAC’s supervision and regulation in this regard.

Banks

Four banks33—Ecobank, Banque Populaire Maroco-Centrafricaine (BPMC), Commercial Bank Centrafrique, and Banque Sahélo-Saharienne pour l’Investissement et le Commerce—resumed operations after the conflict. Based on the products and services listed on the four banks’ websites, only Ecobank appears to have innovative services that truly leverage the combined benefits of digital and mobile technology. Ecobank’s mobile banking application offers the bank’s clients and others a platform to access financial services. It offers money transfers and bill and utility payments to every app user, while in-store payments and mobile banking services are available only to the bank’s customers.

CHALLENGES IN SECURING DIGITAL FINANCE

CYBERSECURITY POLICY

The Central African Republic does not have a national or sector-specific cybersecurity strategy, nor a national governance roadmap for cybersecurity. In the 2020 Global Cybersecurity Index, the country ranked 176th, only ahead of Maldives, Honduras, Djibouti, Burundi, Eritrea, Equatorial Guinea, North Korea, and Yemen.34 A CEMAC directive requires member states to develop cybersecurity and cyber crime policies, including measures and laws aimed at protecting electronic communications.35 Despite this directive, the country has no national regulation or law on cybersecurity or cyber crime. The Ministry of Posts and New Technologies is responsible for cybersecurity,36 but there is no specific law enforcement division to investigate cyber crimes.

While cybersecurity policy is set at the national level, it would benefit from the influence of a regional authority. For example, the banking regulator COBAC could set minimum cybersecurity requirements for financial service providers operating in the CEMAC countries. Within the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), which has a binding directive to this effect, almost all member states have cyber crime legislation in place.37 Such a requirement might also prompt the national cybersecurity regulator to develop a wider cybersecurity policy and enforcement.

COMPUTER INCIDENT RESPONSE TEAM

The Central African Republic does not have a national Computer Incident Response Team (CIRT). There is also no record of it having any sector-specific CIRT. Local academics have called on the government and private sector to establish one as part of a broader national cybersecurity policy.38 They have also suggested that individual companies put in place security operations centers in order to effectively manage incidents.

AWARENESS AND SKILLS

The majority of those starting businesses in the Central African Republic are inexperienced and from the informal sector.39 They not only lack knowledge and understanding of the complex relationship between digital services and cybersecurity, they are also not supervised and regulated.

The country faces serious challenges and limitations in the use of information and communications technology (ICT). Cybersecurity skills are not taught at school. Even if they were, only a very small minority of the population would be aware of or have the skills to protect ICT infrastructure and services given the very low literacy rate.40

Despite the very low cyber literacy in the country, the genesis paper of the flagship Sango project does not mention how skills required by consumers to use cryptocurrencies will be developed.41 Neither does it say if or how operational and delivery-side skills of the project, including critical cybersecurity skills, will be developed.

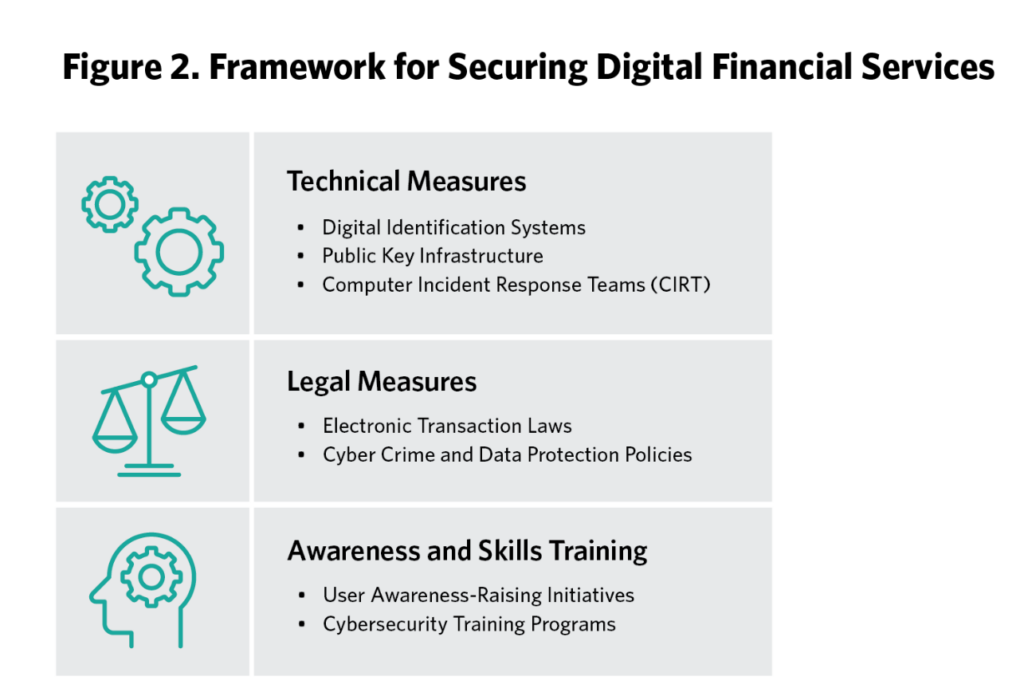

FRAMEWORK FOR SECURING DIGITAL FINANCIAL SERVICES

Securing digital financial services requires states to adopt best practices, policies, and regulatory initiatives that advance infrastructure security and resilience. This section outlines the framework that is used here to compare the Central African Republic’s approach to securing digital finance with the approaches of three other post-conflict countries.

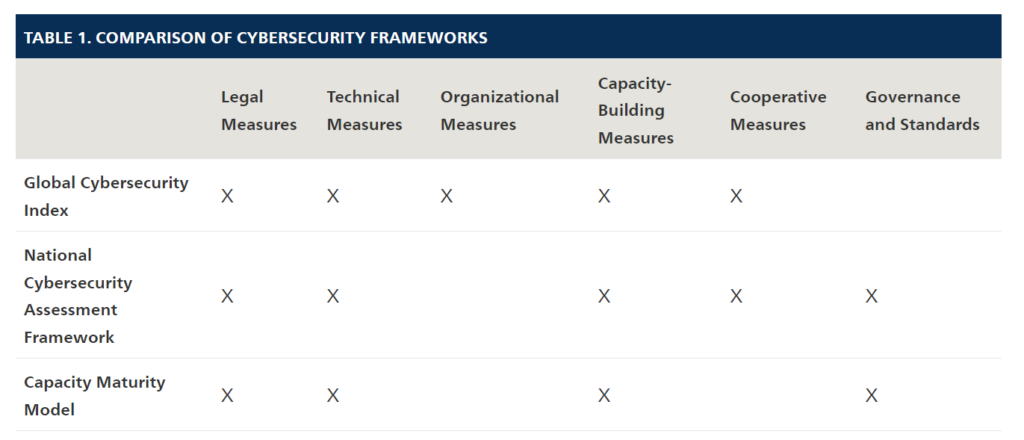

To identify measures that advance the security and resilience of digital financial services, an in-depth review was performed of the International Telecommunication Union’s Global Cybersecurity Index pillars,42 the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity’s National Cybersecurity Assessment Framework clusters,43 and the Global Cyber Security Capacity Centre’s Cybersecurity Capacity Maturity Model for Nations.44 All three frameworks have the common objective of measuring and assessing the maturity of countries’ cybersecurity capabilities, and they group best practices into broad categories.

Based on an evaluation of these best-practice categories, three are identified as critical to securing digital finance: awareness and skills training, technical measures, and e-commerce legal measures. These three categories were present in all three frameworks, while categories such as organizational, cooperative, and governance and standards measures were not present in all frameworks (see table 1).

The categories are further broken down into specific aspects that play significant roles in securing digital financial services. Technical measures include digital identification systems, national public key infrastructure, and CIRTs; legal measures include electronic transaction laws and cyber crime and data protection policies; and awareness and skills training include initiatives to raise user awareness and cybersecurity training programs.

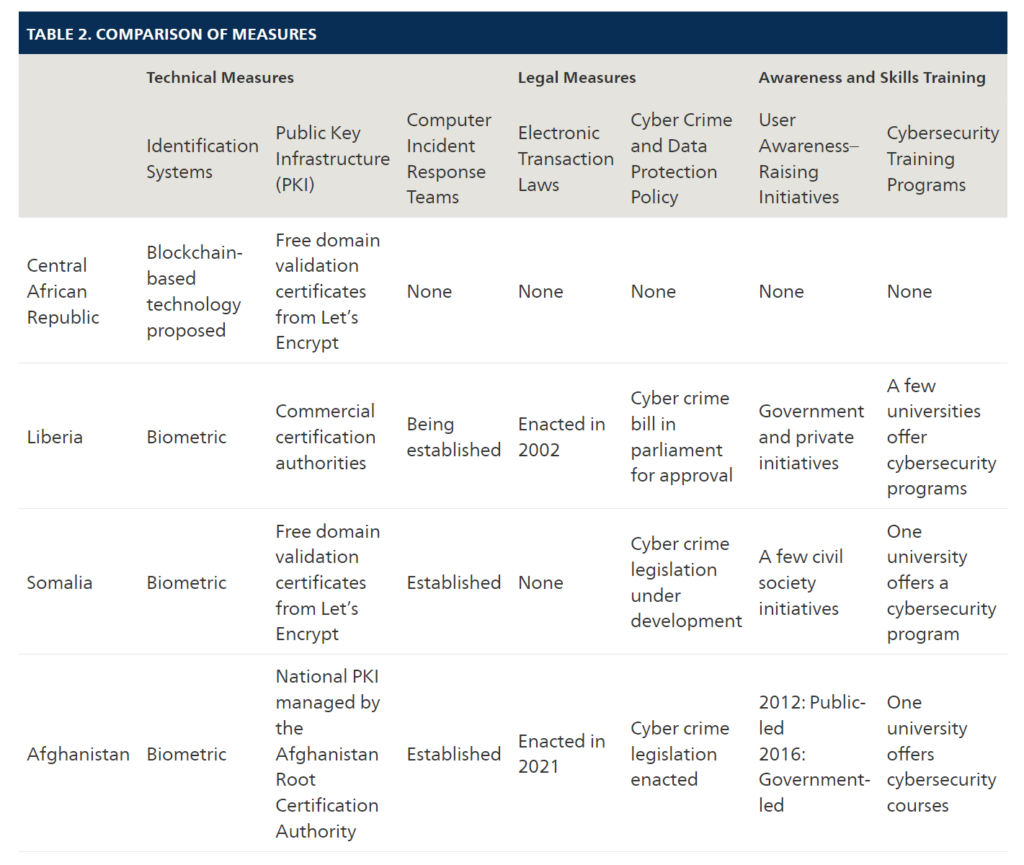

COMPARING THE CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC TO OTHER POST-CONFLICT COUNTRIES

To compare the measures the Central African Republic has taken or plans to take to secure digital finance with those in similar post-conflict countries, the paper looks at how Afghanistan, Liberia, and Somalia address digital financial security, using the framework set out above. These three other countries have, in the recent past, gone through a post-conflict phase similar to the one in which the Central African Republic is now: Liberia after the second civil war of 1999–2003, Somalia after its federal government was established in 2012, and Afghanistan after the first post-Taliban government was elected in 2001. Table 1 summarizes how the Central African Republic compares to the three countries in each of the areas identified by the framework.

TECHNICAL MEASURES

Digital Identification Systems

For security reasons, including fulfilling anti–money laundering requirements and meeting international standards, there is a need to identify owners of financial accounts. A wide range of studies show that identification systems are central to financial inclusion and, in particular, that digital identification systems are critical for the success of digital financial services.45 According to the World Bank, up to 1 billion people worldwide are without an official proof of identity and up to half of them reside in sub-Saharan Africa (see figure 3).

It can seem odd that efforts to improve financial inclusion in Africa follow a digital financial services approach, given that the majority of the unbanked population lives in rural areas and is less educated and that lack of identification is likely to be cited by less educated or rural residents as a reason for not owning a bank account.46 However, other studies find that digital identification can be an effective solution to the problem of identification.47 The World Bank defines digital identification systems as “those that use digital technology throughout the identity lifecycle.”48

The Central African Republic has stated its intention to use blockchain technology to provide digital identity services to its citizens as part of the Sango project.49 Afghanistan, Liberia, and Somalia have taken a different approach in implementing a digital identification system, using a traditional biometric one.50 Physical identification cards are issued to each citizen based on biometric information collected and a unique social security number.

Public Key Infrastructure

Public key infrastructure (PKI) is a system of policies, procedures, software, and institutions that manages the authentication, distribution, and revocation of digital certificates. The digital certificates are usually signed by a certification authority, while registration and processing of user requests can be delegated to a registration authority (see figure 4).

Despite the possibility that quantum computing might pose challenges to it, there is a consensus that PKI is required for electronic authentication, commerce, and integrity on the World Wide Web.51 Digital identification also often requires PKI to function as it makes use of digital certificates and signatures issued to citizens.

According to one study, online vendors are happy to take orders from buyers, whether they have a PKI certificate or not, and therefore PKI does not secure electronic commerce as claimed.52 While this is correct in the respect of the necessity of client-side certificates in electronic transactions—since other authentication mechanisms, such as password-based authentication, are available and could be used—it is nevertheless critical on the internet today that vendors are verified by their clients’ browsers to validate that they are indeed who they claim to be to prevent financial fraud online. Also critical is the need for e-commerce vendors to provide an encrypted channel for their customers to enter their payment details privately and safe from the prying eyes of cybercriminals.

Governments in developing countries believe correctly that a secure cyberspace is key to economic development and that secure online transactions—including e-government, e-commerce, e-finance, and e-learning—depend on an efficient and effective PKI.53 They are therefore deploying national PKIs to safeguard their cyberspace and improve trust in electronic transactions and services.

The Central African Republic has not yet defined a PKI policy, nor has it indicated publicly its intention to deploy one for e-commerce purposes. The government does not have any e-government services, but it has a web presence with various government websites that are secured using free PKI domain validation certificates from the nonprofit organization Let’s Encrypt.

Liberia chose to use commercial providers rather than deploy a government-run national PKI, essentially adding another authority to the PKI structure. In this model, a recognition authority—the deputy registrar appointed by the minister of foreign affairs, as set out in the Electronic Transaction and Electronic Signature law54—is responsible for recognizing application certificate authorities authorized to issue PKI certificates in the country.

Afghanistan established a national PKI infrastructure called the Afghanistan Root Certification Authority under the Ministry of Communications and Information Technology.55 Its tasks include promoting confidence in the integrity and reliability of data messages and electronic commerce, as well as promoting egovernment services and transactions with public and private bodies, institutions, and citizens.

Like the Central African Republic, Somalia does not have any PKI policy and uses the free domain validation certificates from the Let’s Encrypt service to protect its web services.

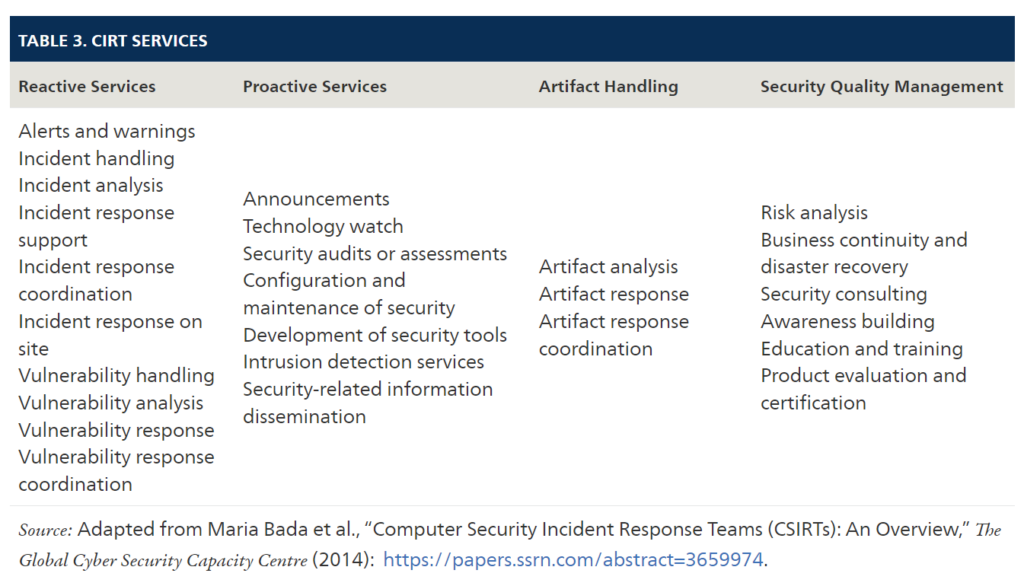

Computer Incident Response Teams

At a minimum, CIRTs—whether national or not—provide incident handling services and play an educational role with regard to cybersecurity. Table 3 shows a complete list of services provided by CIRTs.

The International Telecommunications Union is of the view that to reliably address and respond to cyber threats and incidents in a country, effective mechanisms and institutions at the national level are necessary and that a national CIRT is key to that. In this regard, the lack of a CIRT is a critical issue if the Central African Republic’s economy is to be digital-first as the government intends. The government must establish a national CIRT to respond to cyber incidents adequately and effectively.

In Liberia, a national CIRT has not yet been established, but an assessment of the readiness to implement one was successfully completed.56 In 2019, the minister of posts and telecommunications disclosed that the government was working on establishing a national CIRT as a central part of Liberia’s cybersecurity architecture and as the focal point for cybersecurity incidents and cyber crime.57

Afghanistan has established a national CIRT, called AFCERT, to operate as the first responder to cyber and computer incidents in the country.58 Similarly, Somalia has established the Somalia Computer Emergency Response Team/Coordination Center (SomCERT/CC) as a national CIRT.59 Its role is to secure the country’s cyberspace and provide an official point of contact to handle cybersecurity incidents.

Figure 5 shows how long it took each of the three countries from the end of active conflict to when a CIRT was established. It took Somalia seven years to establish one, Afghanistan nine years, and Liberia eleven years just to perform a CIRT assessment. By comparison, it has been eight years since the conflict in the Central African Republic ended.

ADOPTION OF E-COMMERCE LEGISLATION

Electronic Transaction Laws

To promote legal certainty and confidence in electronic transactions, including financial transactions and electronic commerce, governments usually enact laws that recognize the legal equivalence between paper-based and electronic forms of transactions. The admissibility and evidentiary weight of electronic evidence are some of the challenges such laws also seek to address.

Signatures are often required by parties to an agreement to express their intent to be bound by its contents. In electronic commerce, agreements are made without any physical meeting of the parties, and electronic signatures are required to express the intent to be bound by an electronic document. As a result, “electronic signatures must serve the same essential functions that we expect of documents signed by handwritten signatures.”60 Many developing and least developed countries already have electronic transaction laws, which are often the first step toward deploying and using a national PKI.

Afghanistan and Liberia have e-transaction laws,61 while Somalia has yet to pass one. The Central African Republic also does not have any e-transaction laws.

Cyber Crime and Data Protection Policy

Developing countries, especially African ones, are increasingly targets of cyber crime because they are seen as easy targets and low-hanging fruit by cybercriminals.62 This is in part due to the growing use of digital-first solutions and strategies to solve challenges in financial services and other sectors in these countries, which increases the digital presence and dependence of society. In every facet of the economy and community—such as banking and financial services, health, and farming—information and communications technologies are at the center of the solutions being developed.

Another reason for the increasing number of cyberattacks is vulnerable systems and very lax or poorly implemented cybersecurity policies, which are often the result of low or zero budget allocation for cybersecurity and a severe shortage of cybersecurity skills in the workforce.

Lack of public awareness about cybersecurity and safe use of the internet is another significant contributor to such weakness. The average internet user in Africa is often not aware of basic cyber hygiene practices, such as using complex passwords, using different passwords for different accounts, not sharing passwords, using multifactor authentication, ensuring privacy, and keeping apps and software up to date.

Finally, weak legislation and very poor or no law enforcement of cyber crime is another reason for the attacks. Not only do many developing countries lack adequate legal provisions to fight cyber crime, but their law-enforcement officials and judges are also not well trained to enforce cyber crime laws.

Cyber crime policies in developing countries should take into consideration the pervasiveness of digitalization and the current state of cybersecurity in general. They should be effective, innovative, and enforceable. Innovation in regulation will be a determinant of success when it comes to people being financially included in the digital era in a manner that is safe, secure, and trustworthy.

Afghanistan has legislation for cyber crime and plans to build a forensics laboratory to enhance its investigation capacity. In Liberia, a draft cyber crime bill that aligns with the country’s obligation to adapt its criminal laws to the ECOWAS Directive on Cyber Crime is awaiting legislative approval.63 In addition, the nongovernmental Liberia Cyber Crime Prevention and Mitigation Agency has been established and accredited by the Ministry of Justice.64 Its mission is to enhance the ability of public and private institutions to prevent and mitigate cyber crimes. It should do so by providing technical assistance to judicial and law-enforcement entities by developing standards and strategies to combat cyber risks, conducting cyber crime assessments, and providing cyber defensive capabilities to the business community.

In Somalia, an appropriate legal framework for cybersecurity and cyber crime is being developed. A Ministry of Communications and Technology terms-of-reference document for technical advisory services for the Development of a National Cybersecurity Policy, Strategy, Governance, and Institutional Structure as well as Guidelines for the Protection of Critical Information Infrastructure reiterate how such a legal framework is one of the top two national priorities with regard to cybersecurity.

The Central African Republic does not yet have any cyber crime or cybersecurity laws or policies, which are needed for the implementation of the Sango project and digitalization of the financial ecosystem.

AWARENESS AND SKILLS TRAINING

This category covers initiatives or plans by all stakeholders—including government, the private sector, and civil society and academia—to raise the cybersecurity awareness of users. It also includes the availability of educational and professional cybersecurity training programs.

User Awareness-Raising Initiatives

People remain the weakest link in cybersecurity, often as a result of lack of awareness and poor security practices. The lack of awareness is further exacerbated in communities affected by armed conflicts as general education and literacy are usually affected because of displacement and destruction. With literacy levels and the internet penetration rate very low in the Central African Republic, chances are that very few people are aware of the risks associated with the use of digital finance. Users need to be taught basic safe digital practices that will make it difficult for them to fall victim to cyber crime, like not sharing passwords, changing default passwords, using complex passwords, and enabling two-factor authentication. Such user cybersecurity awareness will thus be a critical determinant of success when it comes to the security of digital finance in the country, as in post-conflict ones in general.

In Liberia, acknowledging the importance of cybersecurity user awareness and to address the need for it, the Ministry of Justice has mandated the Liberia Cyber Crime Prevention and Mitigation Agency to provide cybersecurity education for citizens and institutions. In addition to the government efforts, other stakeholders like the West Africa ICT Action Network civil society group have launched initiatives such as cybersecurity workshops for civil society actors and other activities for users as part of Safer Internet Day.65

There is a similar initiative for Safer Internet Day and Encryption Day in Somalia, where the Internet Society chapter runs activities to raise user awareness about cybersecurity. These appear not to be enough, though, as a study shows that 41.7 percent of internet users in the country are self-taught about cybersecurity and 28.6 percent had no idea what cybersecurity is, despite the fact that 52.4 percent of internet users use the technology primarily to access online banking and money-transfer services.66 The Cybersecurity Department in the National Communications Authority has a mandate to raise public awareness of cybersecurity.

It was reported in 2016 that the government of Afghanistan was active in raising awareness about cybersecurity, in line with its National Cyber Security Strategy published in 2014.67 The social enterprise TechNation runs a program called “Safetya” aimed at creating mass awareness of how people can be safe online.68 The program has been marking Safer Internet Day since 2012.

There does not appear to be any such initiatives or programs initiated by any stakeholder in the Central African Republic. Neither government, nor the private sector, nor civil society is raising public awareness of cybersecurity and cyber crime. The genesis paper for the Sango project does not mention cybersecurity awareness.

Cybersecurity Training Programs

Technology is transforming the global economy and the skills required to run businesses, deliver services, and even govern. Sectors of the economy that become digitalized demand digital skills, such as data analytics, systems engineering, software development, and cybersecurity. These skills are in short supply in developing countries,69 and cybersecurity skills even more so.

Cybersecurity skills shortages are more pronounced in Africa than in any other region. For example, INTERPOL reports that 90 percent of African businesses operate without necessary cybersecurity measures in place.70 Most cyberattacks in the region are not detected by African institutions but rather by foreign threat hunters and researchers.71 And, while many African countries use a lot of foreign expertise and consultants, the INTERPOL report advises against this as overreliance on external actors introduces vulnerabilities and threats to critical infrastructure. Moreover, lack of local skills will cause African economies to stall, as it is expected that even the informal sector, which comprises the majority of Africa’s companies, will be transformed by technology.

Cybersecurity training and course offerings are not common in the four post-conflict countries studied here. In Liberia, the University of Liberia opened a computer and information science program in 2022. It hopes to offer degrees that prepare students in the areas of software engineering, cybersecurity, data science, and networking technology. BlueCrest University College also offers diploma and certificate courses in information security. In Somalia, only Nile University of Science and Technology appears to be offering a cybersecurity course. In Afghanistan, despite the drafting of an IT security training curriculum being one of the goals in the country’s 2014 National Cyber Security Strategy, very few institutions of higher learning offer cybersecurity studies and training.

As mentioned in the previous section, the Central African Republic has no government policy or strategy on cybersecurity training, and it did not consider cybersecurity important enough to be included as a pillar in the Sango project.

Low or absent cybersecurity awareness and skills programs is consistent across all three post-conflict countries compared with the Central African Republic. This might point to the fact that their governments and private sectors pay the least attention to this aspect of digital finance, even though education and awareness are key to the safe and successful digital transformation of financial services and to the stability of the digital economy in general.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

This study shows that digitalization, including of financial services, is the direction post-conflict states trying to transition to stable governance and economies are taking. It also shows that a digitalization strategy that is secure by design is critical for achieving stability. Such a strategy must include all five aspects that make up the framework used to review the four post-conflict countries in the study: identification systems, public key infrastructure, computer incident response teams, electronic transaction laws, and cyber crime and data protection laws.

There appears to be commonality in how the states studied implement some measures, such as CIRTs, electronic transaction laws, and cyber crime and data protection policies. The government generally leads the efforts. However, some countries, such as Liberia, take a hybrid approach to cyber crime policy, combining governmental and nongovernmental dimensions. The government did this by accrediting the nongovernmental Liberia Cyber Crime Prevention and Mitigation Agency to implement the mandate of the Ministry of Justice in the areas of supporting government and private entities initiatives and digital forensics. There is divergence in PKI implementation too, with Liberia taking a private-sector-led certificate authority approach rather than the government running a national PKI.

Comparing the Central African Republic’s measures to secure digital finance to those of the other post-conflict countries highlights the fact that it is still in the very early stages of the process. With its digitalization strategy still in development, it is important that the right security policies and considerations are taken to support and protect the country’s cyberspace and digital economy.

The Central Africa Fibre-Optic Backbone Project, which is currently in development, is expected to significantly remedy the low level state of internet access in the country. Coupled with the Sango project and other digitalization projects, this will see cyber threat levels rise, making it important for cybersecurity to be put at the center of the country’s digitalization strategy and policy. At the time of writing, however, only a digital identification aspiration had been made public by the government. To address the rise in threats and cyber crime expected from the sort of digitalization proposed by the government, proactive measures will be required. This paper recommends the following:

As the Central African Republic progresses with the development of its digitalization strategy, it should prioritize at a minimum a CIRT as well as electronic transaction and cyber crime legislation.

Considering how critical cybersecurity is for a digital-first strategy, the Sango project’s genesis paper should be updated to include cybersecurity policy and regulation as pillars for implementing the project and for digitalizing the financial ecosystem.

Understanding that funding for various initiatives could potentially be a challenge in the early stages, there might be benefit in using Liberia’s PKI model of having a recognition authority authorize commercial certification authorities to issue PKI certificates.

Another challenge the Central African Republic faces is judicial capacity in cybersecurity. In this regard, it could consider Liberia’s model of cyber crime policy, in which the state uses a nongovernmental organization to support the ability of the government and the private sector to perform digital forensics, provide technical assistance to judicial and law-enforcement entities, help develop standards and strategies to combat cyber risks, conduct cyber crime assessments, and provide cyber defensive capabilities to the general business communities.

Cyber awareness and digital finance literacy should be prioritized. For a country with a very low level of literacy, this is even more crucial. The government could work with private-sector players, such as banks, telecommunications companies, and start-ups as well as trusted information intermediaries in communities to elevate end users’ cyber resilience. Enabling and encouraging institutions to provide formal cybersecurity educational programs and professional courses is necessary. The government of the the Central African Republic should make this a pillar in all digitalization policy documents, including the Sango project’s genesis paper and the national cybersecurity strategy. It should then follow up to ensure that the policies and actions from the strategy are implemented.

NOTES

1 Peterson K. Ozili, “Impact of Digital Finance on Financial Inclusion and Stability,” Borsa Istanbul Review 18, no. 4 (December 2018): 329–340, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bir.2017.12.003.

2 Purva Khera et al., “Measuring Digital Financial Inclusion in Emerging Market and Developing Economies: A New Index,” Asian Economic Policy Review 17, no. 2 (2022): 213–230, https://doi.org/10.1111/aepr.12377; “Financial Inclusion in Cameroon,” International Monetary Fund, August 2018, https://commitmentoequity.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/cr18256.pdf; and Ratna Sahay et al., “The Promise of Fintech: Financial Inclusion in the Post COVID-19 Era,” International Monetary Fund, July 1, 2020, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Departmental-Papers-Policy-Papers/Issues/2020/06/29/The-Promise-of-Fintech-Financial-Inclusion-in-the-Post-COVID-19-Era-48623.

3 International Telecommunication Union, “Digital Financial Inclusion,” (United Nations, July 2016), https://www.un.org/esa/ffd/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Digital-Financial-Inclusion_ITU_IATF-Issue-Brief.pdf.

4 Franklin Allen et al., “The Foundations of Financial Inclusion: Understanding Ownership and Use of Formal Accounts,” Journal of Financial Intermediation 27 (2016): 1–30, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfi.2015.12.003;

Jeanne M. Hogarth, Chris E. Anguelov, and Jinkook Lee, “Why Households Don’t Have Checking Accounts,” Economic Development Quarterly 17, no. 1 (2003): 75–94, https://doi.org/10.1177/0891242402239199; and

World Bank, “‘The Global Findex Database 2021,” World Bank, accessed October 28, 2022, https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/globalfindex.

5 FinMark Trust, “Finscope Consumer Survey Cameroon Pocket Guide 2017,” June 30, 2018, https://www.mfw4a.org/publication/finscope-consumer-survey-cameroon-pocket-guide-2017.

6 “Central African Republic: National Recovery and Peacebuilding Plan 2017–21,” Central African Republic, 2016, https://fpi.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2021-05/car_-_main_report_final_en.pdf.

7 “Central African Republic: National Recovery.”

8 “Central African Republic: National Recovery.”

9 “Sango Coin Genesis Event – Official Launch,” YouTube video, posted by “Sango Project,” July 3, 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MMFCAvv50UU.

10 Ryan Browne, “Central African Republic Becomes Second Country to Adopt Bitcoin as Legal Tender,” CNBC, April 28, 2022, https://www.cnbc.com/2022/04/28/central-african-republic-adopts-bitcoin-as-legal-tender.html.

11 “Sango Homepage,” Sango Project, accessed August 25, 2022, https://sango.org.

12 African Union Commission and OECD, “Digital Transformation for Youth Employment and Agenda 2063 in Central Africa,” Africa’s Development Dynamics 2021: Digital Transformation for Quality Jobs (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2021), https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/component/f2e7ffb6-en.

13 Peterson K. Ozili, “Impact of Digital Finance on Financial Inclusion and Stability,” Borsa Istanbul Review 18, no. 4 (December 2018): 329–340, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bir.2017.12.003.

14 CEMAC, “Institutions et Organes,” accessed October 21, 2022, https://www.cemac.int/Institutions_organes.

15 CEMAC, “Règlement N°04-18-CEMAC UMAC COBAC Relatif Aux Services de Paiement Dans La CEMAC”, December 21, 2018, https://www.beac.int/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/REGLEMENT-N-04-18-CEMAC-UMAC-COBAC-du-21-d%C3%A9cembre-2018.pdf; and Danielle Moukouri Djengue, “A Law for Fintech Companies Within the CEMAC Zone,” LEX Africa, December 3, 2019, https://www.lexafrica.com/2019/12/a-law-for-fintech-companies-within-the-cemac-zone/.

16 La Rédaction, “Central African Republic Lauds Patapaye Project Despite Challenges,” CEMAC Eco Finance, accessed August 1, 2022, https://cemac-eco.finance/central-african-republic-lauds-patapaye-project-despite-challenges/; and WinstantPay, “Nabeoko in the Central African Republic: A Small Fish Surfing the Fintech Wave,”September 28, 2020, https://www.winstantpay.com/blog/car-fintech.

17 WinstantPay, “Nabeoko in the Central African Republic.”

18 “Sango Coin Genesis Event – Official Launch.”.

19 Joe Hall, ‘”Bitcoin, Sango Coin and the Central African Republic,” Cointelegraph, January 8, 2023, https://cointelegraph.com/news/bitcoin-sango-coin-and-the-central-african-republic.

20 “Sango Homepage.”

21 WinstantPay, “Nabeoko in the Central African Republic.”

22 WinstantPay, “Nabeoko in the Central African Republic.”

23 CARE Staff, “Marché Banguissois,” Center for Assurance Research and Engineering, February 5, 2022, https://care.gmu.edu/cartea-marche-banguissois/; and

“Marché Banguissois Homepage,” Marché Banguissois, accessed September 13, 2022, https://www.marchebanguissois.com.

24 “Kete Cash,” Facebook page, accessed 13 September 2022, https://www.facebook.com/ketecash/.

25 Corbeau News, “Centrafique: Recommandations Sur La Promotion Des Services Financiers Digitaux,” Bangui.com, August 20, 2018, http://news.abangui.com/h/64106.html.

26 CARE Staff, “Harvey & Co,” Center for Assurance Research and Engineering,” February 5, 2022, https://care.gmu.edu/cartea-harvey-co/.

27 “PATAPAYE | Ministère Des Finances et Du Budget,” accessed October 23, 2022, https://www.finances.gouv.cf/projet/15/patapaye; and

WinstantPay, “Nabeoko in the Central African Republic.”

28 “Sango Intiative,” Sango, accessed June 5, 2022, https://sango.org/initiative.

29 Jean-François Akandji-Kombe, “Centrafrique, Cryptomonnaie Et Souveraineté: Requête Et Décision De La Dour Counstitutionnelle,” Akandji K., August 31, 2022, https://jfaki.blog/archives/13261; Corbeau News, “Notes Explicatives Relatives A La Décision N008/CC/22 Du 29 Aout 2022 De La Counstitutionnelle,” Corbeau News Centrafrique, August 30, 2022, https://corbeaunews-centrafrique.org/notes-explicatives-relatives-a-la-decision-n008-cc-22-du-29-aout-2022-de-la-cour-constitutionnelle-de-la-republique-centrafricaine/; and Faustin-Archange Touadéra, tweet, August 30, 2022, https://twitter.com/FA_Touadera/status/1564738374694539267.

30 Faustin-Archange Touadéra, tweet.

31 Jeune Afrique, “Bitcoin en Centrafrique : le gouverneur de la BEAC contre-attaque,” JeuneAfrique.com, May 5, 2022, https://www.jeuneafrique.com/1344440/economie/bitcoin-en-centrafrique-le-gouverneur-de-la-beac-contre-attaque/; and

RFI, “L’adoption du bitcoin par la Centrafrique inquiète la BEAC et la Banque mondiale,” RFI, May 7, 2022, https://www.rfi.fr/fr/afrique/20220507-l-adoption-du-bitcoin-par-la-centrafrique-inqui%C3%A8te-la-beac.

32 Banque des Etats de I’Afrique Centrale (BEAC), “Communiqué de presse de la session extraordinaire du Comité Ministériel de l’UMAC du 21 juillet 2022,” Banque des Etats de I’Afrique Centrale, July 20, 2022, https://www.beac.int/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Communiqu%C3%A9-de-Presse-CA-Extra-20-juillet-2022.pdf.

33 Banque des Etats de I’Afrique Centrale, “Liste Des Banques Agrees De La RCA AU, 28 OCTOBRE 2014,” October 28, 2014, https://www.beac.int/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Liste_Banques_-RCA-_28oct14.pdf.

34 International Telecommunication Union, “Global Cybersecurity Index 2020,” 2022, https://www.itu.int/epublications/publication/D-STR-GCI.01-2021-HTM-E.

35 Central African Economic and Monetary Community (CEMAC), “Fixant le Cadre juridique de la protection des droits des utilisateurs de réseaux et de services de communications électroniques au sein de la CEMAC [Legal Framework for the Protection of Users of Electronic Communications Networks and Services within CEMAC],” December 19, 2008, http://www.droit-afrique.com/upload/doc/cemac/CEMAC-Directive-2008-07-droit-des-utilisateurs-de-reseaux.pdf.

36 African Union and Symantec, “Cyber Crime & Cyber Security – Trends in Africa,” November 2016, https://securitydelta.nl/media/com_hsd/report/135/document/Cyber-security-trends-report-Africa-en.pdf.

37 Uchenna Orji, “An Inquiry into the Legal Status of the ECOWAS Cybercrime Directive and the Implications of Its Obligations for Member States,” Computer Law & Security Review 35 (July 2019): 105–330, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clsr.2019.06.001.

38 Serge Adouaka, “E-gov and Cybersecurity Strategy for the CAR Post Conflict Country,” January 2021, https://www.academia.edu/44972787/E_Gov_and_Cybersecurity_Strategy_for_the_CAR_post_conflict_country.

39 Adouaka, “E-gov and Cybersecurity Strategy.”

40 Adouaka, “E-gov and Cybersecurity Strategy.”

41 “Sango Genesis Paper,” Sango, accessed September 28, 2022, https://sango.org/genesis-paper.pdf.

42 International Telecommunication Union, “Global Cybersecurity Index 2020.”

43 ENISA, “National Cybersecurity Assessment Framework (NCAF) Tool,” accessed November 17, 2022, https://www.enisa.europa.eu/topics/national-cyber-security-strategies/national-cyber-security-strategies-guidelines-tools/national-cybersecurity-assessment-framework-ncaf-tool.

44 Global Cyber Security Capacity Centre, “The CMM,” accessed December 7, 2022, https://gcscc.ox.ac.uk/the-cmm.

45 Allen et al., “The Foundations of Financial Inclusion;”

Alliance for Financial Inclusion, “FinTech for Financial Inclusion: A Framework for Digital Financial Transformation,” 2018, https://www.afi-global.org/publications/fintech-for-financial-inclusion-a-framework-for-digital-financial-transformation/;

Nnenna Ifeanyi-Ajufo, “Digital Financial Inclusion and Security: The Regulation of Mobile Money in Ghana,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, September 19, 2022, https://carnegieendowment.org/2022/09/19/digital-financial-inclusion-and-security-regulation-of-mobile-money-in-ghana-pub-87949; Sahay et al., “The Promise of Fintech;” and Hogarth, Anguelov, and Lee, “Why Households Don’t Have Checking Accounts.”

46 Allen et al., “The Foundations of Financial Inclusion.”

47 Alliance for Financial Inclusion, “FinTech for Financial Inclusion;”

World Bank, “Data Visualization | Identification for Development,” accessed October 28, 2022, https://id4d.worldbank.org/global-dataset/visualization.

48 World Bank, “Types of ID Systems | Identification for Development,” accessed October 28, 2022, https://id4d.worldbank.org/guide/types-id-systems.

49 “Sango Genesis Paper,” Sango.

50 World Bank, “Identification for Development: Liberia” (Washington, DC: World Bank, June 2015), https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/26438.

51 Ueli Maurer, “Modelling a Public-Key Infrastructure,” in Computer Security — ESORICS 96, ed. Elisa Bertino et al., “Lecture Notes in Computer Science” (Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, 1996), 325–350, https://doi.org/10.1007/3-540-61770-1_45; Carlisle Adams and Steve Lloyd, Understanding PKI: Concepts, Standards, and Deployment Considerations 2 (USA: Addison-Wesley Longman Publishing Co., Inc., 2002); and Andrew Nash, William Duane, and Celia Joseph, PKI: Implementing and Managing E-Security (USA: McGraw-Hill, Inc., 2001).

52 Carl Ellison and Bruce Schneier, “Ten Risks of PKI: What You’re Not Being Told About Public Key Infrastructure,” Computer Security Journal 16 (December 2000), https://doi.org/10.1201/9780203498156.ch23.

53 National Information Technology Agency, “Communications Ministry Launches System to Protect Ghana’s Cyber Space” accessed November 9, 2022, https://nita.gov.gh/communications-ministry-launches-system-to-protect-ghanas-cyber-space/;

ANTIC, “Word of the Director General,” April 27, 2022, https://web.antic.cm/antic.cm/index.php/en/the-agency/general-mangager-s-word; National Information Technology Development Agency, “The National Public Key Infrastructure (NPKI) – NITDA,” 2021, https://nitda.gov.ng/the-national-public-key-infrastructure-npki/; and

Communications Authority of Kenya, “National Public Key Infrastructure,” accessed November 9, 2022, https://www.ca.go.ke/industry/e-commerce-development/national-public-key-infrastructure/.

54 Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Liberia, “Act Amending the General Business Law, Title 14 of the Liberian Code of Laws Revised, By Adding Thereto Chapter 13 to Facilitate the Use of Electronic Transactions for Commercial and Other Purposes, and to Provide for Matters Arising from and Related to Such Use,” June 19, 2002, https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/acc_e/lbr_e/WTACCLBR15_LEG_18.pdf.

55 Afghanistan Ministry of Communications and Information Technology, “Electronic Transactions and Electronic Signatures Act,” 2021, https://mcit.gov.af/sites/default/files/2018-12/Electronic%20Transactions%20and%20Electronic%20Signatures%20Act%20%28for%20comments-final%29.pdf.

56 International Telecommunication Union, “National CIRT,” accessed December 27, 2022, https://www.itu.int:443/en/ITU-D/Cybersecurity/Pages/national-CIRT.aspx.

57 Kwame, “Gov’t to Set Up Nat’l Computer Emergency Response Team,” Liberia News Agency, April 18, 2019, https://liberianewsagency.com/2019/04/18/govt-to-set-up-natl-computer-emergency-response-team/.

58 Afghanistan Ministry of Communications and Information Technology, “Directorates: | Ministry of Communications & IT,” accessed December 27, 2022, https://mcit.gov.af/index.php/en/node/6938.

59 Federal Government of Somalia, “SOMCERT | Somalia Computer Emergency Response Team (SOMCERT),” accessed December 27, 2022, https://somcert.gov.so/.

60 Yee Fen Lim, “Digital Signature, Certification Authorities and the Law,” Murdoch University Electronic Journal of Law 9, no. 3 (September 2002), http://www5.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/MurUEJL/2002/29.html.

61 United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, “E-transactions Legislation Worldwide,” December 14, 2021, https://unctad.org/page/e-transactions-legislation-worldwide.

62 Nir Kshetri, “Cybercrime and Cybersecurity in Africa”, Journal of Global Information Technology Management 22, no. 2 (April 3, 2019): 77–81, https://doi.org/10.1080/1097198X.2019.1603527.

63 Media Foundation for West Africa, “State of Internet Freedom in Liberia 2021,” 2021, https://www.mfwa.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/State-of-Internet-Freedom-in-Liberia-9_14_21-final-revised.pdf.

64 Global Forum on Cyber Expertise (GFCE), “Liberia Cyber Crime Prevention and Mitigation Agency (LCCPMA),” March 26, 2021, https://cybilportal.org/actors/liberia-liberia-cyber-crime-prevention-and-mitigation-agency-lccpma.

65 Safer Internet Day, “Liberia – Safer Internet Day,” accessed February 5, 2023, https://www.saferinternetday.org/in-your-country/liberia.

66 Abas Osman Nur, “Cybersecurity Awareness in Somalia,” Jamk.fi, April 2021, http://www.theseus.fi/handle/10024/501168.

67 Amin Alemi, “Afghanistan Raises Awareness About Cyber Security,” PressTV, August 4, 2016, https://www.presstv.ir/Detail/2016/08/04/478365/Afghanistan-cyber-security.

68 Safer Internet Day, “Afghanistan – Safer Internet Day,” accessed February 6, 2023, https://www.saferinternetday.org/in-your-country/afghanistan.

69 International Financial Corporation, “Digital Skills in Sub-Saharan Africa: Spotlight on Ghana,” May 2019, https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/ed6362b3-aa34-42ac-ae9f-c739904951b1/Digital+Skills_Final_WEB_5-7-19.pdf?MOD=AJPERES.

70 INTERPOL, “African Cyberthreat Assessment Report,” October 2021, https://www.interpol.int/en/content/download/16759/file/AfricanCyberthreatAssessment_ENGLISH.pdf.

71 Nate Allen, Matthew La Lime, and Tomslin Samme-Nlar, “The Downsides of Digital Revolution: Confronting Africa’s Evolving Cyber Threats,” Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, December 2, 2022, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/digital-revolution-africa-cyber-threats/.