Rising vigilantism in Nigeria reflects public cynicism about law enforcement and the judicial system.

Last month, some students of Obafemi Awolowo Hall, a student residential hall at the Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, set upon one Okoli Ahinze, a final year student of the university’s Department of Civil Engineering, and beat him to death. Mr. Ahinze’s assailants had unilaterally accused, tried, and found him guilty of stealing a mobile telephone belonging to another student. Reports of the incident were received by the university community and the general public with a mix of anger and horror. The university authorities ordered an immediate investigation into the circumstances leading to Mr. Ahinze’s killing at the hand of his fellow students, while the police have since arrested at least fifteen students believed to have been linked to the incident.

According to media reports, students at the hall of residence where Mr. Ahinze met his untimely death apparently have their own independent “court system” which regularly metes out punishments to those found guilty of infringing campus law. It is not impossible that Mr. Ahinze’s assailants set upon him after their kangaroo court had imposed the usual sentence of Systematic Maximum Shishi (SMS), a euphemism for unbridled physical violence.

The campus incident encapsulates ongoing concerns about the breakdown of law and order and subsequently a spike in incidents of vigilante justice in Nigeria. Between 2019 and 2022, at least 391 people were reported killed in 279 separate incidents of mob justice across the country. While the majority of these incidents (223) were recorded across the southern region, the range of issues that ostensibly provoked these deadly encounters speaks to a society that is fundamentally ill at ease and impatient with the rule of law. In various parts of the country, irate mobs have descended upon those accused of witchcraft, alleged thieves (of mobile phones), suspected ritualists and alleged internet scammers, individuals accused of destroying campaign posters of political opponents, firefighters who apparently arrived late to the scene of a fire, and police stations where officers on duty refused to release suspects arrested in connection with a particular crime. In one of the more bizarre cases, in March last year, the Anambra State Police Command rescued a woman from a mob in the town of Aguleri following accusations by her deceased husband’s relatives that she had “killed him with an overdose of sex.”

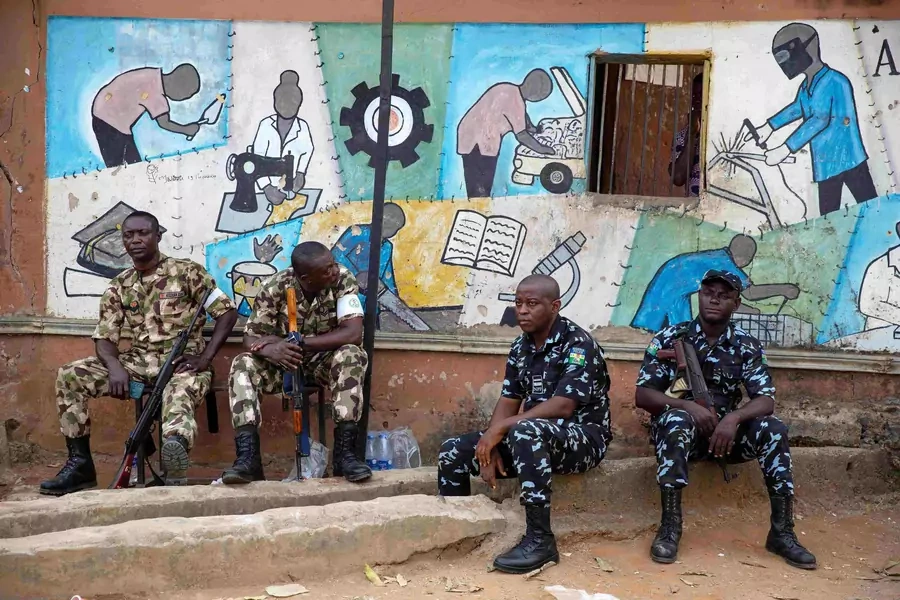

But it is not members of the public alone who regularly take the law into their own hands. It is not unusual for personal disputes involving police officers and soldiers to be settled by a recourse to fisticuffs, while police officers and soldiers have been known to casually shoot members of the public deemed to have rubbed them the wrong way. In March last year, the Lagos State Police Command dismissed Inspector Jonathan Kampani for allegedly firing at and killing one Jelili Bakare. Last Christmas, Bolanle Raheem, a Lagos-based property lawyer and realtor was killed after assistant superintendent of police Drambi Vandi fired at Ms. Raheem’s car at a police checkpoint in Lagos. While Mr. Vandi is currently standing trial on a one-count charge of murder, most cases of officer-involved shooting often go unreported, never mind being prosecuted.

Frustration at persistent law-breaking and disregard for human life by law enforcement instigated the October 2020 monthlong #EndSARS protests.

At the same time, civilian violence against law enforcement, often in retaliation, is not uncommon. Last week, Seun Kuti, forty, the youngest son of the late Afrobeat legend, Fela Kuti, was caught on video shouting at and apparently assaulting a police officer after an altercation. Mr. Kuti has been placed under arrest. In September last year, the Force Public Relations Officer, Chief Superintendent of Police (CSP) Olumuyiwa Adejobi had to react after a recording circulated of some individuals apparently assaulting and attempting to disarm a police officer.

The reasons for this epidemic of lawlessness are not far-fetched. The prevailing, and perhaps understandable, sentiment about justice among a cross section of the Nigerian public is that it is only available to the highest bidder, and that certain people, including but not necessarily limited to powerful members of the political elite, are more or less above the law. Following the recent trial and conviction by a UK court of former Deputy President of the Nigerian Senate Ike Ekweremadu and his wife, Beatrice, for organ-trafficking, many Nigerians wryly noted that no such trial of a political bigwig could have happened in Nigeria. On the contrary, most are convinced that the involvement of law enforcement or the judicial system in any controversy, especially those involving people with the right “connections,” is the surest guarantee that justice will be miscarried. It is not difficult to see how this encourages ordinary people to take the law into their own hands, often times by dispensing summary justice. The fact that some 150,000 of a total workforce of 400,000 police officers are attached to various “big men” and sundry private entities validates public perception that the police exist to protect those rich enough to privatize violence and terrorize the poor who are not.

Unsurprisingly, recent polling on popular perceptions of governance corroborates the existence of a high level of public mistrust of the police and the judicial system. A 2021 survey by Anvarie Tech, Researcher NG, and Bincika Insights showed that “about 71 percent of Nigerians lack trust in the judicial system.” Similarly, more than 70 percent of Nigerians do not trust the police, while 73 percent believe “most” or “all” police are corrupt. A legitimate inference from the many incidents involving them is that even law enforcement officers have little confidence in the law they theoretically uphold.

Typically, policy conversations on violence in Nigeria have focused on spectacular acts of violence like the Islamist insurgency, banditry, and persistent waves of kidnapping. While this is justified, it goes without saying that everyday lawlessness, signaling as it does a radical lack of faith in the state and its security and legal apparatuses, is, in the final analysis, more corrosive to the social fabric. For the incoming Bola Tinubu administration to have any chance of success, it must develop a strategy to repair police-public relations with the aim of restoring law and order. Also, it must invest in practical and symbolic initiatives with the determination to strengthen belief in the judiciary as an institution and instill confidence in the rule of law more broadly.

The current situation in Nigeria is just one extrajudicial killing shy of full-blown anarchy. The urgency of curtailing it cannot be overstated.