As the crisis in Sudan intensifies despite truces and ceasefires, many regional interests are at stake — and under threat. So who is backing who in Africa’s third-biggest nation? DW takes a look.

The conflict in Sudan has seen two generals, Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and Mohammed Hamdan Dagalo, fight for control over Africa’s third-largest country and its vast resources.

Analysts believe the relationship between the warring men is so bad that fighting will only cease when one has defeated the other.

Al-Burhan leads the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) — while Dagalo, better known as Hemedti, controls the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) paramilitary group.

The pair united to oust strongman President Omar al-Bashir in 2019, and briefly rode a wave of popular support — as it seemed to Western eyes at least — that Sudan was taking tentative steps towards democracy.

This hope evaporated when Abdel Fattah al-Burhan dissolved the Transitional Sovereignty Council in 2021.

Conflicting, crosscutting, converging alliances

Now, as Sudan descends further into conflict, there is plenty at stake for its regional neighbors.

Yet, as former Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok said: “This is not a war between an army and small rebellion. It is almost like two armies — well-trained and well-armed.”

RSF fighters, thought to number around 100,000, are loyal to Hemedti and have bases across Sudan.

The true picture of their allies is murky, but tends to include Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar’s forces in Libya, and Russia’s Wagner private military company.

The RSF is also believed to have good relations with Yemen, as Hemedti sent thousands of RSF mercenaries there to fight Iran-aligned Houthi fighters, allying with Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

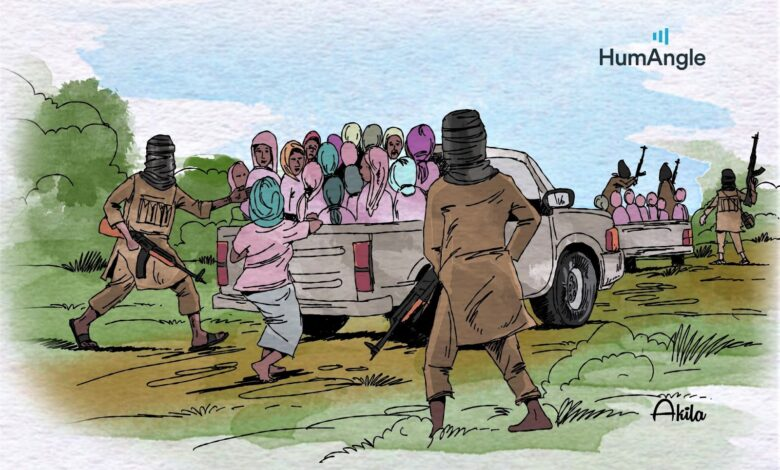

The RSF does not have the same military hardware of the army, such as an air force. But the militia is highly mobile and experienced in using hundreds of so-called technicals.

These are mostly Toyota Land Cruiser and Hilux 4×4 pickup trucks mounted with machine guns, anti-tank weapons, rocket launchers and small arms. They are well-suited for remote desert patrols and urban fighting, effectively diminishing the SAF’s artillery and air superiority.

Many of the technicals were acquired in Dubai, according to a Global Witness investigation.

Additionally, the Russian paramilitary group Wagner has been rumored supply weapons to the RSF in exchange for RSF-controlled gold mining resources.

Russia has long sought to establish a naval base in Sudan, and both Hemedti and al-Burhan have courted Russian interest in building infrastructure. In fact, former President al-Bashir in 2017 pitched Sudan as “Russia’s key to Africa.”

Power dynamics

Regionally, Hemedti has allies in Chad, according to Ahmed Soliman of Chatham House, an expert on Sudanese security.

“You have connections here with Darfur being the heartland of the Rapid Support Forces, with Hemedti having roots within Chad, being from the Arab Rizeigat community that spans Chad and Darfur, and having family members within the Chadian Transitional Military Council,” Soliman told DW.

Researcher and Sudan expert Aly Verjee from the School of Global Studies in Gothenburg, Sweden, cautioned against oversimplifying the power dynamics of the Rizeigat community, which spans the fluid border of Sudan and Chad.

“There’s lots of tensions within these groups,” Verjee pointed out. “There’s lots of sub-divisions as well. More importantly, Hemedti has been successful in a way that others have not: in branching out and recruiting to his forces from across Sudan.”

While the RSF may have grown out of the Janjaweed militias active in Darfur decades ago, the fighters today are younger and much more diverse, Verjee added.

Matters are complicated by instability and disputes along Sudan’s border.

In the last decade alone, South Sudan, Libya, Chad and Ethiopia have experienced armed conflict. For instance, Ethiopia shares a disputed border with Sudan, known as the Al-Fashaga District.

“Ethiopia would not want to pick up another war with Sudan, but if the ongoing crisis can help it gain some advantage at a negotiating table later on, then Ethiopia may be tempted to make certain moves,” said Hassan Khannenje, director of the Horn International Institute for Strategic Studies.

“At this stage though, there’s no evidence that they are supporting any of the leading groups. Ethiopia will have an interest in working with a civilian administration that is a little bit more understanding of its own.”

Sudan is ‘its own quartermaster’

The SAF, or regular army — which numbers around 120,000 personnel excluding reservists — has deep ties with Egypt.

Egypt, meanwhile, must balance its support for al-Burhan’s forces with its dependence on investments from the UAE, which support the RSF.

Another major Gulf player, Saudi Arabia, has supported both the RSF and the Army.

However, Verjee believes international actors from the Gulf and further abroad may have overstated their influence on the fighting.

“The decision to escalate in this way, they [al-Burhan and Hemedti] had to know that would be received very badly, and yet they did it anyway,” he told DW, adding that internationally brokered ceasefires have been routinely ignored.

“The internal calculus is much more important than what anyone says from outside,” he continued, saying Sudan has always been its own “quartermaster” and that historical conflict in Sudan has relied on local people to sustain its fighting ability, rather than counting on outside influence.

Khannenje believes allies of both the RSF and SAF will try to convince both parties to pursue peace talks.

But in the absence of dialogue, he fears that “in the next one, two, three weeks, then suddenly you’re going to see that the allies outside Sudan start channeling in both money and weapons,” he told DW.