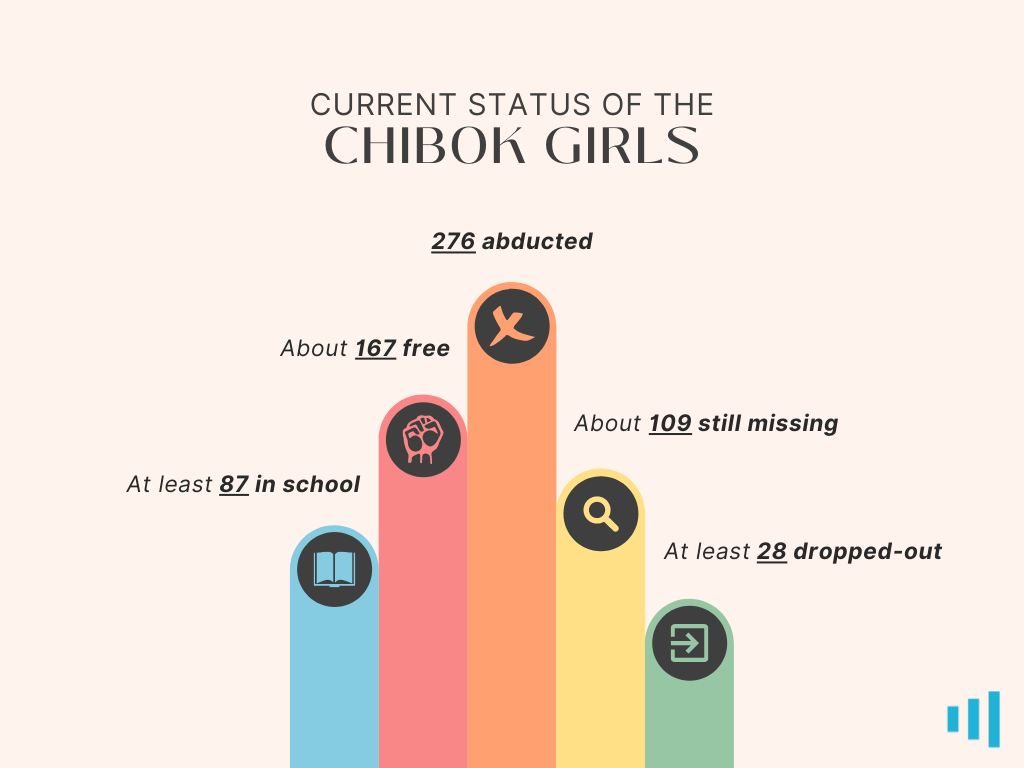

Two hundred and seventy-six girls were kidnapped. Among them, over 100 are still missing. But, also, well over a hundred either escaped or were released by their captors. How are they faring?

Over the course of two days, nine girls converge in a tiny hotel room in Yola. As a group, they are some of Nigeria’s most popular young women. Their names and faces have appeared on large billboards, in newspapers, and on international news channels. Their cause has been championed by the world’s upper crust. Several books have been written about them. There’s even an advocacy group dedicated exclusively to ensuring their safety and wellbeing. But, right here in the tiny hotel room, with most of them wearing dull-coloured ankara dresses and slippers, the nine girls from Chibok could not appear more ordinary.

The conversation takes on different forms. Awkward silence. Reluctant complaints. Laughter. Cautious appeals. Awkward silence. Dreadful flashbacks. Bold pronouncements. Gratitude. Expressions of doubt. Expressions of hope. Awkward silence.

The girls, who are in Adamawa, Northeast Nigeria, are miles away from home. They had taken a break from schoolwork at the American University of Nigeria (AUN) to reflect on what life has been like since regaining freedom five years ago.

Their story is one that’s been told and retold countless times. On the night of April 14, 2014, 276 students of the Government Girls Secondary School in Chibok, southern Borno State, were seized from their dormitories and taken prisoner by terrorists. It was not a planned abduction. Mustapha Chad, the Boko Haram commander who orchestrated it, had unsuccessfully tried to lead an attack on the Nigerian Air Force (NAF) base in Yola and had taken the girls on the way back merely as an afterthought.

The news soon went viral. It broke the internet and broke the heart of the international community. It also launched the terror group into the limelight, the late leader Abubakar Shekau milking the opportunity as much as he could. “Just because we kidnapped these young girls, you are making noise?” Shekau had asked in one of several statements, where he’d also threatened to sell them as slaves. Those who refused to marry his followers were truly used as slaves to break stones, fell trees, build thatch houses, do laundry, and engaged in other hard labour. Anyone who tried to run was whipped, tied up, and denied food.

Over 50 of the girls escaped soon after the abduction by jumping from the trucks. About four others escaped later in the year of the attack. In May 2016, one girl slipped away with a child and a member of the insurgent group whom she called ‘husband’. The following October, 21 were released after negotiations with the Nigerian government. Then, in 2017, the group released 82 more girls after receiving a hefty ransom and some previously imprisoned associates.

The nine girls in the tiny hotel room are part of the batch of 82.

After their release in the wee hours of May 7, 2017, they spent eight months in Abuja for a rehabilitation programme that saw them learning vocational skills and receiving medical care. Subsequently, the government enrolled them at the American University of Nigeria, a private institution in Yola, for a pre-degree programme. This took nearly four years. In 2021, many of them finally became undergraduates at the same school.

The Nigerian government said it placed 106 of the girls on scholarships at AUN. Some who escaped in 2014 received sponsorship from the university itself. HumAngle understands that about 10 Chibok girls are also studying in the United States, including three who are in postgraduate school.

Shortcomings

After watching interviews granted by girls who regained freedom, one question featured prominently in the public’s reaction: Why are they not communicating in English, Nigeria’s official language, despite being final-year secondary school students? Several answers have been offered, from poor quality of teachers to the students preferring to speak their local dialect even in the classroom. One of the girls explained in 2017 that, because teachers often failed to show up, the students would pass time sewing or braiding their hair.

The ripple effects of this poor educational background are felt up to now. Despite the years spent in a pre-degree programme, there is still a world of difference between the Chibok girls at AUN and other undergraduates. But there are other reasons the girls are struggling to catch up. One is the lack of adequate funding.

The government’s scholarship programme takes care of tuition, accommodation, and feeding. The girls are also paid a monthly allowance of ₦25,000 (previously ₦8,000). Between 2017 and 2019, tailors took their measurements and gave them each one dress per year. That is all, they told HumAngle. The girls’ other essential needs such as books and levies charged by student associations are not covered.

“I talked to one of our mentors about the books countless times, but I didn’t get them and had to use my money,” says Rebecca, 24, a law student. She adds that, sometimes, she feels like switching to a different course because of the financial burden.

The last book she bought cost ₦6,500. Whenever she cannot afford recommended texts, she copes by borrowing copies from the library for a few days.

Even though the allowance is hardly enough considering fast-rising inflation and though some of them rely on additional money from guardians, their townspeople often assume they are rich. They tend to call them “children of government” or “Buhari’s daughters” each time they go home, and the girls find it awkward.

Another challenge is the lack of reliable personal computers. During their stay in Abuja, the government gave them made-in-Nigeria AfriOne tablets, which many say only lasted for a year or two. One philanthropist also gave them laptops but a lot of them have either developed faults or are too slow to meet their academic demands. Sometimes, they stop working abruptly during class quizzes and the owner is scored zero. Assignments at AUN are submitted online and students are regularly tested using Canvas, an e-learning platform. And so participation can be frustrating without reliable computers.

“Since last semester, my laptop has had a motherboard issue,” complains Jummai, 25. “It’s not only me. Let me say all of us because our laptops are not as good as other people’s laptops. And without good laptops, you can’t perform well. They will send assignments through Canvas and our phones will not be able to do it.”

Jummai was told it would cost ₦45,000 to fix the problem but she does not have such an amount. As a student of Communication and Multimedia Design, she especially needs a personal computer to get her tasks done. “I passed three courses and failed one last semester,” she notes. “I think if I had a laptop, that wouldn’t have happened.”

Complaints to the mentor assigned to them about this problem have yielded no results. “He said that he is working on it, that he is complaining to the government, and that we should be patient,” recalls Rebecca, tugging at her hair.

The programme is, in some ways, implemented without sufficient consideration of what the girls truly want. Some of them like Esther and Blessing are passionate about becoming nurses after graduation. But because AUN has no Nursing department, they were sent off to the Natural Environmental Science (NES) department instead. It is not certain if the government has plans to sponsor their enrolment in nursing school after the first degree.

HumAgnle learnt of another girl who dropped out for a similar reason: she wanted to study Medicine, a course that is not available at the school. She is now preparing to get married.

The choice of university itself is controversial. Some of the girls have disliked the idea of attending AUN from the outset and say their protests to the women affairs ministry were ignored. Others do not like that there are so many Chibok girls in the same school, especially since many of them have been together through primary school, through secondary school, through captivity, through rehabilitation, and through the pre-degree programme.

Their segregation in school has made matters worse. They argue that spending so much time together does not help their academic performance. They end up speaking Kibaku and Hausa among themselves, rather than improving their grasp of English.

Dr Allen Manasseh, an activist from Chibok who has interacted closely with the girls, lends his support. “The greatest form of learning is not even in the classroom, it is in the process of interaction,” he says. “Especially for them, what they were expecting was to interact with people from diverse backgrounds, to encourage and motivate them, and that is the standard. That interaction with students from different cultures will even support them psychosocially which is part of the rehabilitation.”

The girls suspect learning in a diverse, non-judgmental environment could be what has made all the difference for former abductees who had a chance to study abroad and whose spoken English has improved a great deal. They also think if they are distributed across different schools, they will be forced to mingle with other students, which could make them more eloquent.

From the authorities’ point of view though, keeping the girls together in the same school will likely protect them from loneliness and help them to “feel at home”.

How wonderful it would be if all school-related problems ended with semester examinations. But for the Chibok girls, during the holiday, they still worry that they are not investing enough time into their studies. They are desperate to narrow the gap between them and other students. But back in their respective villages, they are faced with conditions that force them to abandon their books. They have to help on the farms and in the kitchen during day time. At night when they are free, it is usually too dark to read as there is no electricity supply.

The girls say they’d prefer to spend their holidays in places where they would be able to focus. Some of them have relatives in other states but usually do not have enough money to transport themselves when it’s time.

“That is why we want the programme to be open so that other organisations can come in to support them,” says Dr Manasseh. “They won’t be having these small challenges of money and other needs. If they decide they want to do their masters, some other people will commit to helping. And for those who need extra improvement during breaks like this, they may decide to send them to summer school somewhere. They can spend that time learning and then come back better … Besides, if you ask for help, 1,001 people can bring computers for them.”

Perhaps the biggest challenge is not that they have several unaddressed problems but that there is no effective means of contacting their benefactors. Mary, 21, observes that whenever they meet their appointed mentor, “he will say even if he is calling those who are in Abuja, they are not even picking his call. We don’t know what all that is about.”

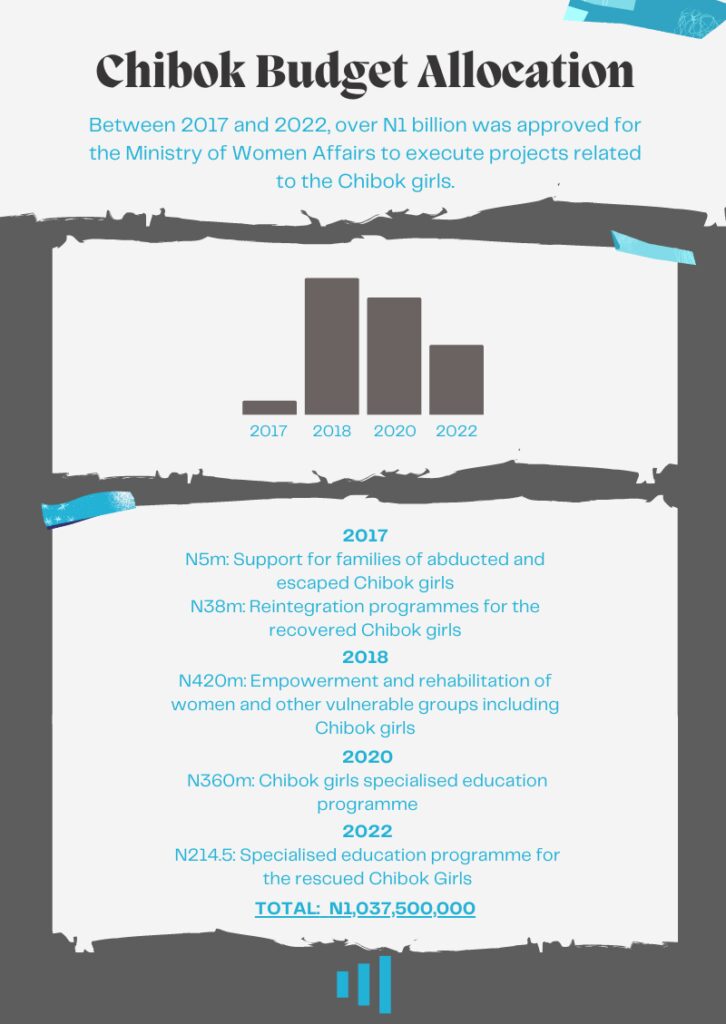

Between 2017 and this year, about ₦1 billion was approved for the Federal Ministry of Women Affairs to support families of the Chibok girls as well as cater to the girls’ reintegration, empowerment, and education. In 2016, ₦13 million had also been allocated to the ministry to support unspecified “families in distress” and some money has gone into monitoring projects related to the girls.

A search through the ministry’s website and social media accounts (Facebook and Twitter), however, returned no results related to the Chibok girls or how the monies disbursed have been spent. But information from AUN is helpful.

In 2014, the university said the pre-degree programme cost $5,000 per year for each girl while the college programme cost $12,000. It estimated that it would need $3,074,000 to educate 58 girls for five years.

Information on the school’s website also indicates that it costs at least between ₦2.5 million and ₦4 million to pay for an undergraduate’s annual tuition, housing, and meal plan. This means it likely costs between ₦185 million and ₦296 million to pay the fees for the about 74 Chibok girls now attending the school. The monthly allowances alone should sum up to about ₦22.2 million a year.

Outcasts

The American University of Nigeria often takes a front-row seat in any ranking of the most expensive universities in the country, sometimes assuming the first or second position. Naturally, it attracts undergraduates from the privileged class. And for girls who have lived in rural Chibok all their lives, fitting in seems hopeless. They feel like black sheep, like all they have is themselves. There is always an ‘us’ versus ‘them’ dynamic — us being children from modest backgrounds who can only attend through a scholarship and them being young men and women sponsored by their parents.

“When they hear you are Chibok girls, you are on your own. They don’t want to talk to us. They don’t want to socialise with us,” says Falta, before hissing lightly and sighing. “We are passing through a lot, seriously. We are not happy about it. They are looking at us as if we are animals, like we are not human beings sef. The way the students and some other lecturers are treating us; we are even feeling frustrated.”

The discrimination is such that when other students realise they have been assigned to the same rooms as Chibok girls, they request to be moved elsewhere.

Lecturers at the school have not been beacons of social inclusion either. They are said to use derogatory terms in describing the girls, such as saying “there are people from poor backgrounds among us” or suggesting they are less smart. Because of this, participating in class is hindered by crippling anxiety. One time, a girl stormed out of a lecture room in tears and thought of quitting school after an instructor insulted her. Some of the girls say if they had been in her shoes they would have definitely dropped out.

Hannatu, 24, is one of many who gave a thought to quitting school earlier this year.

“It is just that the discrimination is too much and that is making us discouraged,” she explains. “When we come to class, the instructors look at us as if we are bad people. They don’t want to talk to us. Even if we give them an answer, it is not appreciated. Sometimes, my sisters are crying, complaining about the school. We are feeling as if we are still at that bush [terror enclave] sef, sometimes, [because of] the way they are treating us.”

She adds that the discrimination they face is one of the reasons they still are not able to speak flawless English since they only have themselves to chat with. And when they are with others, they are extra careful so as not to be made a mockery of.

If she had enough money, Hannatu says asides helping her parents and enjoying her life, she would buy ‘good good … expensive things’ such as a phone, laptop, and clothes. Maybe then the students and instructors would admire her and maybe in that admiration, there would be some respect as well.

“Expensive clothes that you will wear and someone will say, ah…” Her face and those of the other girls light up as if in a daydream.

HumAngle contacted Daniel C. Okereke, AUN’s Executive Director of Marketing and Communications, about the complaints but he replied that only the women affairs ministry can comment “on any issues concerning the education of the Chibok Girls”.

Shehu Maikai, who was until recently the ministry’s press director, however, said he had retired from service but did not respond to a message asking for his successor’s contact. Also, an enquiry submitted through the ministry’s website is yet to be acknowledged.

The other Chibok girls

While a lot has been said about the Chibok girls who returned safely, there is another set of children who have been ignored: those given birth to during the abduction. At least three of the girls came back with babies between 2016 and 2017. One of them was Rose, 24.

She says the government promised to take care of her and her child after her escape, but “now they send us to school and they made us send the children to our parents.”

This arrangement is tough because her father is late and her mother is too old to adequately fend for the family. She has to deduct from her monthly allowances to pay for her daughter’s nursery school fees. When the allowance was still ₦8,000, she would send ₦5,000 out of it every school term, and then find other ways to take care of herself. Now, the little girl’s school fee is ₦7,000 and she still has to buy textbooks alongside other items.

“When the minister came to visit us, she said that she doesn’t know anything about our children but she will try her best. Then up to now, we’ve not heard from her.”

Rose’s daughter faces discrimination too. She hears stories about how her mom was abducted. Last February, during a phone conversation between mother and child, the latter mentioned that on her way to school, some people told her she did not have a father.

“I don’t feel happy,” Rose says. “And it affects my studying because I’m always thinking and can’t concentrate properly.” If she had the means, she would have transferred her daughter to a different community where she can grow up without stigma. Now, even though she has relatives in other cities, she cannot burden them without at least contributing to her upkeep.

“We want them to stay somewhere aside from Chibok so that they will grow up with a good educational background and they will not suffer like the way we are suffering to catch up.”

Dr Manasseh says about her situation that the government has no excuse not to provide for the child’s sustenance since the mother became pregnant while in captivity. “It is the government’s negligence that got them abducted; it is the government’s negligence that failed to rescue them; so government must take the responsibility,” he argues.

In spite of the struggle to pay her fees at this level, Rose wants her daughter to become a university graduate someday. “I want her to be educated,” she says with a firm tone as she leans forward. “So, people can say, yes, all this happened to her but she didn’t give up, and her daughter is in a good position.”

Dropping out

The Chibok girls have come to be seen as embodying the right to education. So, there’s pressure to ensure that they themselves attain high levels of training. But coming from a community where few girls get basic education, let alone attend university, it does not always work out.

Data obtained by HumAngle shows that about 28 of the released girls have left school, out of which 16 are married, three are set to wed, and one had previously been married. Two of those who dropped out are said to be among those in the United States.

While some quit school after getting married, others simply could not stand the rigour and discrimination that came with the school environment.

“Some of our instructors are saying that we are not trying at all. But we are trying, we are not sitting like that. We are trying our best, struggling to make sure that we make it. Instead of encouraging us, they are discouraging us,” explains Rose. “Then some of us feel like, ‘I am trying my best and then someone is still discouraging me; let me give up and just go and do what I’ll do.’ That’s what made others drop out of school.”

One girl got pregnant right after the pre-degree programme and has since not shown up at the university. Others were not comfortable with the rules set for them at the school. There was also the concern about time. The girls were not getting younger and they saw the pre-degree programme as protracted.

Some of those still in school are thinking along a similar line too.

“The school is not bad. But before I finish, I think I will be … with white hair,” Mary chuckles. “I will become a grandma. Before we got admission, we have spent three years and some months in the pre-degree programme and just now I am entering university… I think I will not finish the school, but I will try my best.”

The girls ask the government to not abandon those who have left school, suggesting that they can still be supported with business grants or other forms of assistance.

“Nobody cares enough about them to say, ah ah, these people are no longer in school, maybe they can help them in some other ways,” a tired-looking Mary wonders. “They are just at home without anybody asking about them.”

Many of the Chibok girls who have chosen to continue schooling are driven by grand ambitions. Rebecca, for example, had always wanted to become a doctor. Along the line, she started seeing how the rich bullied the poor in her community. In one case, someone who was like family to her lost a claim to his land because he could not afford litigation. Rebecca was convinced she needed to stand up for people like him and saw law practice as the way to do this.

Hannatu is studying International Relations because she sees herself representing Nigeria on the global stage someday, addressing topics dear to her heart like how bribery and corruption inhibit national growth.

For Falta, who is an accounting student, she opted for the course because accountants are rumoured to be well-paid. “I want to make that money so that I can take care of myself and my family,” she says, smiling.

Priorities!

The girls have a lot they want to say to the government, things they wish to ask for, and a lot to worry about. But their greatest concerns are obvious: the return of peace to their communities and the return of their schoolmates still held captive from the bush.

“I’m still praying and I want the government to please … that place is horrible, it is … it’s not good at all,” pleads Rebecca. “I want them to try to bring my sisters back home. I want them to come back and experience this beautiful world.”

She likens the conditions of abduction to “the pit,” referring to hell. There is no electricity or good food and, when they lived there, they had to drink water from the ground. “The place is not good for them.”

Others say the same thing. They want their colleagues to be as free as they are now, and they are worried the government has been too silent about what it is doing to rescue them.

Yana Galang, 65, is one of the parents still keeping hope alive. She rejoiced as others reunited with their children and anticipates the day people will also celebrate with her after Rifkatu returns.

“It is remaining small time for Mr President, Buhari, to leave the office. And he promised us he would bring the girls for us, all of them. So, we don’t know; we want to ask him: is it this small time that remains he is going to bring our girls or is he going to leave the office without bringing them?” she tells HumAngle during a phone interview.

Another common concern among the girls is that the communities in Chibok remain unsafe. Between January and March this year, there have been at least three violent attacks in the area. According to reports catalogued by the Nigeria Security Tracker, those attacks led to the killing of nine people and the abduction of 27 others, mostly girls.

It devastates Mary whenever she reads reports of yet another attack or when she speaks to the people at home and they mention them. “How can government help Chibok to be safe?” she asks. “Sometimes when I hear some bad news, most especially in connection with Boko Haram, I will be thinking that so this thing will not be finished from this community.”

Her village, Makalama, is now deserted as the inhabitants, several hundreds of them at least, have moved to areas such as Mbalala, another town in Chibok, and Askira due to insecurity. People are generally afraid to farm, travel, or even sleep in their houses.

When they visit home, the Chibok girls come face to face with the life-threatening reality.

“Sometimes, at the night ma sef, you can’t even sleep. You even sleep with your shoes on because if they say let’s run, you have to run. Some of our parents are not able to sleep comfortably because these people are still attacking them,” narrates Blessing.

Falta has one other issue that burdens her heart. Each time she travels home for the holiday, the parents of some of her former colleagues meet her to ask about their children. “God will bring them back,” she would reply. But they are not alive and she knows.

They had given the government the names of their mates who died in captivity. The government had replied that they should not mention it to anyone else. But it troubles her, this secret.

“Three out of the six people from my village, Mifa, died there and their parents are asking us that ‘what about our daughters?’” she says. “Sometimes, I am confused. I don’t know what to say. I am telling them that God will bring them back, but they are not alive. It is a sin, seriously.”

HumAngle learnt that not many are alive among those unaccounted for and that most of those who are still with Boko Haram have become radicalised. The causes of death range from childbirth to bomb explosions. Multiple sources within the insurgency told us that oftentimes when Nigeria’s Air Force bombarded the terror hideouts, some Chibok girls would run in the opposite direction and try to draw the pilots’ attention, perhaps hoping they would be rescued. Instead, bombs were dropped on them.

Meanwhile, the girls think they can benefit from more show of concern. At the moment, says Mary, it feels like nobody cares about them or whether they are doing okay.

One thing the girls and the world need to realise, notes Dr Manasseh, is that their education is not for their personal benefit alone. Introducing over a hundred female university graduates to Chibok will trigger widespread development. “People are even scared about the transformation that will come once these guys graduate and move back to that community,” he stresses.

In the months following April 2014, a group of teenage girls huddled together in a place that was part of Nigeria, yet so distant and different from home. The terrorists considered them stubborn, much more stubborn than the schoolgirls from Dapchi who would be abducted in a similar fashion four years later. Many who were non-Muslims openly refused to convert to the religion the terrorists professed.

The girls would be told over and over that schooling was haram, ‘especially for ladies’. That they ought to dedicate themselves to God and their husbands. When the abductors made preparations to release them, they warned that if they returned to school they would visit and kidnap them again. It wouldn’t matter that they had travelled ‘as far as Switzerland’. Many of the girls panicked and resolved to avoid school like the plague—‘even if it was in front of my father’s house,’ one of them used to say. Another girl thought that there was no way she would return to the same school system that had put her through so much suffering.

Most of them have now overcome this fear. Some know exactly what they want to do after getting their degree. It could be as lofty as addressing the United Nations General Assembly and transforming the Chibok community or as simple as getting a job, moving on, and trying to forget all that’s happened. Others, at this point, just want to get through school. The future can wait.

“When we were rescued, the time that I was in Abuja, I said that I would not go to school again,” recalls Falta. “But now I am in school and I will become what I want to become. One day, I will achieve my dreams by God’s grace.”