- The United States provided training to several West African military officers who later went on to be involved in at least nine coup attempts in five countries since 2008.

- Russia may integrate this narrative into overall efforts to undermine the U.S. campaign to convince African governments not to engage further with the Kremlin-linked private military company known as the Wagner Group.

- Like many global powers, the United States has a history of involvement in engaging in the affairs of governments across the African continent, which can serve to further discredit future U.S. involvement.

- Russian influence is increasing in sub-Saharan Africa while simultaneously, European countries are drawing down forces from peacekeeping and counterterrorism operations in Mali.

Since 2008, the United States has trained or funded the training of several African military officers who later went rogue, going on to lead at least nine coup attempts throughout five West African countries. According to a recent report by Rolling Stone, at least eight of these coup attempts succeeded. The new report comes as the Biden administration has grown increasingly aggressive in countering Kremlin-linked private military companies (PMCs) – particularly the Wagner Group – while raising the alarm with allies about their destabilizing influence and alleged war crimes on the continent.

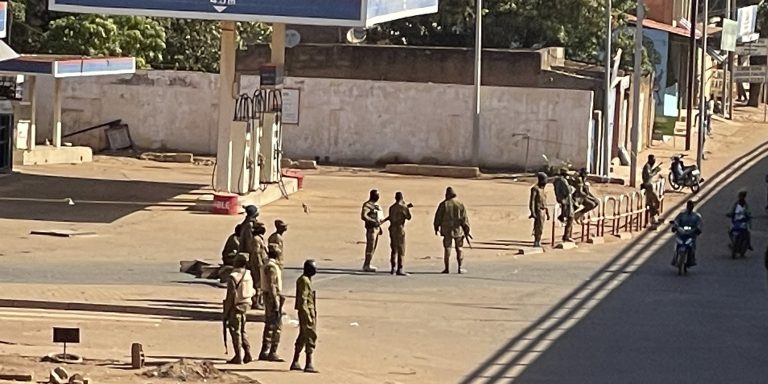

These African military officers attempted to overthrow governments in Burkina Faso and Mali three times, respectively, and once each in Mauritania, Guinea, and the Gambia. The insurrectionists attended a variety of U.S. funded or supported training courses, ranging from military intelligence and special operations trainings to a counterterrorism course held on a U.S. airbase in Florida and an English-language course taught in the U.S. state of Georgia. U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM) states it does not possess data to say how many of its trainees have been involved in subverting African governments, though it did release a statement after the recent September 2022 coup in Mali acknowledging that former Malian army-captain-turned-putschist Ibrahim Traoré had been a beneficiary of U.S. training.

Beyond the report’s demoralizing impact on Africans who want to see stability at a time when the is continent already suffering from issues like terrorist violence, civil war, and food insecurity, the news is likely to undermine U.S. efforts to portray itself and its allies as positive counterweights to Russian and Chinese influence on the continent. Moreover, Russia may integrate this narrative into overall efforts to undermine the U.S. campaign to convince African governments not to engage further with the Kremlin-linked private military company known as the Wagner Group. The U.S. government, not to mention many Western analysts, have made a point of publicly criticizing the Wagner Group as a threat to African stability and security, pointing to the PMC’s support of authoritarian rulers, alleged human rights abuses, and extraction of resources from a number of African states. This criticism has only grown louder following Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine, where Wagner forces constitute a significant component of the Kremlin’s war machine. The PMC plays a role not only on the battlefields of Ukraine but also abroad, as it secures natural resource wealth from the African territories where it operates to help Russia skirt Western sanctions.

However, warnings of Wagner’s destabilizing impact may ring hollow for those who interpret the latest news as an indication that U.S. influence is similarly corrosive. It also seemingly adds to a long history of U.S. engagement throughout the Global South, particularly during its Cold War efforts to contain and counter the Soviet Union and the global communist movement. In Africa alone, the United States was involved in meddling in five countries (Egypt, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Angola, and Chad), variously seeking to secure its preferred leaders, support rebel forces, and at least once, actively engaging in the attempted assassination of a sitting prime minister. More recently, in 2011, a United States-led and UN-supported military intervention ousted Libyan dictator Muammar Gadhafi, producing a power vacuum that dragged the country into nearly a decade of civil war.

The United States is not the only Western power faced with the risk of receding influence or access on the continent. In the last year, the United Kingdom withdrew its troops from the UN’s peacekeeping mission to Mali, while Germany suspended its own participation in the program after the new Malian government refused to grant it overflight rights, announcing it would withdraw German troops from the country by May 2024. More recently, France drew down its own counterterrorism operation to Mali alongside Canada and several EU states per the demands of the country’s latest post-coup ruler and interim president, Colonel Assimi Goïta. Goïta, who previously worked with U.S. special forces focused on counterterrorism and participated in U.S. training exercises, had recalled France’s colonial legacy in the country to demand French forces leave Malian territory while also making room for Russian and Wagner personnel to enter the country in greater numbers.

In light of the many shortcomings associated with the Global War on Terror, the United States has more recently sought to reframe its counterterrorism missions in less stridently militaristic terms. Instead, policymakers have stressed the importance of addressing so-called “root causes” – the social, economic, and civil grievances that can lead civilians to join extremist groups and take up violence against their governments and communities. Nonetheless, the United States still has a substantial military footprint across Africa. While the U.S. military has been reticent to reveal the extent of its involvement on the continent, separate reports published by The Intercept and Yahoo! News and revealed the existence of 29 U.S. military bases in 15 countries and 39 active U.S. military operations across the continent as of 2019, with missions including surveillance, psychological and information operations, logistical support, training African security forces, and countering piracy and terrorism. Additionally, a former head of U.S. special operations in Africa, retired U.S. Army Brigadier General Don Bolduc, said that his forces had engaged in combat in 13 African countries in the four years he served with AFRICOM and the regional branch of the U.S. special forces.

Yet despite these interventions, the Pentagon’s own reporting shows that extremist activity has surged almost entirely unabated in Africa over the past decade, particularly in the Sahel region and the Horn of Africa, especially Somalia. Last year, U.S. President Joe Biden returned around 450 U.S. troops to Somalia in what is meant to be a “persistent” presence in the country moving forward, reversing a decision by former president Donald Trump to withdraw most of the 700 U.S. troops that were stationed there at the time of his presidency. Under Trump, the United States placed more emphasis on conducting air strikes in the region than maintaining a “boots on the ground” presence, though critics say removing U.S. forces emboldened al-Shabaab forces in the country.