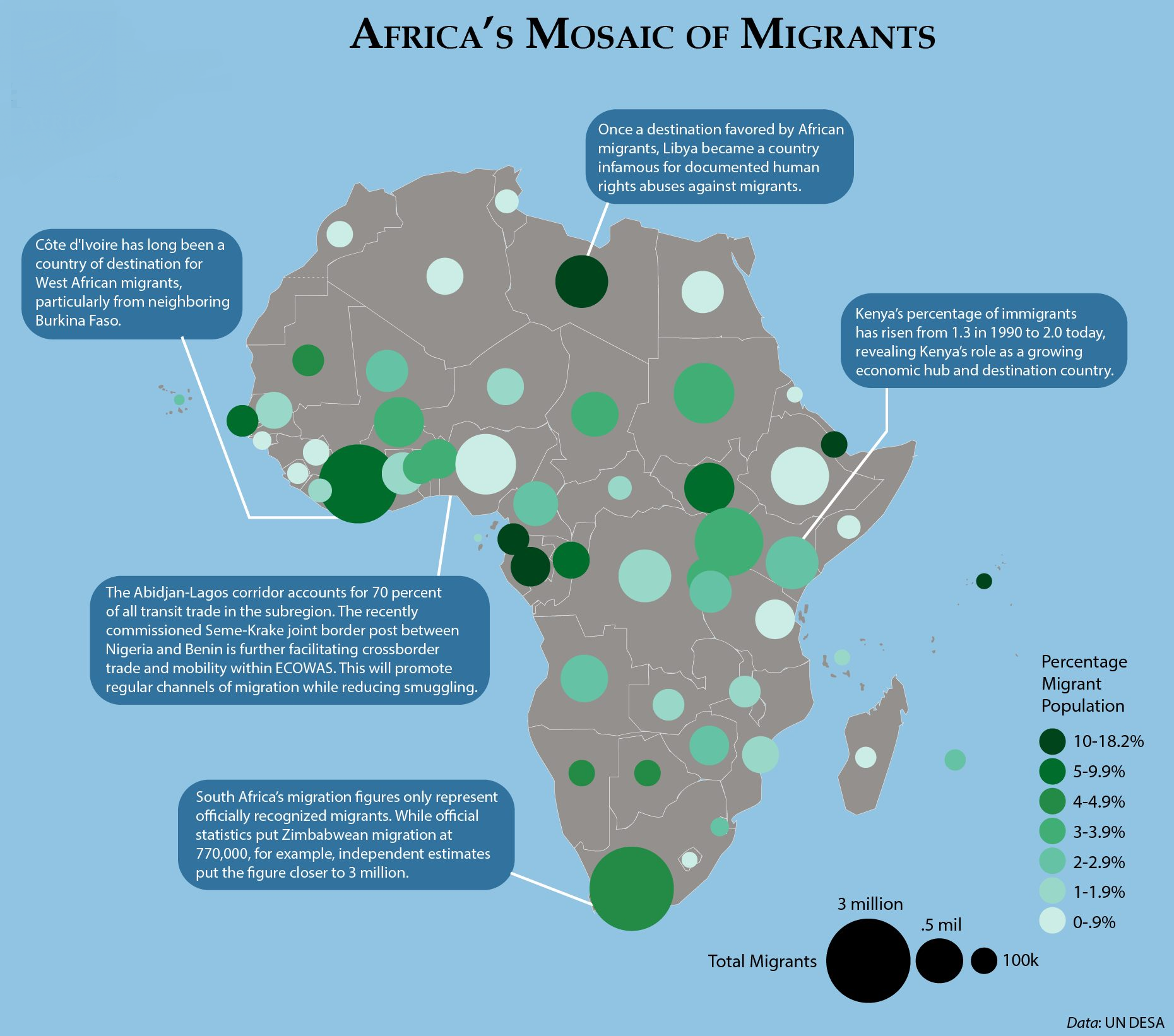

Most African migration is to economic hubs on the continent, a pattern that can be expected to continue as regional economies become more integrated.

African Migration Will Continue to be Dynamic

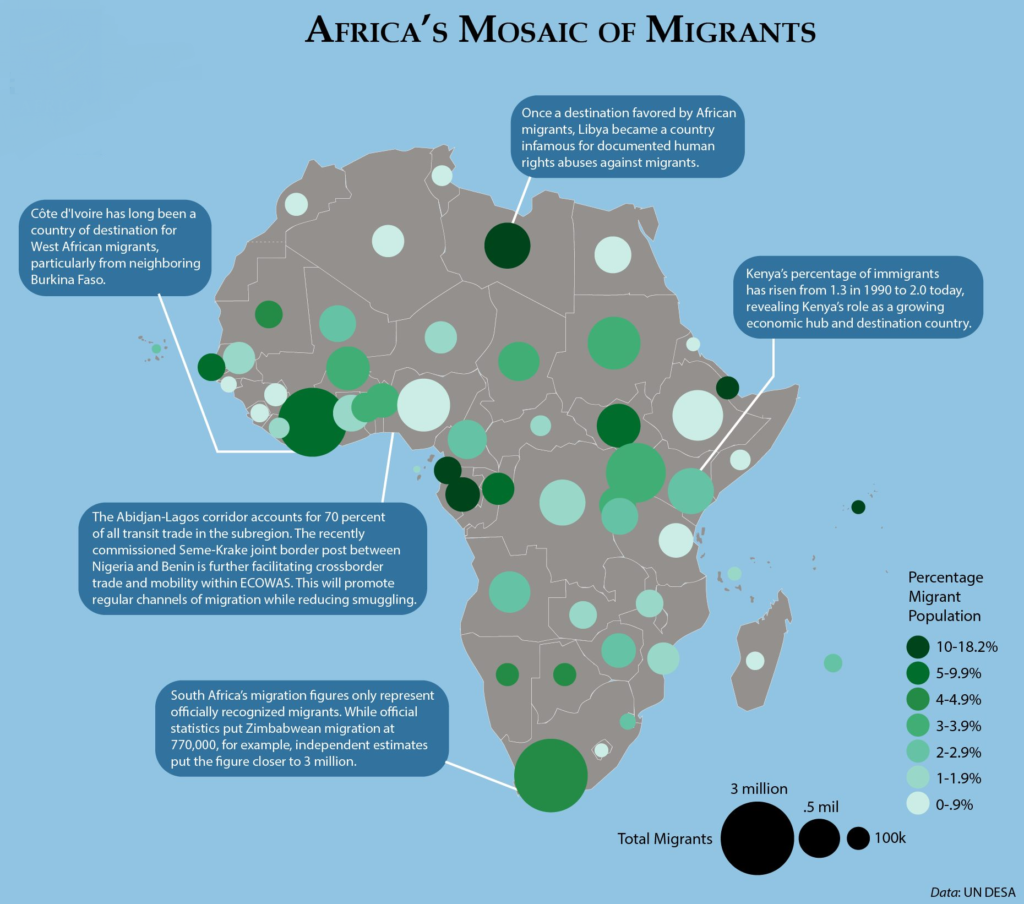

African migration has been on a steady upward trajectory for the past two decades. The record level of over 40 million African migrants represents a 30-percent increase from 2010. Given continuing strong push factors, that trend can be expected to continue in 2023.

While often unrecognized, most African migration occurs within the continent as migrants seek employment opportunities in neighboring regional economic hubs. In fact, 80 percent of African migrants do not have an interest in leaving the continent. Africa accounts for only 14 percent of the global migrant population, compared to 41 percent from Asia and 24 percent from Europe.

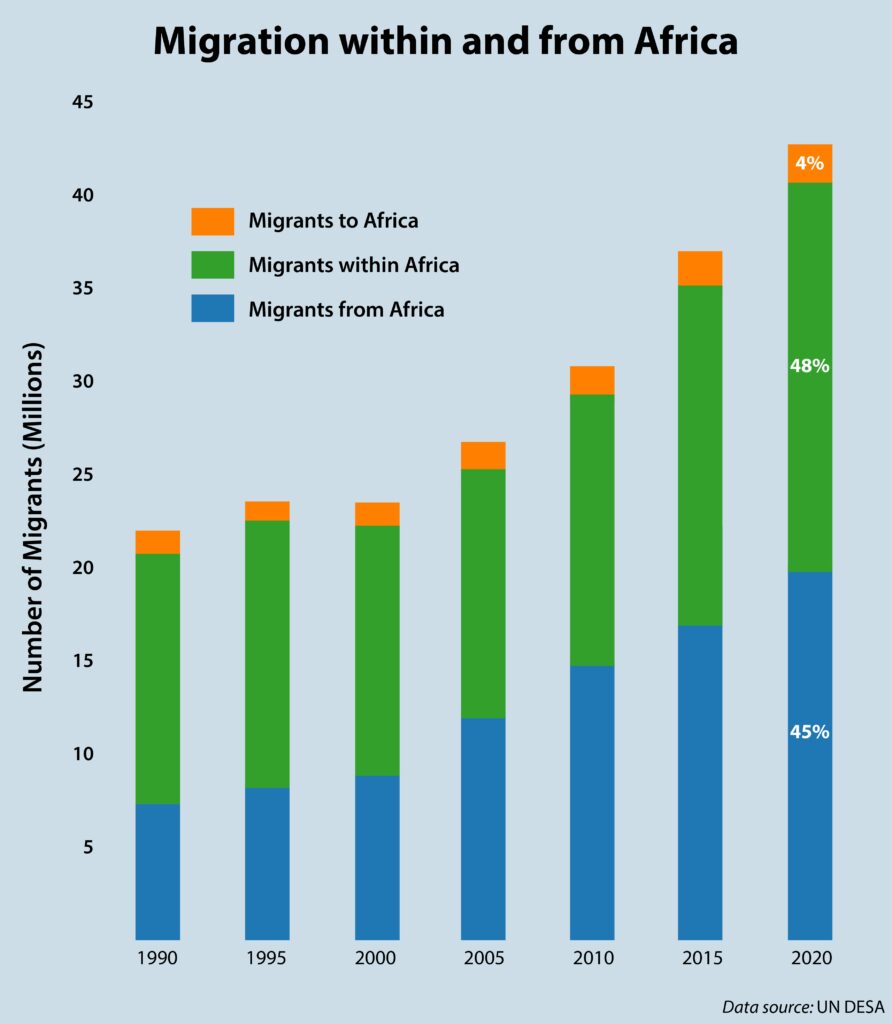

South Africa, Côte d’Ivoire, and Nigeria are among the top five destination countries on the continent, revealing their position as economic hubs for their respective subregions.

With the exception of Côte d’Ivoire, migrants make up less than 5 percent of the population in each of the top destination countries. The majority of migrants in Côte d’Ivoire are from neighboring Burkina Faso, with which it shares common cultural attributes.

Expanding Net Benefits from Migration

Contrary to the conventional narrative, an estimated 85 percent of African migration comprises routine cross border trade and travel. This tangibly contributes to economic stability, the filling of labor gaps, and the socioeconomic wellbeing of destination countries.

Further economic gains from migration will be realized as the Africa Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA) and its Free Movement of People Protocol gain momentum.

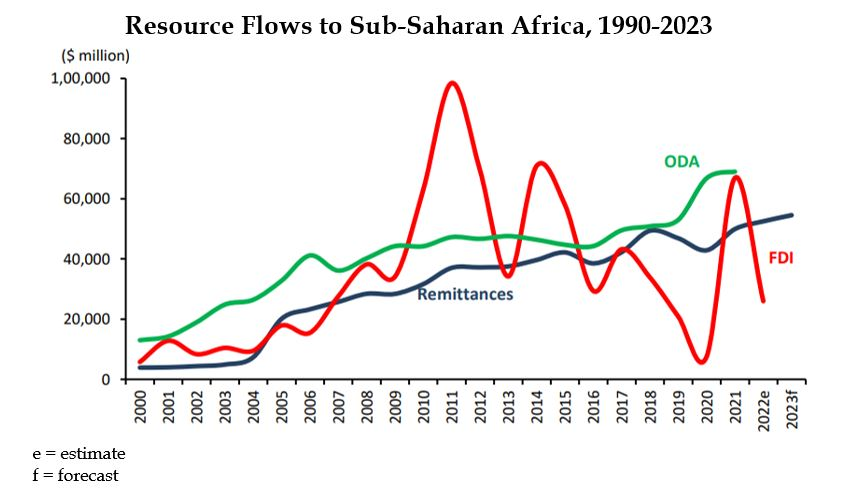

Migration also benefits countries of origin via remittances that contribute to the stability of household incomes in fragile economies, improved food security, and represent an investment education in the next generation.

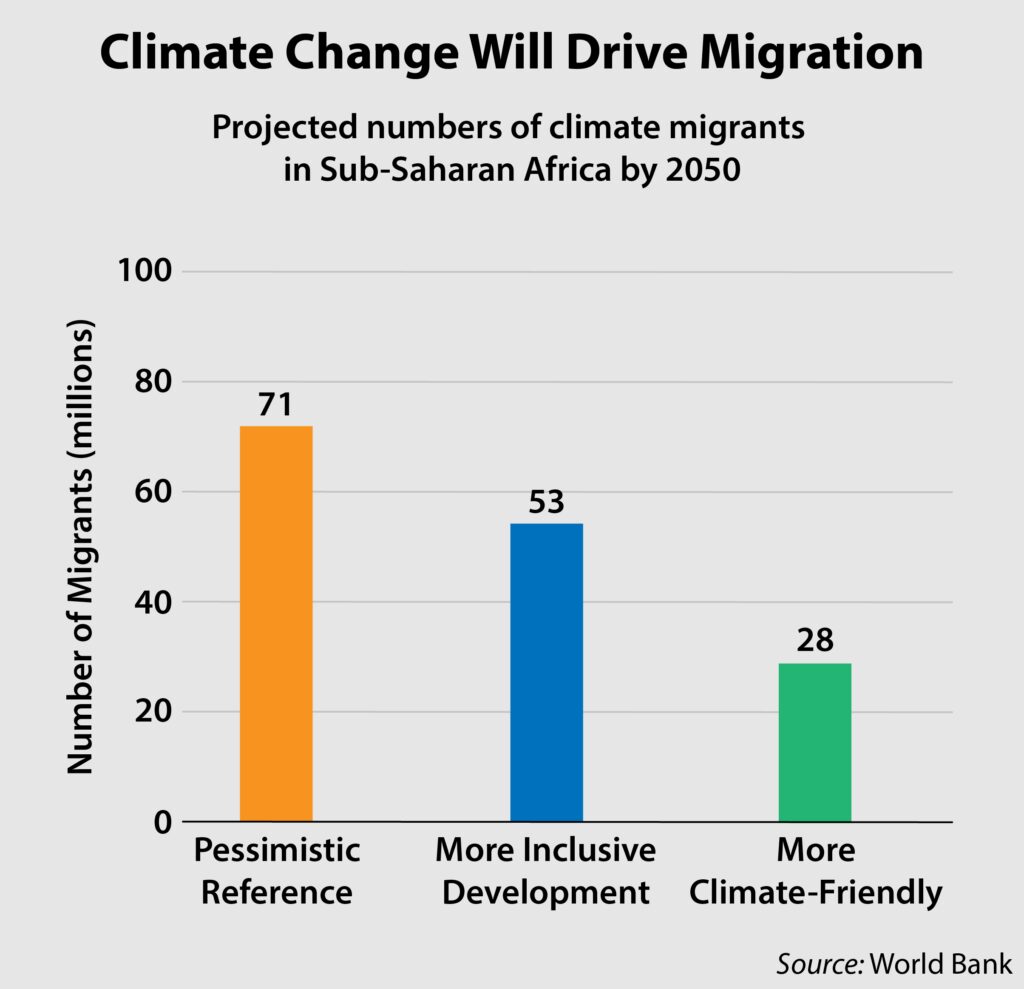

Climate Change Will Create More Environmental Migrants

The steady rise in global temperature due to climate change is making certain regions in Africa uninhabitable (due to water scarcity, intolerable heatwaves, and increased disease outbreaks, among other factors), causing a rise in migration.

Climate change is accelerating the pattern of rural to urban migration into Africa’s metropolises. Between 2020 and 2030, Africa’s seven largest coastal cities—Lagos, Luanda, Dar es Salaam, Alexandria, Abidjan, Cape Town, and Casablanca—are projected to grow by 40 percent. The dual strain of population growth and rising seas on infrastructure, agriculture, and access to water for African citizens in coastal cities will heighten the risk of governance and security crises.

Natural Disasters—from longer droughts to stronger storms and floods—are also contributing to a rise in migration. Over the last decade an average of 2.5 million Africans have been temporarily displaced each year due to natural disasters. The repeated damage to infrastructure and livelihoods impacts resilience, causing more to relocate longer term, even permanently.

Some African Migrants Continue to Face Acute Risks

An estimated 15 percent of African migrants, mostly those travelling without official documentation, face high levels of vulnerability to exploitation and trafficking, either along their route or in their destination country.

Libya, for example, remains a very dangerous country for migrants, with ongoing reports of murder, torture, rape, persecution, and enslavement of migrants by traffickers, militias, and even some state authorities.

North Africans still lead the number of Africans crossing the Mediterranean to Europe. The continued backsliding of democratic institutions and economic hardship in North African countries like Tunisia, Egypt, Algeria, and Libya will likely lead more people to look toward Europe.

Africa has documented more than 9,000 migration-related deaths since 2014. More than 25,000 have also disappeared crossing the waters between Africa and Europe.

Many countries continue to treat migration as a crime rather than a symptom, namely of limited economic opportunities and difficulty accessing safe, regular pathways for migrants.