When United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres addressed the Security Council in October, he urged it to act against the “epidemic of coup d’etats” plaguing the international community. Guterres’ warning came in the aftermath of a successful coup in Sudan—the fifth in the world that year. Though it’s just started, 2022 has brought even more coup attempts, including a successful one in Burkina Faso on Jan. 23 and a failed one in Guinea-Bissau in early February.

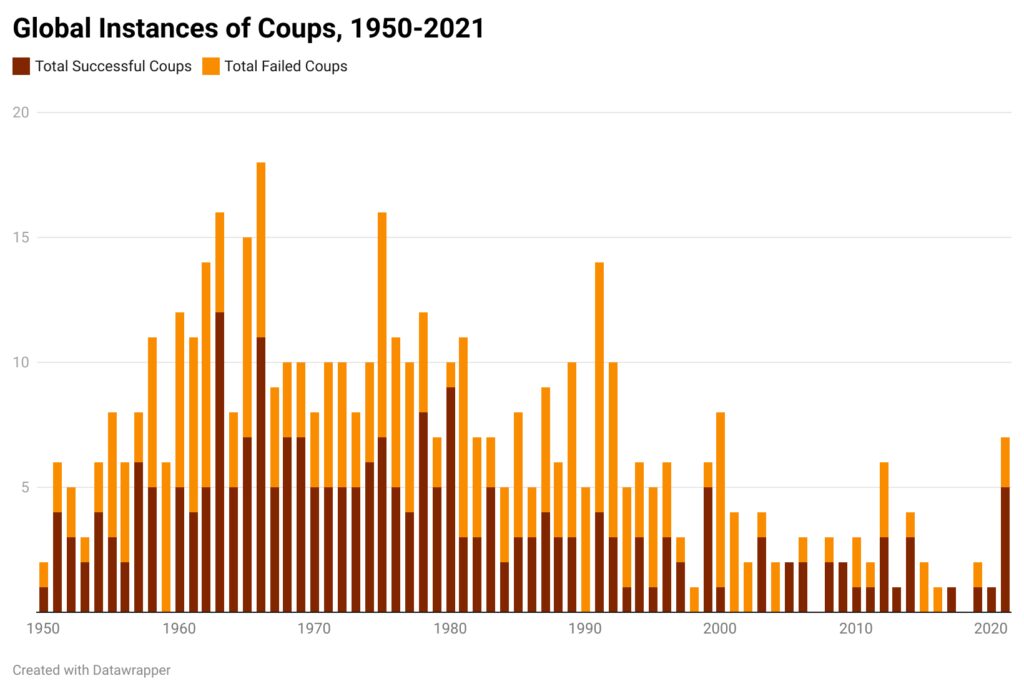

In total, there have been nine military coup attempts since January 2021, of which six—in Myanmar, Sudan, Chad, Guinea, Mali and Burkina Faso—were successful. This recent spree has led some to suggest that, despite waning in the post-Cold War era, “coups are back.” And there is truth to this: Globally, coup attempts, both successful and failed, are at the highest levels seen since 2000.

But other claims about this uptick are less convincing, including Guterres’ reference to the concept of “coup contagion”—that coups, like the common cold, spread. Proponents of this idea point to the fact that several of the recent coups and coup attempts have occurred in the Sahel region of Africa. But this geographic clustering alone is not clear evidence of contagion.

It’s worth taking a moment, then, to assess the truth of this and other common assumptions about coups, and to take stock of what we do know about why they happen—lest we apply the right policy solution to the wrong problem.

Coup Contagion

Coup contagion suggests that would-be coup-plotters in one country learn both that they can succeed as well as how to succeed by watching coup attempts in neighboring states. Although social movements do seem to spread through contagion mechanisms, recent empirical investigations undercut the notion that coups do—and indeed, there is little indication that the recent wave of attempts in the Sahel is a result of information dissemination across borders.

And there are several other reasons to remain cautious about applying the contagion argument to today’s trend. First, these coup attempts were not happening in countries with strong norms against military involvement in politics, so coup-makers were unlikely to be looking to events in other countries for inspiration to intervene. To the contrary, in many of the countries involved in the recent trend, domestic politics are defined by the constant intrusion of the military in civilian politics. Even in Myanmar, which hadn’t had a coup in decades, there was no strong norm against military intervention, because the country had been ruled by military juntas for most of its history.

There is little indication that the recent wave of attempts in the Sahel is a result of information dissemination across borders.Second, most of the affected countries are ones where military actors understand well how coups occur and have no need to learn from events in another country. In fact, these states are in the top 20 percent of countries ranked by the number of coup attempts they’ve experienced since 1950. More telling, nearly all these countries have had recent prior coup attempts; all but Chad and Myanmar had experienced at least one other coup attempt in the previous decade. Sudan, which is one of the most coup-prone countries in the world, has experienced three coup attempts since 2019.

Although coups may not diffuse from one country to the next, there is evidence to suggest that that coups beget coups within a given country, a concept known as the “coup trap.” Mali’s recent experience, with successful coups in 2012, 2020 and 2021, highlights this dynamic. Burkina Faso, where a recent coup followed a failed attempt in 2015 and which historically has been plagued by coups, may be falling into this trap—bad news for its fledgling democracy.

So it is not the case that countries with a low propensity to engage in coups are suddenly having coup attempts. Far more relevant is the fact that many of them—particularly in the Sahel—had been grappling with conditions that are known to spark coups at a time when the international system has become all the more ambivalent in holding plotters accountable. Contagion, it seems, is largely in the eye of the beholder.

Understanding the Causes of Coups

While recent coverage may suggest otherwise, it is important to recognize that coups are inherently rare. During the Cold War, when coup attempts were at their height, there were an average of 9.1 each year. But that number was cut by nearly 60 percent in the decade after the Cold War ended, dropping to less than four coups per year. Since 2000, the total number of coup attempts has fallen even farther, to around 2.6 per year.

The uncommon nature of coups makes predicting when and where they will occur a difficult task. Still, we do know that coups are more likely to happen in countries with high levels of previous coups, low levels of economic development and anocratic regime types—that is, governments that are neither democratic nor authoritarian, but that share some characteristics of both.

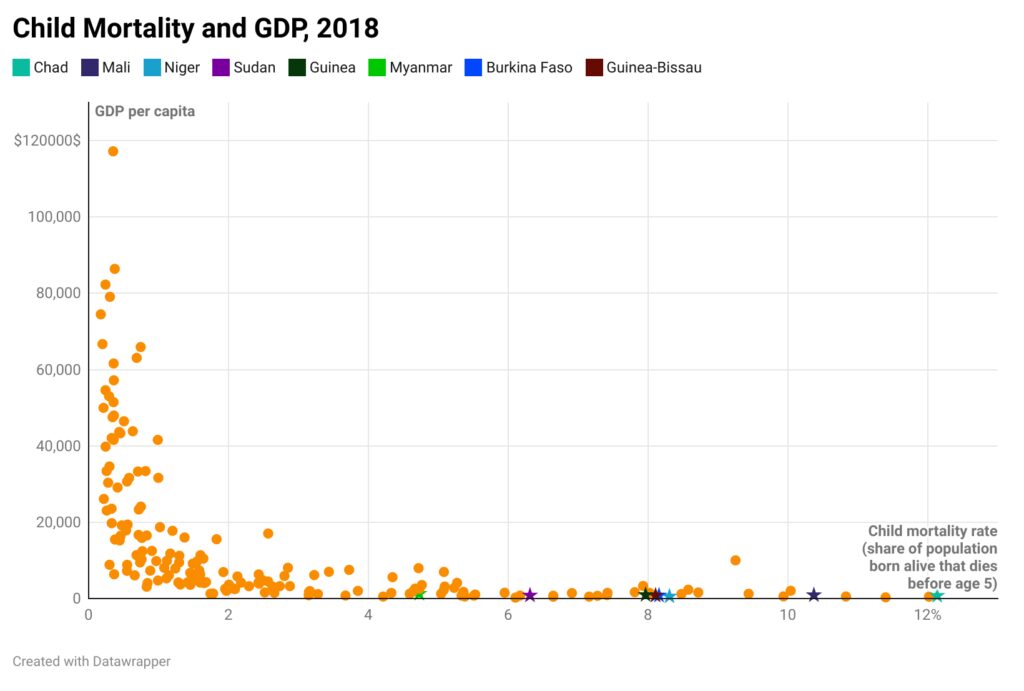

The poorest states in the international system have historically been the most prone to military takeovers. All seven of the states that have experienced a coup attempt since January 2021 were in the bottom 20 percent of countries ranked by GDP per capita, according to World Bank data. Each also sat in the bottom quarter for other development measures, like infant mortality.

Of course, there are many poor countries that do not experience coups, so economic conditions are only one piece of a larger puzzle. Another important one is regime type. Democracies, especially consolidated ones like the U.S. and the countries of Western Europe, are the least likely to experience coup attempts. Autocracies that engage in serious repression, like Saudi Arabia, are also less likely to experience them.

It is anocracies that are the most at risk for coup activity. These governments, many of which acquire or keep power through fraudulent or irregular elections, tend to lack legitimacy in the eyes of the public, and their relative restraint in terms of repression offers fewer deterrents to insurrectionists. Most states with recent coup attempts can be categorized either as hybrid regimes or as fledgling democracies that lack consolidated institutions and norms.

These structural factors—economic development and regime type—can explain which countries are likely to experience a coup attempt. But in order to understand when a coup might occur, we need to look at triggering events.

One proximate cause of coups is conflict, which, it’s worth noting, has been on the rise in the Sahel. Upticks in insurgent activity by the al-Qaida affiliate Jama’at Nasrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin and the Islamic State’s West Africa Province have pushed the security sector in several West and Central African countries to the brink, exposing deficiencies and exacerbating internal tensions to a breaking point.

Some observers argue that conflict has a direct impact on coup activity. For example, in Burkina Faso, armed clashes with insurgents had risen some 200 percent between November 2018 and March 2019, leading fatalities to shoot up 7,028 percent in the same period. Many see this year’s coup as a direct consequence of the country’s fragile security environment and insufficient government responses. Our research suggests that these are just the right ingredients for coup activity, particularly in young democracies with under-resourced militaries.

Others argue that conflict does not independently cause coups, but rather compounds existing governance issues in weak states that exacerbate the grievances of potential coup-plotters. For example, the World Food Program estimates that nearly 8 million people in Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso lack consistent access to food, making this region one of the most food insecure in the world. Conflict in the Sahel has only exacerbated this problem and related governance problems, with current estimates suggesting there are 2.1 million internally displaced people between the three countries. The inability of the state to efficiently provide public goods—including food and security—generates exactly the type of grievances that can galvanize coup-plotting.

Elections and protests are also important triggering events. Elections and electoral outcomes, especially those marked by irregularities or suspected fraud, can tip the scales toward coup activity. Guinea’s 2021 coup came just under a year after its president, Alpha Conde, used a disputed national referendum to change the constitution, allowing him to run in the October 2020 election and secure a previously prohibited third term.

An important part of this equation is that elections, like increasing security threats, can spark protests—and in turn, protests can spark coups. As we explained in a 2016 paper, protests send important signals to coup-plotters about a domestic audience’s likely reaction to a putsch. Anti-regime protests calling for President Roch Marc Kabore’s resignation dominated the Burkinabe scene in the lead up to the 2022 coup that ousted him. Mali’s August 2020 coup followed three months of protests demanding President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita’s departure. Likewise, Sudan’s 2019 coup, which ousted dictator Omar al-Bashir after 30 years of rule, came after months of protests initially sparked by rising food and fuel prices. A dissatisfied public can provide either motivation or justification for an intervention.

Eroding International Norms

While domestic factors are critical for determining how vulnerable a particular state is to coup attempts, another contributing factor at work today is the erosion of the post-Cold War international norm against coups. During the course of the Cold War, the United Nations Security Council did not once criticize a coup, and in fact, the international community did not seem to perceive governments that emerged from coups as illegitimate. This changed later on, as international organizations like the U.N. and World Bank, regional groups like the Organization of American States and African Union, and donor states like the U.S. all began to impose diplomatic and economic penalties after successful coups. That less hospitable climate has been credited with substantially decreasing the number of coup attempts since the 1990s, largely by deterring would-be coup-makers.

However, recently the norm against coups has begun to fade away. States and multilateral groups have been increasingly inconsistent about punishing coup-makers with sanctions, diplomatic isolation and other negative consequences, in part because of changes in the structure of the international system. The rise of China, resurgence of Russia and increased activity of nondemocratic regional powers has created a more permissive international environment.

Much like the Cold War era, states can now find patrons regardless of their adherence to democratic norms.International institutions have also faltered. Recently, the U.N. Security Council has been hesitant to label power grabs as “coups,” let alone to condemn coup-plotters. Following Myanmar’s coup, for instance, the Security Council failed to condemn the military’s actions, and it stopped short of doing so again after Burkina Faso’s recent coup. In the latter case, the council even refused to refer to the transition of power as a coup.

Why would the U.N. Security Council fail to condemn coups strongly when there is evidence that international responses to coups can make a difference? For one thing, politics matter. Critical, veto-wielding players like Russia and China have proven unwilling to condemn the recent coup attempts. China has signaled support for the junta in Myanmar, increasing foreign direct investment and potentially blunting the force of the targeted sanctions imposed by the U.S. and other actors. For its part, the United States has been silent about the coup in Chad, which is an important counterterrorism partner for Washington.

Much like the Cold War era, states can now find patrons regardless of their adherence to democratic norms. For example, Sudan can rely on the support of Gulf states, regardless of what condemnation or cuts to foreign aid the U.S. directs at the new junta. This ability of coup-imposed governments to pivot and find support from undemocratic major powers is an important dimension shaping future coup activity. We know, after all, that coup-plotters try to anticipate the challenges they might face after a successful coup when they make initial calculations on whether or not to attempt one. They may not take inspiration or tactics from neighboring states, but they do try to anticipate the challenges they might face after a successful coup.

Regional organizations have remained somewhat more resolute in their opposition to coups, but they also have a more limited ability to effect change. The African Union has condemned the recent coups and suspended the states involved, but the consequences of these actions are slight, meaning they may not be enough to deter future coup attempts elsewhere. The Economic Community of West African States, or ECOWAS, has gone further by imposing sanctions on Mali—but these were not very effective, not least because neighboring Guinea has refused to participate and because Malian citizens themselves have objected. As a result, ECOWAS decided against imposing sanctions against the coup leaders in Burkina Faso. It did send troops to Guinea-Bissau to protect that government from future coup attempts, but it is easier and less controversial to support an incumbent than to push one out.

What Comes Next

While there are good reasons to be concerned about the implications of the recent coups and coup attempts, it is too early to say whether there will be many more, and too difficult to say how best to address the attempts that do follow.

It is important to remember that coups remain both relatively rare and highly varied. The coup in Burkina Faso emerged from a mutiny. The one in Guinea emerged from a controversial third presidential term. And the coups in Myanmar, Chad, Mali and Sudan emerged, broadly speaking, from contested democratic transitions. Compounding the challenge of both diagnosis and treatment is the fact that contingency and chance play a critical role in the dynamics and timing of coup attempts. Coup-makers face heavy potential costs if they fail, so they are highly attuned to local, intra-military dynamics—which is the hardest factor for outsiders to change.

The anti-coup norm successfully deterred coups for three decades, but this norm took considerable effort and time to build and maintain, and much less time to degrade. Western democratic nations no longer prioritize democracy to the same extent as before, and authoritarian countries can increasingly offer significant diplomatic and financial support to those that the West is willing to sanction.

But for all the unpredictability, there are at least two takeaways worth keeping in mind in the months and years ahead. The first is that Western countries must place a higher value on democracy, both at home and abroad, if they wish to live in an international community of free, democratic states. Norms require consistent effort in order to generate the almost gravitational effect that makes them so powerful—and that is especially true in circumstances like today’s, when they become costly to enforce.

Second, Western actors should avoid policies that act on states without working with partners in government and civil society, especially in African countries with factors that might make them more vulnerable to coups. Democracy, development and peace cannot be generated from the outside alone. Any effective policy to discourage coups will have to involve working with and empowering actors within coup-prone states.