The term Maghreb (Arabic for “the Sunset”) refers to the countries of the Sunset – the North African West – as opposed to Mashreq (“the Levant”), which refers to the countries of the Rising Sun – the Arab East. In its traditional sense, the Maghreb includes Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia, three ancient Amazigh/Berber countries, Islamized and Arabized. In 1989, the Arab Maghreb Union (AMU) was created, which includes, in addition to these countries, Libya and Mauritania. (1)

In his book entitled: ‘’The Invention of the Maghreb. Between Africa and the Middle East”, Abdelmajid Hannoum argues quite forcefully that the Maghreb is a French colonial invention: (2)

“Consider the name Maghreb; it is almost unchallenged. It appears Arab, even local, from the heart of the local tradition, yet it is a francophone name as well, invented from a translated Arabic tradition, its ’foreign’ resonance hiding its colonial invention.” (3)

And he goes on to say:

“Hence, the sad observation that French—not Arabic—remains the language of the study of the area, its history, its culture, its population, even its intimate sexuality.” (4)

Reviewing this interesting work, Julien Lacassagne writes in Orient XXI: (5)

“Hannoum exposes the consequences which the colonial narrative had—and continues to have—on the genesis of North-African regional groupings since, in his view, colonial rhetoric was not content to wreak havoc among existing identities and traditions but created others out of whole cloth. These seem authentically local but have never been any such thing. The term Maghreb, he claims, is not the least of these inventions. “

What is the Maghreb?

The Maghreb, “the great Maghreb”, is a region located in North Africa, the western part of the Arab world corresponding to the Arab-Amazigh/Berber cultural space, included between the Mediterranean Sea, the Sahelian strip and Egypt (not included in the limits).

The first Muslim conquerors called western North Africa, Jazirat al-Maghrib, i.e. “Island of the Sunset”, the countries isolated from the rest of the Arab world west of the Gulf of Sirte. During French colonization, the term Maghreb in the strict sense referred to French North Africa, which included Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia.

Amazigh/Berber activists use the neologism of Tamazgha, challenging the name “Maghreb” on the grounds that it is not the original name of the region but a term used in Arab-Muslim historiography. However, this term denotes a certain variety of appreciation according to the tendencies of these activists, which sometimes goes beyond the geographical framework; neither do they call it Barbary, (6) a term that comes from its designation, at the time of the Renaissance, by the British, Italians, the French and the Spaniards. Through the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, English sources often referred to the region as the Barbary Coast (7) or the Barbary States, a term derived from the demonym of the Amazigh/Berbers.

The notion of “Greater Maghreb” emerged in the 1950s and refers to an area that also includes Libya and Mauritania, as well as the disputed territory of Western Sahara. It refers to a geographic space, but this concept remains little used. The territory of Azawad (northern Mali) and western Niger are culturally close to the rest of the Maghreb. The eastern boundary is more blurred: Cyrenaica, in Libya, remains strongly influenced by the Mashreq, while Siwa, (8) Qara and some cities in western Egypt are Amazigh/Berber-speaking oases in Egyptian territory. The Canary Islands, west of Morocco, are part of the Amazigh/Berber historical-cultural area but have never been Arabized or Islamized, and for this reason are not part of the Maghreb.

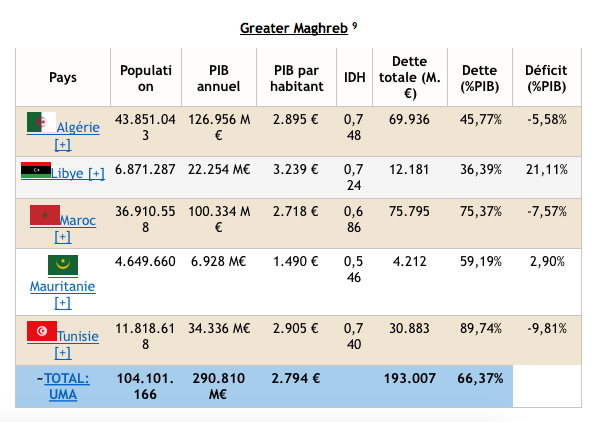

The Maghreb occupies an area of about 6 million km2 shared between the Mediterranean basin and the Sahara Desert, which covers most of its territory: the population, about 104 million inhabitants, is therefore very unevenly distributed, and concentrated mainly on the coastal plains.

The Maghreb, located at the crossroads of the Arab world and the Mediterranean and African civilizations, has been a geographical unit for more than a thousand years, characterized culturally by the fusion of Arab-Amazigh/Berber elements. Its inhabitants, known as Maghrebis, have been living in the Maghreb for more than a century. Its inhabitants, known as Maghrebis, are mainly descended from Amazigh/Berbers, (10) most of whom were Arabized between the eighth century and the present. Although distant from each other in many respects, the Maghreb and Mashreq are nevertheless linked by the Arabic language and Islamic culture. The contemporary history of the Maghreb is marked by the French, Spanish and Italian colonizations, but also by its proximity to Western Europe. Since 1989, an attempt at political and economic rapprochement has been initiated with the creation of the Arab Maghreb Union.

Geography

In its Saharan part (80% of the territory), the Maghreb is an arid zone. Its desert climate is more accentuated in the east (Libyan desert), rainfall is rare and irregular (less than 100 mm annually). Tanezrouft (Algeria) and Fezzan (Libya) hold the record for minimum rainfall (less than 20 mm). In summer, daytime temperatures are very high (up to 66°C in In-Salah, Algeria), but winter nights can be extremely cold.

From the continental zones to the Mediterranean border, the climate becomes increasingly temperate. Thus, the northern part of the Tunisian Dorsal (more than 400 mm) receives more rain than the south (300 mm). The coastal areas are rainy from September to May (300 to 500 mm in Mount Cyrenaica; 400 mm in Algeria). The rest of the year, the weather is hot and dry (22 to 29 °C in Algiers), influenced by winds blowing from the Sahara (sirocco, cheheli or chergui). Morocco is the rainiest of the Maghreb countries (810 mm in Tangier).

From Tobruk to Agadir, the Maghreb has a green coastline, which extends for nearly 5,000 km along the Mediterranean Sea, up to Tangier, and for 700 km along the Atlantic, from Tangier to Agadir. The coast then becomes desert until the mouth of Senegal, 1 500 km south.

The Maghreb space is dominated in the northwest by the Atlas mountain system, which forms a barrier between the Mediterranean coast and the Sahara. South of the Atlas, the desert occupies nearly 80% of the territory. In the transition zone, between mountains and desert, and on the coastal strip that separates the mountains from the sea, is concentrated most of the arable land. (11)

The vast mountain system of the Atlas extends over 2,400 km from the mouth of the Oued Sous, in southwestern Morocco, to Cape Bon and the Gulf of Gabes, in northeastern Tunisia. (12)

In Morocco, the High Atlas, the most important chain, culminates at Jebel Toubkal (4,165 m). It is separated from the Middle Atlas in the northeast by the Moulouya wadi – which flows into the Mediterranean not far from the Algerian border -, and the Anti-Atlas in the southwest by the Sous wadi, which flows towards the Atlantic, south of Agadir.

The Tellian Atlas extends according to some from Tangier to Bizerte, including the Rif mountains, which peak at 2 452 m altitude at Jebel Tidighine in northern Morocco, to the Kroumirie in eastern Tunisia. Others limit it to the Algerian coast. South of the Tell, the Saharan Atlas rises between the Algerian highlands and the Sahara. It extends to the east by the Aures and the Tunisian Dorsal (Jebel Chambi, 1 544 m).

Many wadis descend from these mountains. Some flow towards the Mediterranean, others towards the Sahara. They drain the narrow and fertile plains of the coastal valleys (Tunisian Medjerda, Algerian Cheif) as well as the semi-arid highlands of the interior.

In Libya, the fertile area on the Mediterranean border is very small. It includes Tripolitania to the northwest, a narrow coastal strip topped by hills (Jebel Nefousa), and Cyrenaica to the northeast, a series of deeply indented plains and hills (Jebel Akhdar). Tripolitania and Cyrenaica are separated by the immense Gulf of Greater Sirte, bordered to the south by the Sirte Desert, part of the Sahara that extends to the Atlantic coast.

The Sahara covers the entire Western Sahara, most of Mauritania, Algeria, and Libya, as well as many areas of Morocco and Tunisia. It continues east to Egypt and Sudan, and south to the semi-arid areas of the Sahel (Chad, Niger, Mali, Senegal).

The largest desert in the world is made of an eroded sedimentary base. Its relief includes basins (Tafilalet, in Morocco) interspersed with plateaus (Ennedi, Tademaït and Tassili) and a few isolated volcanic mountain systems whose highest peaks do not exceed 3,000 m (the Hoggar, in southern Algeria, and the Tibesti, on either side of the border with Libya and Chad). (13)

The differences in temperature and the sandy winds have shaped the Saharan landscape, where the regs dominate, flat spaces covered with stones and gravel (Tanezrouft, in Algeria, and Grand Reg Libya), hostile and bare. The ergs (sand dunes) cover only a quarter of the Saharan territory (Western Erg and Eastern Erg, in Algeria; Idehan de Mourzouk, in Libya).

Geographical similarities

The geographical limits of the Maghreb are difficult to define. A distinction is made between a central Maghreb composed of Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia, which covers an area of 3 million square kilometers, or more than five times the size of France, and a large Maghreb that covers, with Mauritania and Libya in addition, an area of approximately 5.7 million square kilometers. The term Maghreb – and not North Africa, which includes Egypt but excludes Mauritania – generally refers to the central Maghreb, which forms a relatively homogeneous whole; but it also sometimes refers to the greater Maghreb, which has been an institutional reality since the creation of the Arab Maghreb Union (AMU) in 1989. This Maghreb group, concentrated on the northwestern part of the African continent, is marked by its proximity to Europe and its membership in the Mediterranean civilization.

The historical and cultural foundations on which the geopolitical grouping is based, which extends from the Mediterranean to the Sahara, at the crossroads of Europe and Africa, are all assets for the creation of a Greater Maghreb.

Despite their own characteristics, the Maghreb countries have great geographical similarities. Occupying the north-western part of the African continent and covering some 5,7 million km2, they share the same topographical contrasts: a narrow coastal plain, large mountainous areas (the Tell mountain range in Algeria and the Atlas mountain range in Morocco) and an immense desert area covering five-sixths of the surface.

The relief and climates are also contrasted. Aridity increases from the coast to the desert margins, and rainfall is abundant only in the mountainous areas. Finally, inter-annual variations strongly influence the climate: periods of drought can last several years. The societies of the Maghreb have adapted well to the natural constraints of the different environments, establishing exchanges between complementary regions.

Traditionally, these societies turned their backs to the sea and looked inland: the Sahara and the gold routes. In ancient times, Phoenician and Roman settlers, and then, in modern times, French settlers, settled on the coast and developed the coastal plains. For a long time, these countries had in common the opposition between densely populated mountains – given the ratio of cultivable land to population – and sparsely occupied plains. The development of mountain environments by agro-pastoral populations has been important, while the plains have long remained the domain of nomadic herders. It is only very recently, since the French colonization, that they have experienced agricultural development.

Originally, it was the famous historian, sociologist and geographer Ibn Khaldun (1332-1406), who used the expression “Jazirat al-Maghrib“, (“the island of the Sunset”), to designate the region surrounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Sahara Desert to the south.

Amazigh common denominator

The five countries of the Greater Maghreb have in common an ancient Amazigh/Berber population that ensures a profound originality within the Arab world. It is astonishing to note the maintenance of the Amazigh/Berber culture and language after some thirteen centuries of the penetration of the Arabic language. Today, there are 33% Berber speakers in Morocco, 21.5% in Algeria, 20% in Mauritania, 5.4% in Libya and 3% in Tunisia, i.e. approximately 14 million Amazigh/Berber speakers for 48 million Arabic speakers. (14)

If the ancient colonizations have left few traces, the Arab conquest and the Islamization that accompanied it, from the second half of the seventh century, were decisive. Although the Amazigh/Berbers put up strong resistance to this conquest, (15) they converted massively to the new religion: thus, the troops who crossed the Straits of Gibraltar a few decades later were essentially composed of Islamized Amazigh/Berbers, and the Amazigh/Berber revolts against the Arabs were carried out in the name of a protesting Islam (Kharidjite and Mozabite movements). Trans-Saharan trade, which played a predominant role at the time, brought Islam to Mauritania. (16)

Moreover, two Berber dynasties achieved the first unification of the Maghreb: the Almoravids (1061-1147) and the Almohads (1147-1269). The first, nomads of the Sanhadja tribe, came from the Sahara and conquered as far as the kingdom of Ghana after seizing Aoudaghost, a large caravan center located in present-day Mauritania. They then conquered the whole of Morocco after founding Marrakech (1062), and extended their empire north to Andalusia and east to Tlemcen (Algeria). Their power was later challenged by the Almohads, who came from Tinmel in the High Atlas and were also great religious reformers. After calling for a holy war against the Almoravids (1147), the Almohads unified under their command all of North Africa, from Morocco to Ifriqiya, with the conquest of Tunis and then Tripolitania. (17) This union was ephemeral, but it occupies an important place in the Maghrebi imagination; it prefigures the dream of the Greater Maghreb, whose treaty of Arab Maghreb Union (AMU) is trying since 1989 to lay the foundations.

Rarely in history has the Maghreb been unified: that of the Fatimids of the 10th century and the Amazigh/Berber dynasty of the Almohads of the 12th century are now an imaginary sunset… And even though, centuries later, the Maghreb seems to be uniting for independence, it is essentially the pressure of the yoke of the colonial powers that serves as a unifying element. Roger le Tourneau already relativized at the time the relevance of the idea of North African unity, which, before being a constructive idea (…) was mainly manifested as a defense reflex … (18)

Thirty-one years after the 1958 Tangier conference, the first expression of a dream of Maghrebi unity very quickly aborted, Nouakchott, Rabat, Algiers, Tunis and Tripoli signed the Marrakech Agreement. The first articles refer to “brotherhood”, “progress”, “peace”, and “free movement” and define three main axes to be developed: a political, economic and cultural component. But the chimerical Arab unity has quickly given way to the logic of national interest. Moreover, why an “Arab” union? Would the cultural diversity of the Maghreb contain the seeds of division? Is it not rather in it that lies the wealth of this region? The inexhaustible question of the Western Sahara has also very quickly emerged as an obstacle to Maghrebi unity. (19)

The Moroccan-Algerian dispute appears to some observers as a pretext for “regional leadership”. Thus, the Maghreb states have only themselves to blame: in some respects, Tunisia and Morocco seem more interested in deepening their ties with the EU. However, their largest economic partner is careful not to encourage them to unite: indeed, the absence of the EU in the Maghreb project is notable.

If only for economic reasons, the Union appears to be a question of survival. A large part of world trade now takes place in regional integration areas. Thus, the trade relations of the European Union, ASEAN and Mercosur are respectively 60%, 22% and 19% regional; those of AMU reach only 3%… The stakes are high for Maghrebi economies and societies whose disunity makes them a little more vulnerable and marginal within the global economy every day. Not to mention that the process of European integration in the East has significantly affected economic relations between the two shores.

The more the Maghreb is disunited, the weaker its bargaining power with the European Union. The Union would give it more credibility and allow it to assert its own interests. To the asymmetrical links between the Maghreb and Europe, the Maghrebis must respond with integration and South-South cooperation, a fundamental issue for development. But there is no question of the Maghreb uniting in order to better oppose Europe: is not the Maghreb union in itself a prerequisite for any Euro-Mediterranean project such as the Union for the Mediterranean? And this union must not only be achieved from the perspective of Europe alone, the Maghreb must take up its own challenge. Taken separately, the Maghreb’s domestic markets are fragmented, even though they represent a potential market of 75 million consumers… One remembers the craze of foreign investors towards the countries of Central and Eastern Europe on the eve of joining the European Union. All of a sudden, these countries presented new perspectives and potentialities.

If one relies on the European experience, one can see the Arab Maghreb Union in an optimistic light: who would have thought, at the end of the Second World War, that cooperation, and then economic integration, would take precedence over historical political tensions?

Understanding Moroccan-Algerian rivalries

Algeria and Morocco, neighboring countries sharing common languages, culture and history, have had conflicting relations for over half a century.

Since its independence in 1956, Morocco has claimed the border regions of Tindouf and Bechar as part of the “Greater Morocco” project. This project, led by the Istiqlal party, aimed to restore the kingdom’s sovereignty over the regions it controlled before colonization. In 1961, King Mohammed V of Morocco reached an agreement with GPRA President Ferhat Abbas to renegotiate the border line after Algeria’s independence. Nevertheless, this agreement was not followed up after Ben Bella took power and Ferhat Abbas moved away in 1962.

Following the refusal of the Algerian leaders to respect the agreement signed by the GPRA in 1961, relations with Morocco escalated and led, in September 1963, to the outbreak of the Sand War. (20) This conflict, which pitted the armies of both countries against each other, ended with the signing of a definitive cease-fire on February 20, 1964. The borders remained unchanged and this event reinforced the feeling of mistrust between Algeria and Morocco.

A few years after the end of the Sand War, Algerian and Moroccan troops clashed again in the first battle of Amgala. This battle took place from 27 to 29 January 1976 in the oasis of Amgala, in Western Sahara, a territory occupied by Morocco since 1975. The Western Sahara issue is one of the main reasons for the rivalry between the two countries. Algeria supports the Polisario Front, a political and military organization claiming independence for this disputed territory, which Morocco considers a terrorist organization. Morocco has proposed I April 2006 an autonomy plan for the Western Sahara. (21)

In 2009 US Secretary of State Hilary Clinton said the following in regards to Morocco’s plan for Sahrawi autonomy: (22)

“Well, this is a plan, as you know, that originated in the Clinton Administration. It was reaffirmed in the Bush Administration and it remains the policy of the United States in the Obama Administration. Now, we are supporting the United Nations process because we think that if there can be a peaceful resolution to the difficulties that exist with your neighbors, both to the east and to the south and the west that is in everyone’s interest. But because of our long relationship, we are very aware of how challenging the circumstances are. And I don’t want anyone in the region or elsewhere to have any doubt about our policy, which remains the same.”

The Sherifian kingdom also considers its eastern neighbor as a stakeholder in this conflict and requires its presence as a prerequisite for any negotiation to settle this issue permanently. A requirement to which Algeria has always refused to respond favorably, because it considers the Western Sahara issue as a conflict involving exclusively Morocco and Western Sahara.

In addition to border concerns and the Western Sahara file, another event has contributed to tarnish relations between the two countries. In 1994, Morocco was hit by a terrorist attack in a hotel in the tourist city of Marrakech. The Moroccan authorities, accusing the secret services of their neighbor of being involved in this attack, decided to send back all Algerian nationals without a residence permit from the territory of the kingdom.

Algeria retaliated by closing the land border and both countries imposed entry visas on each other. The land border between the two countries is still closed, despite the lifting of visas in 2004 by Morocco, then in 2005 by Algeria.

Today, there are still periods of crisis in relations between the two countries. One of the most recent events was a crisis caused by statements made by the Moroccan consul in Oran. The diplomat referred to Algeria as an “enemy country” during a meeting with Moroccan nationals. These statements provoked a heated diplomatic crisis that resulted in the departure of the Moroccan consul. More recently, President Abdelmadjid Tebboune returned to the subject in an interview with the France 24 channel. (23)

“Algeria has no problem with the Moroccans, but it seems that it is the Moroccan brothers who have a problem with us,” he said. So have Algeria and Morocco begun to take the path of appeasement? Or is this just a temporary lull in the conflict that has pitted them against each other for over half a century?

Rivalries in Africa

Morocco and Algeria have been fighting a merciless battle for decades to extend their influence, with the Sahara issue as a backdrop.

The spat between Morocco and Algeria seems to have intensified in 2016 since Morocco’s request to return to the African Union (AU) and its diplomatic offensives in sub-Saharan Africa. So many initiatives that Algeria hopes to thwart.

Long-time diplomatic adversaries, Morocco and Algeria have also engaged in a semantic battle. On July 17, Morocco officially requested “its return” to the institutional family that is the African Union (AU). In his letter to the chairman of the African Union, Mohammed VI wrote: “For a long time our friends have been asking us to return to them, so that Morocco can regain its natural place within its institutional family. This moment has arrived. “

Three days after the announcement, reacting to Morocco’s wish to join the Pan-African organization, Abdelkader Messahel, Algerian Minister of Maghrebi Affairs, the African Union and the Arab League, merely recalled that Rabat’s move should be considered as “an accession” and not a “return” to the AU. He explained that Morocco withdrew from the Organization of African Unity (OAU) in 1984, and that the latter was dissolved in 2002 and replaced by the African Union (AU).

On December 2, 2016, King Mohammed VI concluded his African tour with a visit to Nigeria. In parallel to the royal visit to this country, a Moroccan-Nigerian business forum had opened in Lagos in the presence of representatives of Moroccan and Nigerian employers, as well as major groups and officials from both countries.

Thousands of kilometers away, Algiers organized the first ever investment and business forum where more than a thousand businessmen, ministers, banks and companies from across the continent were expected. The Algiers Forum had the ambition to boost economic cooperation within the continent.

If the king has concluded dozens of agreements in the countries where he passed, the organization of the Algerian Forum has, however, not been a success. The Algerian news site TSA-Algeria titled “African Investment and Business Forum of Algiers: chronicle of an incredible scenario”, the day after the fiasco.

The royal visit to Nigeria, one of the world’s largest gas producers, ended on 3 December 2016 with the conclusion of a partnership between the two countries to finance a gas pipeline project. The pipeline would carry Nigerian gas along the entire West African coast to Morocco. (24)

On December 13, 2016 while Mohammed VI was back in Morocco where he chaired a first working meeting at the Royal Palace in Casablanca on the “technical feasibility and financing of the project” of Nigeria-Morocco gas pipeline, Algiers hosted the vice-president of Nigeria, Yemi Osinbajo.

At the end of a visit during which he met with President Abdelaziz Bouteflika, his Prime Minister Abdelmalek Sellal, and the head of Algerian diplomacy Ramtane Lamamra, the Nigerian vice president recalled in a statement reported by the official Algerian agency APS the joint projects between the two countries, in this case the trans-Saharan road Algiers-Lagos, the trans-Saharan gas pipeline, linking Nigeria to Europe via Algeria, and the fiber optic link Algiers-Abuja.

Algeria had in fact been negotiating its gas pipeline project with the Nigerian government since 2002, but this project remained on hold for reasons of financing and security. It was enough for Morocco to announce a similar project for Algiers to decide to relaunch the project.

While Algeria has so far mainly counter-attacked to block Moroccan projects, Morocco has taken the lead on the migrant issue. If the rumor of a new wave of regularizations had been in the air for several weeks, it was confirmed by a royal decision on December 12, 2016 as neighboring Algeria carried out a wave of arrests of sub-Saharan migrants on its soil. More than 260 Malians deported from Algeria in this large-scale operation have accused Algerian security forces of violence, according to AFP.

Better still, Morocco has been generous to these migrants expelled from Algeria. On December 15, 2016 King Mohammed VI gave instructions for “emergency aid” from the Mohammed V Foundation for Solidarity, the Moroccan Agency for International Cooperation (AMCI), and the Ministry of the Interior to be granted to these expelled people who are in an extremely precarious situation in a center in northern Niger. This action consisted in the distribution of a humanitarian kit composed of food products, blankets and tents, for a total volume of 116 tons.

Facing economic challenges separately

In 2011, the Arab Spring broke out. Driven by the growing frustration of citizens faced with leaders who were deaf to their emancipatory aspirations, the “revolutions” spread throughout the region. With disparate political and social consequences. While Tunisia has succeeded in its democratic gamble, Libya has plunged into chaos. But for the past few years, another revolution has been underway. This one is economic. New technologies, environmental issues and concerns about governance have shaken up Maghreb leaders, forcing some to review their development model. And to turn, also, to other partners, less traditional. Where do the various Maghreb countries stand on these issues? Is there also an intra-regional dynamic?

Despite political, social and economic crises, there has been a real economic transformation in these countries, driven by a new generation of managers. Their posture differs from that of older managers. Environmental and digital issues have also contributed to this upheaval.

The economic situation has not changed since 2010. Instability and political uncertainty have weighed on economies. In Morocco, the austerity measures taken in 2013 have spurred a timid recovery. Algeria, which suffered the full force of falling oil prices in 2014, is now in a recession. The government is torn between austerity and managing social risks.

In Tunisia, the debts incurred following the revolution have limited the investments that should have been made in education and health. This is a real problem. The economy was better under Ben Ali, it is true. But the country has done a real job of upgrading governance, which could bear fruit later.

There is a dynamic. Governments have realized that there is a need to focus on SMEs in countries where there are few large companies, apart from the public sector. Morocco and Tunisia, for example, have greatly increased their subsidies to small companies. In Algeria too, but in a slightly different way. The country has set up credit facilities for microenterprises, supported measures for entrepreneurship among the unemployed or for housewives wishing to open a home-based business.

Morocco has focused on the development of new technologies. Techno parks and start-up incubators have really taken off and inspired other countries in sub-Saharan Africa, such as Côte d’Ivoire. The democratization of the Internet and telecoms has also made access to microcredit services more accessible. The question now is how to accelerate the pace.

In Algeria, there is a will to change model. It accelerated after the fall in oil prices in 2014. This was also the purpose of the task force set up afterwards. Unfortunately, the prerequisites for change, such as the establishment of a rule of law and an independent judiciary, were missing. These are essential conditions for domestic and foreign companies. In order for them to establish themselves in the long term, everything that is arbitrary must be reduced.

In Algeria, there is a real problem in this area. Distrust of governments has led to chronic instability, which frightens companies. The entire Maghreb will now have to reindustrialize the region and develop services. But it must not follow the Chinese model of 30 years ago. Morocco has already launched initiatives in this area, with industries in the low-tech and agro-food sectors.

Since the advent of the Hirak, political uncertainty and the various blockages that have resulted have been negative for economic activity. Some companies suffered from the imprisonment of their managers. Hasty, brutal decisions have aggravated the crisis. But the Hirak has also had a positive impact: it has put the focus back on issues of governance and accountability. These are essential conditions for profound change.

What is certain is that the Maghreb states do not trade enough among themselves. The very low volume of trade, at 5%, could be doubled or even tripled. To go further, it would be necessary to set up a common market project. But it is not current. Except between Tunisia and Algeria, there are no measures of free movement. Where there is most reluctance is between Morocco and Algeria, a country that believes it will gain nothing.

Europe remains in pole position, followed by China. But it is difficult to trace this trade, because some of it goes through hubs, like Dubai for example. But it is Chinese products that are exported. While consumers have gained in purchasing power, producers have lost a lot. The end of the multi-fiber agreement in 2007, which limited trade in textiles, led to a massive influx of Chinese textiles. And has ruined the Moroccan and Tunisian industries. Over the past decade, Turkey has also become an important partner. The country has also signed free trade agreements with Tunisia and Morocco. But the balance of trade is in deficit. This is the phenomenon of the backlash.

The Maghreb is united for the worst

Everyone could foresee that Algeria’s relations with its two neighboring states would experience difficulties, once the fighting was over and the solidarity in the face of hardship, which had been affirmed because of the community of origin and destiny of the North Africans, had also taken into account the fraternity within the “ummah” that the Arab-Muslims in particular displayed. (25)

If during the struggle against the French authority the leaders of the three countries have experienced difficult periods, the Algerians reproaching their Tunisian and Moroccan “brothers” for insufficient support and interference in their affairs, it is especially since the ceasefire of March 19, 1962 that rages what Mr. Masmoudi once called the “Maghrebite”, this “disease that consists for such a Maghreb country to call the unity of the Great Maghreb while creating divisions.

The divisions have been all too apparent in 1962. But they take two distinctly different forms. The first is essentially the projection onto the two neighboring countries of the internal conflicts that divide the leadership of the FLN. The second is a legacy of the colonial era, the question of whether the borders drawn by France according to administrative convenience, economic interests, strategic concerns or simply the mood of certain proconsuls, must now be challenged by the three countries concerned.

It goes without saying that it is this second problem which is the most serious and the most considerable, for it concerns not only North Africa, but the entire continent and even the whole of the recently decolonized world. The first should not be neglected, however, because it is the one that first set the tone of relations between Algiers, Tunis and Rabat.

It was inevitable that the two sister capitals would be involved, from near or far, in Algerian political debates. And Tunis even more than Rabat, insofar as, for more than five years, the leaders of the FLN had themselves been involved in Tunisian public life, having forged their alliances and established their friendships with this or that Tunisian group or clan, and having let it be known on which side their tendencies and their projects were leaning. Everyone knew, for example, that Mr. Bourguiba and Abbas hate each other; that the Tunisian leader, on the other hand, has a strong affection for Mr. Belkacem Krim, and that he does not carry in his heart Mr. Ben Bella, in whom he sees perhaps the only Algerian leader likely to claim the role of leader of the Maghreb – to which he, Bourguiba, has obviously not renounced. It should be added that the vice-president of the G.P.R.A, has done everything to further inflame these feelings of the Tunisian head of state by inflicting the cruel slap that was his trip to Cairo, immediately after his release from prison and his brief stay in Rabat.

Europe-Maghreb relations: what future?

For a long time, the Maghreb appeared to be a simple backyard of Europe, a sub-region of a Mediterranean area struggling to find its political cohesion. The revolutions of the winter of 2011 have disturbed and redefined these old relationships.

The partnership between Europe and the Maghreb is fifty years old. From the outset, its ambition was to build an area of peace and shared progress in the Mediterranean. After half a century, has this objective been achieved? The answer is no.

As to what regards these relations, Jean François Drevet argues: (26)

‘’Bien qu’elle soit presque aussi ancienne que la création du Marché commun, la promotion d’une relation préférentielle UE-Maghreb ne va pas de soi. On observe une perception inégale des problèmes maghrébins dans les instances européennes : le Parlement européen (PE) est plus sensible aux questions de principe (les droits de l’homme, la démocratie) que le Conseil (plus porté au réalisme). La Commission agit de manière diversifiée suivant ses politiques, où le Maghreb occupe une place variable. Il faut aussi compter avec la concurrence entre les 28 États membres, qui ont des priorités géographiques divergentes : chacun soutient les pays avec lequel il a les liens les plus intenses. ‘’

[‘’Although it is almost as old as the creation of the Common Market, the promotion of an EU-Maghreb preferential relationship is not self-evident. There is an uneven perception of Maghrebian problems in European bodies: the European Parliament (EP) is more sensitive to issues of principle (human rights, democracy) than the Council (more inclined to realism). The Commission acts in a diversified manner according to its policies, where the Maghreb occupies a variable place. There is also competition among the 28 member states, which have divergent geographical priorities: each supports the countries with which it has the strongest ties. ‘’]

Euro-Maghreb relations in the strict sense have gone through several stages. The first trade agreement was signed with Morocco in March 1969, followed in the 1970s by agreements with the other Maghreb countries. During this period, three Maghreb countries (Mauritania, Morocco and Tunisia) joined the WTO (World Trade Organization), while the other two countries (Algeria and Libya) are, to date, only observers.

These first agreements were marked by the protectionism (community preference) of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) and a restrictive management of financial protocols (low amounts, complexity of access procedures, low absorption capacity). This quickly led to friction between the partners.

In the early 1990s, the fall of the Berlin Wall and the implosion of the USSR created a new situation. The former socialist countries of Central and Eastern Europe multiplied their applications to join the Union. In this context, they undertook real economic and political transitions from an authoritarian socialist system to a democratic market system. Faced with this new competition, the southern and eastern Mediterranean countries mobilized to demand a revival of Euro-Mediterranean cooperation.

The Euro-Mediterranean Partnership (Euromed) was approved by the European Commission in Barcelona in November 1995. It includes economic cooperation (support for reforms and customs disarmament), extended to the new areas of competence of the European Union (environment, transport, cross-border cooperation) and political dialogue. It has also given rise to several associations (or free trade) agreements between the European Union and each of the countries, notably with Tunisia (1995), Morocco (1996) and later Algeria (2005). The functioning of the partnership is based on a complex institutional framework in which two mechanisms coexist: bilateral – materialized by the conclusion of association agreements – and multilateral.

Within this framework, some progress has been made in the areas of transport and the environment. However, the commercial and security logic, often bilateral (State to State), has prevailed, and the results have been far from meeting the expectations of the countries concerned. This is all the more true since political dialogue has never been established – the European partners are content at best to turn a blind eye to the political evolution of these countries and at worst to support the authoritarian regimes in place for economic and stability reasons.

At the end of 2002, the accession of 10 candidate countries to the Union (8 former socialist countries, Malta and Cyprus) was finalized. Immediately, the problem of relations to be developed with those who are not destined, at least in the short term, to join the Union arises. Faced with pressure, the Union ended up proposing to these countries (6 former Soviet republics and 10 SEMCs) a new European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP), which aims to support and promote stability, security and prosperity in the countries closest to its borders. But with three essential restrictions: no prospect of membership; no freedom of movement for people; and a much lower volume of financial aid than that offered to the candidate countries.

In order to accompany the ENP towards the Mediterranean, in the absence of a large Mediterranean community, a Union for the Mediterranean (UfM) (27) was set up on July 13, 2008, following an initiative by the then French president (Nicolas Sarkozy), reframed by the European Union (notably by Germany). The UfM develops a global, peaceful and economically oriented approach to the whole of Europe and the entire southern and eastern Mediterranean region. Based on dialogue between the member states (28 EU countries and 15 SEMCs), the UfM favors a “project approach” with a regional dimension and promotes partnerships between member countries. In the current configuration of the UfM, the Maghreb occupies a relatively marginal place among the 16 countries eligible for the neighborhood policy (ENP). (28)

The UfM, focused on the “project approach”, remains, however, also based on the reductive logic of “Europe of markets and security”, contrary to what was done with the Eastern European countries, for which the logic of economic and political transition, rather peaceful, was imposed.

However, it should be noted that such an approach differs in many respects from the American “Greater Middle East” project (from Turkey to Morocco, and more broadly from Afghanistan to Mauritania), promoted by President Bush since 2004, which aims to export democracy throughout the region, even if it means resorting to violence. We know the results of this “remodeling” of the Middle East that this American strategy has tried to impose in Iraq, Syria, Egypt, Libya…

Faced with this democratic, powerful, united, pacified Europe, oriented towards the East and cautious with regard to its southern flank, the Maghreb appears all the more fragile since it has been made up of states with little relationship between them since independence. Atomized, marked by the smallness of national markets and although largely open to the outside world (more than 35%, on average), the Maghreb has become complacent in its authoritarian and administered operating rules, acting more often than not in a scattered and piecemeal fashion on the global and European economic scene, with its eyes fixed on the North. As a result, the oft-repeated objectives of building a customs union, a Maghreb market, and then a true Maghreb grouping have not been achieved.

Without cohesion, having failed in all its attempts at unification, the Maghreb has still not realized the hope that the creation of the AMU (Arab Maghreb Union) in 1989 held out to the populations of the five countries. After several decades of independence, the Maghreb countries, despite their many assets, remain marked by all sorts of rivalries fanned by:

The “divide and conquer” policy implemented by the countries of the North, by

The conflict in Western Sahara (since 1975); and by

The brutal emergence of political Islamism and terrorism throughout the region.For these reasons, but also because of the poor development of these countries and the structural adjustment programs imposed on them, the populations of the Maghreb have suffered all kinds of violence. In Algeria, the country most affected by these waves of violence, radicalization led, throughout the 1990s, to a brutal confrontation between more or less well identified armed Islamist groups and an authoritarian government symbolizing the refusal of any democratic and peaceful transition.

The revolts and conflicts spread to the entire southern Mediterranean shore with the emergence of the “Arab springs” provoking both revolts against the authoritarian powers in place (Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, Syria…), and the brutal expansion of Islamist terrorism, especially after the eruption of Daech in Iraq and Syria. These conflicts, in Syria alone, have resulted in more than 450,000 deaths, millions of missing persons, displaced persons and refugees.

In these conditions, the issue of freedom has often taken precedence over immediate economic demands, becoming central in all Maghreb countries. This is why the fractures between the two shores of the Mediterranean are constantly deepening.

Building a free and democratic Maghreb

While it is true that economic and political development in the Maghreb region is first and foremost a matter for each country and each people, the fact remains that the regional situation can be a brake, as has been the case since 1989, or on the contrary a gas pedal of democratic transitions in each country. All the more so since the idea of a “Maghreb of peoples” is an old dream and an ancient claim that is still relevant today. Like what has been achieved in Europe, the Maghrebis are ready to unite in their natural and historical space. This is why the Maghrebi peoples always include the objective of a united Maghreb in their projects of democratic transition.

Of course, in this perspective, the UfM could play a major role, even if its priorities and mode of organization need to be reviewed. Today’s priority projects, although important, have no chance of succeeding unless they are in line with the requirements of the times in terms of economic and political transition, but also regional integration.

In order to better adhere to the realities and requirements of today’s Maghreb, the UfM should also be transformed, in the shortest possible time, into a true Mediterranean community governed, as within the European Union, by democratic, social and environmental standards, without distorting the cultural and religious specificities of the various peoples of the Mediterranean. Within this framework, what could be called a “Mediterranean Democratic Union” would create the most favorable conditions for a rebalancing of the Euro-Maghreb partnership in terms of geography (less towards the East and more towards the South), politics, economics, social and environmental issues – the democratic transition. So that the Euro-Maghreb partnership is finally able to quench the thirst for peace, freedom, progress and social justice that the populations express more and more each day. Then, from a torrent of tears, the peoples of the Mediterranean will be able to make a lake of peace. If not, let us beware: by wanting to reduce the issue to the construction of yet another partnership between Europe and the Maghreb, with a strong smell of oil, a commercial aim and security overtones, some people are taking the risk of a renewed and painful failure.

However, such an economic transition can only succeed if it is accompanied by a profound political change. For economic freedom can only be fully realized in a democratic framework: economic freedom and political freedom are inseparable. Together they form the basis of any democratic transition. In the political arena, we must therefore move away from the timidity that has characterized the Euro-Maghreb partnership. For too long, the partnership has relegated this fundamental issue to the sidelines. In vain, this has not allowed the development of the region, nor its stability in view of the conflicts and tensions that have multiplied. Perhaps Europe has failed over the years to listen to civil society in the Maghreb, contenting itself with meetings with regime officials or their representatives. It is true that when interests are at stake, there is little room for political courage!

In any case, on the side of Europe as well as on the side of the Maghreb, the time is no longer for procrastination or evasions, even less for troubled games: there is no other way than to respond to all the democratic and peaceful demands of the populations and to accompany them, frankly and without ulterior motives, in their peaceful steps towards a future of freedom. Europe has been able to accompany the countries of the East in this direction with the successes that we know. Most of them are now part of democratic regimes and political life is regulated in a peaceful manner. So what are we waiting for to apply the same rules (adapted to the history of each country) to the Maghreb, according to a principle clearly expressed in recent weeks by the Algerian population: “without interference and without indifference“?

Morocco’s bid for ECOWAS, consequence of AMU’s failure

As a North African country, Morocco set out to conquer Africa with a great civilizational heritage. The spread of Islam in Black Africa is a major foundation. Moreover, according to international press reports, the number of Muslims in West Africa is 190 million.

The first contacts between the Muslim world and Africa date back to the eighth century, thanks to Arab-Amazigh/Berber traders who criss-crossed the Sudano-Sahelian zone. Timbuktu, in northern Mali, became, from the fifteenth century, the main focus of Islamic knowledge in the southern Sahara.

The other asset for a better rapprochement between Morocco and Africa is, in many respects, the penetration of the Arabic language in some African languages, including Swahili, the official language of Tanzania also spoken in Kenya, Uganda and parts of Zaire and Mozambique, among others, according to a study by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). “The basic vocabulary of Swahili includes 20 percent of words from Arabic,” Unesco said.

It is necessary to recall, moreover, the Moroccan involvement in the West African region, and throughout Africa, through the participation of the Royal Armed Forces in peacekeeping operations and mediation efforts for conflict resolution. This involvement not only meets the expectations of the United Nations, but also reflects Morocco’s strong political, human, historical, religious, solidarity and economic ties with the rest of the continent and with ECOWAS member countries in particular.

On the geopolitical level, and while the AMU (Arab Maghreb Union) has broken down, Morocco’s integration into ECOWAS will represent, in 2030, a group that will be among the top ten in the world. (29)

After the return of Morocco to the African Union in January 2017, Morocco presented its application to ECOWAS in February 2017. The reasons for this application are multiple. Morocco claims first of all its African identity and its historical, human and religious links with the countries of West Africa.

Indeed, in an era of globalization and consolidation of major powers: China, the United States, India, any country the size of Morocco risks being marginalized if it does not integrate into a significant geographical grouping. ECOWAS, expanded to include Morocco, will be more attractive in terms of trade and foreign direct investment. (30)

For Imru Al Qays and Talha Jabril, Moroccan bid to join ECOWAS is controversial in more than one way: (31)

“Morocco applied to join the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) in February 2017. However, its bid has stalled for geopolitical, legal and political reasons in the face of opposition from powerful and protectionist West African economic actors. Nigeria sees Morocco’s bid as a threat to its influence in West Africa, where it is the de facto regional hegemon. Morocco’s bid has also revived inner ECOWAS tensions between Francophone and Anglophone countries, with the latter still uneasy about Morocco’s stance on the Western Sahara issue. Morocco’s joining the economic and political bloc will require changing ECOWAS treaties, opening up its borders to free movement of labor and ostensibly a change of currency. Morocco’s bid has not been successful, so far, because the West African economic actors also fear that goods imported through Morocco’s free trade agreements with Europe and elsewhere, will flood their market and compete unfairly against them. They also desire to keep tariffs on imported goods as these represent a considerable portion of government income. “

Morocco is already very present in Africa since its exports to the African continent reached 22.1 billion dirhams in 2017, or 9% of total exports, particularly to Senegal, Nigeria and Côte d’Ivoire. Morocco has become the leading African investor in West Africa, which accounts for 64.7% of its total investments in Africa. Moroccan investments in West Africa concern several economic sectors: agriculture, insurance, banking, cement, water and electricity, fertilizers, real estate, mining, pharmaceuticals, and phosphates. A major gas pipeline project is underway that will link Nigeria to Morocco, 4,000 kilometers long, which will cross 12 West African countries, and whose cost is estimated at 20 billion dollars.

Current ECOWAS member countries in West Africa

ECOWAS Heads of State and Government agreed in principle to Morocco’s membership at the Monrovia Summit in June 2017. However, at the following Summit in December 2017, they set up a Committee of Heads of State and Government composed of Togo, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Guinea and Nigeria, to “adopt the terms of reference and oversee the in-depth study of the implications of Morocco’s accession.” With this decision, Morocco’s accession process moves from the more bureaucratic and technical ECOWAS Commission to a political level. The five-state committee must determine whether the decision on Morocco’s accession should be taken unanimously, by consensus, or by a two-thirds majority of member states.

For Riccardo Fabiani, Morocco’s orientation to ECOWAS is undoubtedly the result of a long reflection in the event of AMU’s strident failure: (32)

“This reorientation toward Africa is the outcome of a long process in which Morocco has reassessed the benefits and losses of its previous priority on pursuing trade and investment ties with the European Union and United States. Initially this approach helped Morocco build a domestic manufacturing base. its long-term impact was mixed. First, the integration of former Soviet bloc states in the European Union meant that many companies outsourced or delocalized their production to these new members, instead of Morocco. Second, the end of the Multi-Fiber Agreement in 2004 exposed the Moroccan textile industry to competition from low-cost producers in Southeast Asia. As a result, Rabat’s vertical trade and investment integration with its much bigger economic partners ended up highlighting the country’s weaknesses and led to what some economists identified as a process of premature deindustrialization. With its relatively higher labor costs, lower human capital levels, poorer infrastructure quality, and lower state capacity, Morocco struggled to compete with Asian and Eastern European economies. Morocco’s trade, tourism, remittances and FDI further suffered after the beginning of the Eurozone crisis in 2007 because of the country’s dependence on Southern Europe’s struggling economies. “

Morocco’s entry into ECOWAS will therefore create both challenges and opportunities for the current member states of the organization. They will need to anticipate this change and maximize the gains they can make, while managing, as much as possible, the challenges it poses.

One challenge often highlighted is the possibility that Rabat’s entry into ECOWAS will have a “negative” effect, particularly on fragile productive fabrics, or that it will pave the way for a “massive” entry of European products because of Morocco’s advanced partnership with the European Union.

Clearly, without rigorously measuring the real one-to-one impact, some stakeholders claim that Morocco’s entry into ECOWAS could destabilize it and that it would be to the exclusive benefit of the Sherifian Kingdom. This assertion does not stand up to examination of the provisions of the ECOWAS Common External Tariff, which provides for numerous measures to safeguard the productive apparatus of member countries, which could be implemented if any distortion or serious threat were to be observed from third countries. In addition, ECOWAS itself has decided to create a free trade area with the European Union, including protective measures and a transitional period.

Finally, as Senegalese President Macky Sall so rightly recalled, during a meeting on November 20, 2017 in Dakar, with his country’s businessmen, the African Union is working hard to set up a Continental Free Trade Area which, if it works properly, will, in the long run, de facto render obsolete the protections erected by ECOWAS member states towards other African countries, including Morocco.

In any case, Morocco’s full membership in ECOWAS, which granted it observer status in 2005, will be the realization of a reality, because geographically speaking, it is undeniably in West Africa and economically speaking, its integration into this economic area will be in line with the multitude of agreements and conventions signed and flagship projects completed or underway between the Kingdom, on the one hand, and almost all the countries in this West African area, on the other.

Morocco’s accession to the Community as a full member will certainly be “a boon for both parties“, as the Senegalese Minister of Budget, Birima Mangara, had noted on March 22, 2017, quoted by the daily “Le Soleil“, and will bring a “new breath” to this regional grouping, as declared on May 19, 2017 in Bamako, the former Malian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Sadio Lamine Sow. Still, it is the heads of state who will rule on the Moroccan request during their 51st Ordinary Conference, on June 4, 2017 in Monrovia, Liberia.

The Maghreb today

Half a century after independence, where are the societies of the Maghreb today? In many respects, many dreams have collapsed. The oppression of the colonial powers and the racist contempt of the colonizers have been followed by the repression of authoritarian regimes and the arrogance of the new ruling classes. Some of the underprivileged are turning to Islamism. While many citizens still bet on democracy and on a Maghreb finally united.

What is happening to the Maghreb at the beginning of the 21st century? Why is it impossible to live together in the Maghreb? Where are the forces behind this project? Are the nation-states, as such, ready to respond to this demand for union? Are they listening to the youth and their great anxiety? Can they adapt to the changes in their own society? What is the disposition of the middle classes and elites to accompany this project of union?

This flurry of questions challenges us, but the right answers are not obvious. We are struck by the extreme in communication between Maghrebis. Certainly, executives, scientific and cultural elites are constantly meeting. But this is not enough. The neighborhood is experienced as worrying and dangerous. Very often, political leaders talk to each other with their backs turned. But the chance of a united Maghreb begins with face-to-face meetings.

According to the founding texts of the Arab Maghreb Union (AMU), the countries of North Africa are linked by a community of destiny: geography, history, religion, language. This general political consideration defines an institutional framework for building a strategic pole. But this does not take into account the complexity and heterogeneity of the societies themselves. The united Maghreb constitutes a mere promise, an opportunity, a project, no more, no less. In fact, cooperation is very limited in several areas, including energy (gas, oil, coal, hydroelectricity). And constantly deferred. While the new Maghrebi generations are in expectation and hope.

Here are the neighbors who turn their backs. A self-enclosure that has its reasons, its history, its pathology, and its dose of suffering. What is worrying is the lack of initiatives and decisions that strike citizens, governors and governed. It seems that each one is a victim of an evil whose secret he does not know. Victim of the past and of intellectual misery. What is it that frightens the different neighbors?

Concerning the Maghreb today, Mustapha Dalaa argues that the region is dangerously shaken by so many issues that jeopardise its stability: (33)

‘’Les crises qui secouent les pays du Maghreb arabe se sont multipliées, au cours de la période écoulée, et menacent la stabilité de la région, d’autant plus que ces crises ont des dimensions politique, sécuritaire et économique, avec l’intervention de parties étrangères, telle que la France, dans les conflits en cours dans la région ce qui est de nature à aggraver ces crises.

Si nous écartons la Libye et la Mauritanie, au vu de des spécificités qui sont les leurs, et que nous focalisons l’attention sur l’Algérie, le Maroc et la Tunisie – noyau dur du Maghreb – la région fait face à des scénarios incertains, dont certains pourraient menacer la stabilité des Etats, si les crises ne sont pas contenues avant qu’elles ne deviennent incontrôlables. ‘’

[“The crises shaking the Arab Maghreb countries have multiplied over the past period and threaten the stability of the region, especially since these crises have political, security and economic dimensions, with the intervention of foreign parties, such as France, in the ongoing conflicts in the region, which is likely to aggravate these crises.

If we set aside Libya and Mauritania, given their specific characteristics, and focus on Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia – the hard core of the Maghreb – the region faces uncertain scenarios, some of which could threaten the stability of the states, if the crises are not contained before they get out of hand. “]

Conclusion: A plea for an effective Maghreb Union

The success of the new conception of the Maghreb community must be based on several prerequisites. As a key prerequisite, political alternation should be respected, of a democratic type, and not of a tribal or clan type, and even less of a family type. Tunisia is very advanced on this precise point. However, it would be very difficult to get out of it alone without the implementation of an emergency economic plan. The rise of the social movement, which the Islamists are trying to exploit in collusion with regional actors, could plunge the country into a cycle of violence, as was the case in Algeria in the 1990s and in Libya today.

Security normalization under the leadership of NATO would risk exacerbating latent conflicts. The failure of the Tunisian model would thus confirm the racist media thesis of the “Arab exception”, as developed by the orientalists to whom Edward Said devoted a fascinating book in the 1970s. The so-called “constructive chaos” strategy, put forward by certain neo-conservative circles, has become a possibility today, and is supported by the advocates of security normalization. The latter are exclusively concerned with radical and jihadist Islam without examining its deep roots in institutionalized and moderate Islam, for which the application of “sharica” must remain the credo of all Islamic groups.

The stakes are high for Maghrebi economies and societies whose disunity makes them a little more vulnerable and marginal in the global economy every day. The more the Maghreb is disunited, the weaker its bargaining power with the European Union. The Union would give it more credibility and allow it to assert its own interests. To the asymmetrical links between the Maghreb and Europe, the Maghrebis must respond with integration and South-South cooperation, a fundamental issue for development. There is no question of the Maghreb uniting to better oppose Europe, but it must take up its own challenge.

Moreover, its union must not be achieved solely from the perspective of Europe alone. The Maghreb must be considered from a voluntarist, ambitious and audacious angle, which would consist in shaping a true pole that is progressively integrated, in order to try to weigh on the international chessboard and finally exist on the geopolitical map of the world.

Maghrebis must accept to look at the issue of inter-Maghreb cooperation as a resolutely pragmatic necessity, aiming to ensure stability and prosperity and therefore as playing a role as a shock absorber to limit the effects of the shocks of globalization that are expected to increase. More than ever, the conditions are promising to see the countries of this region overcome the nationalisms and build a region of solidarity and progressive integration.

Economically, the competitive advantages of the Maghreb are colossal. The problem lies less in the absence of resources or comparative advantages than in the way they are exploited or channelled. The complementarity of the economies of the Maghreb countries could indeed generate more than two additional GDP points per year per country. To this end, a new analytical reflection that takes into account a new territorial configuration must be developed. This reconfiguration in the making is the challenge of the constraints of economic globalization and the ICT revolution. This reconfiguration is making its way without our participation. The framework of the nation-state imposed by colonization that the Praetorian power consolidated after independence was not adequate and even less so today.