Deadly conflict in Mozambique’s ruby- and natural gas-rich northernmost coastal province feeds on a mix of colonial-era tensions, inequality and Islamist militancy. To tame the insurrection, Maputo needs to use force, with bespoke assistance from outside partners, and to carefully address underlying grievances.

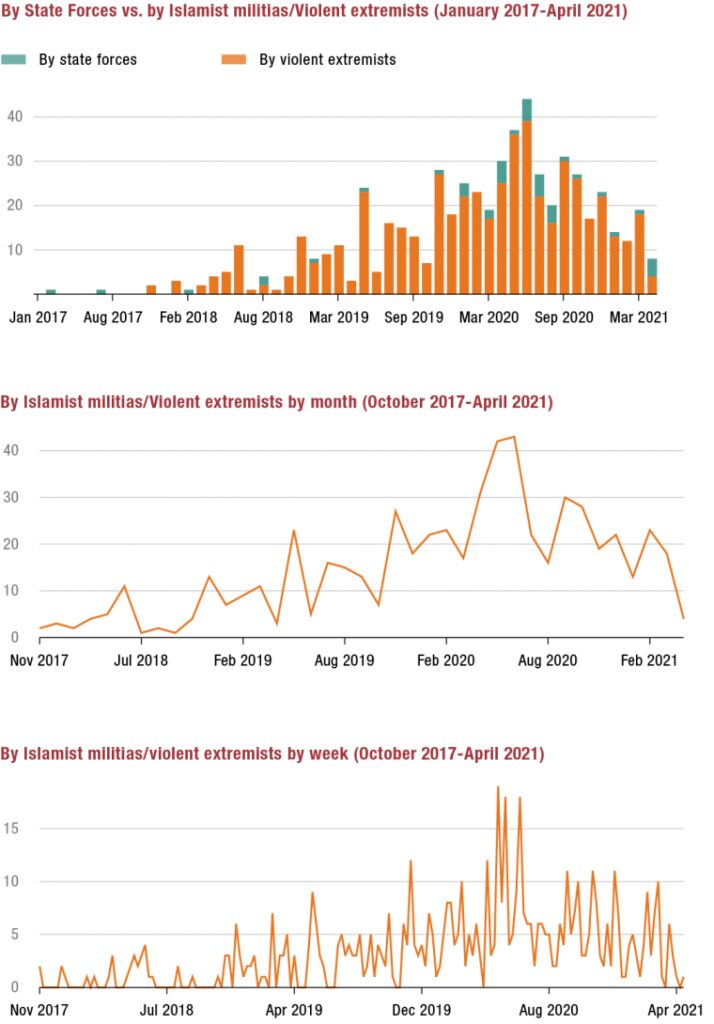

What’s new? Militant attacks and security force operations in Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado province have claimed nearly 3,000 lives, while displacing hundreds of thousands of people. Insecurity has prompted the suspension of a massive gas project. The Islamic State (ISIS) claims ties to the insurrection. Southern African governments are lobbying to send troops.

Why did it happen? Mozambican militants have been motivated by grievances against a state that they see as delivering little for them, despite the development of major mineral and hydrocarbon deposits. Tanzanians and other foreigners have joined up, fuelling the insurrection. The country’s historically weak security forces have been unable to stem the onslaught.

Why does it matter? Unaddressed, the insurrection could spread further, threatening national stability just as Mozambique is fulfilling a peace deal with the country’s main opposition group and heading into national elections in 2024. It could worsen instability along East Africa’s coast and present ISIS with a new front to exploit.

What should be done? Maputo should accept targeted assistance for security operations to contain the insurrection, and avoid a heavy external deployment that could lead to a quagmire. Authorities should deploy aid to build trust with locals and open dialogue with militants. Regional governments should redouble law enforcement efforts to block transnational jihadist involvement.

Executive Summary

Fears are mounting that Mozambique’s Muslim-dominated province of Cabo Delgado could become the next frontier for prolonged jihadist rebellion on the continent. Since 2017, Mozambican militants backed by Tanzanians and other foreigners have thwarted the weak security forces’ efforts to defeat them and perpetrated atrocities against civilians. Thousands have died and hundreds of thousands of people have been displaced. The Islamic State (ISIS) global core claims it is behind the insurrection. While keen to respond militarily, Maputo also needs to deal with the set of local factors that have spurred Mozambican rank-and-file militants into battle. The government should take military assistance from external partners but use force wisely to contain the militants’ expansion while it ramps up efforts to persuade as many of them as possible to demobilise. To that end, it should channel aid to communities and use them and other influencers to open dialogue with Mozambican militants and tackle their grievances. Regional countries should step up efforts to interdict foreign support for the insurrection.

Cabo Delgado is a province that has long been ripe for conflict. In 2007, frustrated youth in the province’s southern districts dominated by ethnic Makua began denouncing the authority of local religious leaders, especially those close to the country’s official Muslim council. By the mid-2010s, ethnic Mwani militants in the coastal district of Mocímboa da Praia had joined the fray. Their activism had an Islamist tinge: they pushed for alcohol bans while opposing the enrolment of children in state schools and the right of women to work. But it was also fuelled by their economic exclusion amid the discovery of rubies and natural gas. They resented, too, the influence of liberation-era generals who have business interests in the province and are drawn from President Filipe Nyusi’s Makonde ethnic group. Amid this boiling resentment, authorities expelled artisanal miners from commercial mining concessions in early 2017, further feeding local discontent. Militants, known to locals as al-Shabab (not to be confused with Al-Shabaab, the jihadist group in Somalia) moved to armed revolt in October 2017.

At first dismissing the militants as criminals, officials now refer to them as “terrorists”. In so doing, they admit the problem is greater than initially thought, but the rhetoric also fuels a perception that global jihadism is the only reason for the threat. Fighters from neighbouring Tanzania, many of whom are part of Islamist networks that have proliferated on the Swahili coast of East Africa are, indeed, among the militants’ leaders. But the bulk of the group’s rank and file are Mozambicans, including poor fishermen, frustrated petty traders, former farmers and unemployed youth. Their motivations for joining and staying with the group are diverse but less shaped by ideology than by desire to assert power locally and to obtain the material benefits that accrue to them via the barrel of a gun. If the group is still growing, it is because it is managing to draw on recruits who see joining and staying with al-Shabab as a good career move. That said, some of the Mozambican militant core may well, by now, be committed jihadists.

Maputo is meanwhile struggling to contain a group that is growing in strength on land and which can also operate in waters off the coast. The army, which significantly shrank after the 1992 peace deal ending the country’s civil war, is in disrepair, a soft target for militants who have overrun many of its positions and plundered its weapons stockpiles. It is also stretched, having to guarantee security in the centre of the country while it tries to achieve the final surrender of a residual armed faction of the Resistência Nacional Moçambicana (Renamo) opposition group. The navy, meanwhile, is barely functioning. Under pressure to respond to the Cabo Delgado crisis, Nyusi dispatched elite paramilitary police units with air support from a South African private military company. This joint force stopped the militants’ advance toward the provincial capital Pemba and destroyed some of their camps but was unable to neutralise them. In March, militants stormed Palma, the gateway to major gas fields, prompting the French multinational Total to halt development.

Mozambique’s government has thus been pressing its foreign partners to provide the resources, including lethal assistance, that it says it needs to build up its military, which Nyusi now wants to be the primary force tasked with fighting militants. Mozambique’s Western partners say they want to help but their diplomats say their capitals will be reluctant to supply materiel to the military without the institution going through significant training and reforms. Those partners are concerned, too, about reports of abuses committed against the population by security forces and potential leaks of government weapons into militants’ hands as a result of alleged graft and indiscipline.

Southern African Development Community (SADC) states, which see Cabo Delgado’s conflict as endangering their own security, are meanwhile seeking to build international support to deploy their own troops into Mozambique. Nyusi has been nervous about that happening. His critics say he wants to keep prying eyes out of the province, a zone for illicit activity including heroin trafficking that benefits elites. His supporters emphasise rather that he is just being careful about what kind of intervention he allows, wary that a heavy presence of foreign troops could become difficult to control and could end up in a quagmire. After the Palma attack, Nyusi, who is currently SADC chairman, has come under further pressure from the regional bloc. He is, however, courting other security partners, including Rwanda, whose troops could be used to provide Mozambican security forces combat support.

Whichever partners he chooses, any external intervention should be measured in how it uses force, so that it can both respond to the very real security threat posed by the militants but also eventually allocate enough resources to protect civilians when they return to their native districts. A heavy deployment of regional troops unfamiliar with the local terrain may not be necessary. Instead, Maputo should welcome bespoke African and international assistance to support its own special forces, who are receiving training primarily from a few Western partners. It should task these special forces to spearhead restricted military operations to contain and then degrade al-Shabab. Patrolling territorial waters could also deny militants opportunities to move fighters and supplies via coastal waters. If residents can be persuaded to return to areas they vacated, Mozambique’s other forces should focus on providing security around these population centres to benefit civilians and humanitarian actors.

A security plan like this would pressure al-Shabab militarily but also leave space for authorities to seek a negotiated end to the conflict. Besides needing to win back aggrieved locals’ loyalty, they also need to induce militants lured by weapons, money and abducted women used as sex slaves to give up violence. Maputo should use its new development agency for the north to start dialogues with civilians in areas where security permits and to work out with them how best to spend donor aid, soothe local tensions and rebuild trust with communities who feel let down by the state. Such dialogue might also help authorities open lines of communication with Mozambican militants, given how deeply al-Shabab’s own recruitment network is embedded in society. If they can reach back this way, authorities could seek ways to encourage the militants’ demobilisation and possible participation in local security arrangements. Maputo may need to offer them security guarantees, and in some cases amnesties, after they exit.

In the meantime, East and Southern African countries should, via their regional blocs, also start exploring how they can conduct joint law enforcement operations to stymie any support to al-Shabab from transnational militants, including ISIS, whose influence over the group appears weak for now. Such operations should focus on stopping attempts by individuals to finance, train or provide new technologies to al-Shabab. Their success will require Mozambique and Tanzania in particular to share information with their international partners about al-Shabab networks that have been operating across their borders.

After more than three years of violence in Cabo Delgado, Mozambique and its regional partners are gearing up to respond together to the threat. They are right to put their heads together. Cabo Delgado’s population craves safety and wants the security forces to act, petrified that otherwise they could end up abducted or killed. A security response is necessary. The government and its allies also need to think carefully, however, about how they can address the grievances underpinning a rapidly expanding challenge that in essence started as a local revolt.

Maputo/Nairobi/Brussels, 11 June 2021

I. Introduction

Once the cradle of Mozambique’s war of liberation from colonial occupation, the resource-rich but impoverished northern province of Cabo Delgado is today home to another conflict critical to the country’s destiny. Since 2017, groups of fighters, often carrying black Islamic State (ISIS) flags and denouncing the state and the Frente de Libertação de Moçambique (Frelimo) ruling party, have grown from small units targeting remote security posts into heavily equipped companies whose attacks threaten not only national stability but also international peace and security. In the last eighteen months, fighters have stepped up raids, including on some of the province’s main towns, resulting in more civilian casualties. Hundreds of thousands of people have fled their homes. Insecurity has also prompted the French multinational Total to suspend a multi-billion-dollar liquefied gas project on which the government hangs its hopes for the country’s future development. Neighbouring capitals now fear the crisis could become a magnet for transnational jihadists who might conduct terrorist attacks in the region.

” Member states of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) are pushing to make some kind of intervention in Cabo Delgado. “

Following the brazen March 2021 attack on the northern town of Palma, gateway to giant gas fields, President Filipe Nyusi is under pressure from regional allies to counter the militants, whom the U.S. now labels part of the Islamic State.

A Mozambican special police unit fighting in conjunction with South African mercenaries was unable to defeat the group. The president is now increasingly looking to Mozambique’s military to do the job. This institution is in a state of disrepair, however, and requires a serious upgrade that will take time. Member states of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) are thus pushing to make some kind of intervention in Cabo Delgado. But Mozambican authorities are wary of allowing in a heavy regional deployment they fear could lead to a messy quagmire. In the meantime, the president has opened a new conversation with President Paul Kagame to assess whether Rwanda’s security forces can provide targeted support.

This report looks at how the Cabo Delgado conflict is unfolding as the country also implements its peace process with the Resistência Nacional Moçambicana (Renamo) opposition group and heads toward the 2024 election, when, as the constitution requires, President Nyusi must step down after two terms in office.

It offers ideas about what foreign military intervention should look like and concentrate on if it does go ahead. It also proposes other ideas about how to reverse militants’ gains and defang the insurrection. Research involved interviews in February and March 2021 in Maputo and Cabo Delgado with government officials, diplomats, humanitarian workers, security sources, businesspeople, religious and community leaders, politicians and victims of violence. Additional research took place in South Africa, and via remote interviews with sources in Tanzania, East and Southern African countries between December 2020 and May 2021.

II. From Grievance to Insurrection

A. A Province Ripe for Conflict

Separated from Maputo by some 2,000km of coastline, Cabo Delgado is a province whose political economy has been shaped by the war of independence and its aftermath. Following the end of Portuguese rule in Mozambique in 1975, senior Frelimo liberation-era figures drawn from the Makonde tribe prevalent in the province’s northern plateau claimed top positions for themselves, including provincial governorships, while placing their allies in national administrative and military posts as a reward for their central role in the struggle against colonial occupation.

The fifteen years from 1977 to 1992 saw illicit trade proliferate in Cabo Delgado, as local elites enriched themselves by smuggling timber, precious stones and ivory, without being encumbered by the government in Maputo or affected by Frelimo’s war with Renamo, which barely touched the province.

Since the 1990s, the province’s economy has only become further characterised by forms of monopoly and illicit activity, much of which ties back to senior Frelimo figures and their business allies. As the civil war receded into memory, senior Makonde continued to dominate Cabo Delgado’s politics and economy. Over the next years, top Makonde generals who had been key figures in the liberation war, including those who went on to serve as governors, began focusing on expanding their business interests in the province. These included forestry, mining and transport operations that were often backed by state loans.

In the same period, Cabo Delgado’s remote coastline also became a documented hotspot for the import and transhipment of heroin and other narcotics via cartels run by Mozambicans of South Asian descent who received protection from Frelimo’s uppermost echelons at both the provincial and national levels. The proceeds from such illicit trade washed through the political system, keeping Maputo content with the status quo in Cabo Delgado.

Senior Frelimo officials acknowledge that the ruling party and the post-liberation governments in Mozambique did not transform Cabo Delgado’s war economy. They admit being preoccupied with areas nearer the capital. “We paid a lot of attention to the development of the regions of the south and the central part of the country where the war with Renamo took place, but in so doing we also have to take the blame for having neglected Cabo Delgado”, said a top Frelimo official in Maputo.

While poverty certainly aggravated local tensions, some socio-economic indicators are worse in other northern provinces. Other factors helped make the province ripe for conflict.

Mozambican social scientists suggest that colonial-era tensions between the Mwani and Makua peoples, on one side, and the Makonde, on the other, have grown since liberation and now shape conflict dynamics. They say, however, that these tensions are political rather than inherently tribal. Many Mwani, alienated by the dominance of the Makonde elites after independence, have remained sympathetic to Renamo and, with a large number of Makua, have become a major source of recruits for the insurrection. In the words of one senior government official working in Cabo Delgado: “What has happened is essentially a protest against socio-economic asymmetries and inequalities”.

B. Religion as a Conflict Vector

Young people’s anger at inequality and their political exclusion bloomed in the post-war period, which was also marked by a period of change for Islamic denominations active in Muslim-dominated Cabo Delgado. On this front, two trends were visible.

First, in the late 1990s, came the return of Mozambican students who had been sent abroad to study by the Islamic Council of Mozambique (Cislamo), a Salafi denomination that had allied with Frelimo in the 1980s, when the party was looking to co-opt segments of the Muslim community and broaden its connections to Arab states.

The return of these young men, who had studied in Egypt, Libya, Algeria, Sudan and Saudi Arabia, was part of a pattern of growing Salafi influence in Mozambique and financed by foreign states and charities. With the influx of devotees and cash over the next decade came a new circuit of mosques and madrasas built across the Muslim-majority north, including Cabo Delgado. This trend challenged traditional Sufi orders that had long dominated coastal enclaves, and areas deep in northern Mozambique’s interior, and whose practices had adapted to local customs over centuries.

” Even as newer religious establishments in Cabo Delgado propagated more doctrinaire Islamic practices, youth in the province’s coastal areas were consuming other religious teachings prevalent on the Swahili coast of East Africa, where Islamist and jihadist networks had proliferated since the 1990s. “

Secondly, even as newer religious establishments in Cabo Delgado propagated more doctrinaire Islamic practices, youth in the province’s coastal areas were consuming other religious teachings prevalent on the Swahili coast of East Africa, where Islamist and jihadist networks had proliferated since the 1990s.

Some of these young men, including petty traders, had established commercial and other ties up the coast via the small caucus of smugglers and merchants from Tanzania, Kenya and Somalia in Cabo Delgado’s port of Mocímboa da Praia with whom they together formed both business and religious associations. These groups in turn helped disseminate pamphlets espousing the propaganda of Aboud Rogo, a Kenyan cleric who before his assassination in 2012 was associated with al-Qaeda’s East African networks and Somalia’s Al-Shabaab movement. Rogo had become something of a cult hero in Kenya after his arrest in 2002 and acquittal in 2005.

By early 2007, early signs of local militancy appeared in Cabo Delgado, particularly in the Makua-dominated areas of the province’s south and south west. Religious and communal leaders from Cabo Delgado describe aggressive behaviour by youths who began challenging the established Sufi religious orders and Cislamo in these districts, accusing both of acquiescence with the authorities.

They also began trying to block the enrolment of children in secular schools and accusing local religious leaders, including those from Cislamo, of hypocrisy and apostasy. Dressed in shortened trousers, in fashion among their East African brethren, and occasionally brandishing knives, they began setting up their own prayer houses or informal mosques in private residences in different villages. Local authorities often confronted these youths, arresting them before releasing them for lack of formal charges.

Frelimo officials, local religious and communal leaders and scholars of Cabo Delgado explain that despite their many attempts to flag these developments within the party and to local officials, the government never developed a strategy to deal with this emerging problem, besides the mass arrests.

While on one level, the crisis appeared to be a sign of Islamist militancy on the rise, it was also a rebellion of primarily Mwani and Makua youth in a province with a Muslim majority against local Sufi religious leaders and an organisation, Cislamo, which they saw as one of the Frelimo state’s closest allies.

C. A Resource Boom Lights a Fire

” A rich deposit of rubies was discovered in the western district of Montepuez in 2009, followed by giant reserves of natural gas in the seabed off Palma. “

The tensions in Cabo Delgado appeared to heighten after 2009, as the state earmarked the province as a future source of mining and hydrocarbon revenue. A rich deposit of rubies was discovered in the western district of Montepuez in 2009, followed by giant reserves of natural gas in the seabed off Palma. Beginning in 2010, the state cleared residents off the land it eventually allocated to the mining and hydrocarbon concession holders.

A top Makonde general who says he had previously acquired rights to the land around the deposit entered a partnership with an industrial miner, generating feelings of exclusion among mainly Makua communities living near the new concession. While locals around the gas development near Palma secured relocation packages from the multinational companies, many complained about those deals’ lack of transparency, the loss of their livelihoods as they were displaced, and lack of access to job opportunities with the oil and gas operations.

Frelimo’s choice of Filipe Nyusi as its candidate for the 2014 presidential election was meanwhile a sign that the old Makonde heavyweights were calling in claims to have the top position in government allocated to them. Some senior party members say an unwritten rule always stipulated that power would eventually rotate into the hands of this caucus, which has waited in line behind a succession of southern presidents since independence.

They also note, however, that the Makonde cohort was particularly keen to take control of the presidency at this moment, as Cabo Delgado was emerging as the epicentre of Mozambique’s resource bonanza. In the end, the choice of Nyusi, a younger Makonde, represented a tense compromise between the caucuses loyal to the Makonde generals and the outgoing president Armando Guebuza, who had been seeking a third term of office, and under whom Nyusi had served as defence minister.

The 2014 election, which took place amid a ceasefire between the state and Renamo, was not the cakewalk for the ruling party that previous elections had been.

Nyusi scored only 57 per cent of the vote, much lower than Guebuza’s margin of victory in 2009. The drop-off reflected Renamo’s resurgence at that time but also the divisions within Frelimo that had come to the fore. Nyusi still won in a landslide in Cabo Delgado itself, however. Some Frelimo officials say that even though Nyusi has a strong political following in the north, the party achieved its sizeable victory in the province in part due to its distribution of patronage.

After the elections, Makonde business elites began to show greater bullishness in acquiring economic power in Cabo Delgado. They spread their money around among district Makonde party stalwarts and local chiefs, entrenching the community’s power base down to the grassroots.

State allocations of war veteran pensions in Cabo Delgado also became more heavily skewed to favour Makonde recipients. As a result, working-class Makonde were also able to buy up land in parts of the province, including along the Mwani-dominated coast. Frustration among Mwani youth reignited, particularly as they were also enduring extortion by local officials interfering with their small businesses and fishing operations.

Sources from Mocímboa da Praia report that as these local tensions heated up around the end of 2014, Mwani youth who were known among traders began mysteriously vanishing from the port town. Locals reported that some of them had in fact travelled to countries up the Swahili coast of East Africa and even farther afield. This trend was matched by a wave of migrants landing at Mocímboa da Praia, a mix of other Mozambicans and foreigners.

Sources working in the town’s banks at that time report that substantial amounts of money flowed into Mocímboa da Praia from Somalia and elsewhere.

By 2015, reports were proliferating about increasingly aggressive behaviour by the same youth gangs clashing with religious authorities in several Cabo Delgado districts. In the first instance, scuffles broke out between them and local leaders, as they became even pushier, for example by attempting to impose bans on alcohol, disrupting prayers at mosques, forcing women to wear the niqab or burqa and preventing women from working outside the home.

As they clashed with local government and religious officials, the state began to fight back. Security forces arrested groups of youths and closed their prayer houses. By 2016, sources in Cabo Delgado were reporting armed elements establishing a presence in remote parts of Mocímboa da Praia district.

” Since the discovery of the ruby deposits in 2009, thousands of prospectors from elsewhere in Mozambique or Tanzania and other parts of Africa had arrived in the area to search for gems. “

The authorities stoked further discontent in early 2017, when they expelled thousands of artisanal miners digging in the ruby fields under the commercial concession near Montepuez. Since the discovery of the ruby deposits in 2009, thousands of prospectors from elsewhere in Mozambique or Tanzania and other parts of Africa had arrived in the area to search for gems, often coming into confrontation with police and mining security guards patrolling the concession on behalf of the industrial operation.

Those lucky enough to evade the guards and find rubies sold them to Tanzanian, Thai and Sri Lankan buyers in Montepuez but also, in smaller quantities, to traders in Mocímboa da Praia. The authorities however eventually kicked out thousands of miners and traders, both foreigners and Mozambicans. The expulsions, which were violent, also thus deprived some of the Mwani and foreign traders in Mocímboa da Praia of an income stream. Several former miners joined the militants. “This was now war against the Makonde top dogs behind the concession”, says one former miner.

By now, militant youths across the province were trying to come up with a name for themselves. Some referred to themselves as members of Ahlu Sunna Wal Jammah, which literally translates as the “adherents of the Prophet’s words and deeds and the community of his followers”. This name never gained traction, however.

Both militants and locals instead began using the label al-Shabab, Arabic for “the youth”, although not in any way to suggest that the group in Mozambique was linked to the separate Al-Shabaab insurgency in Somalia.

III. Local Insurrection to International Crisis

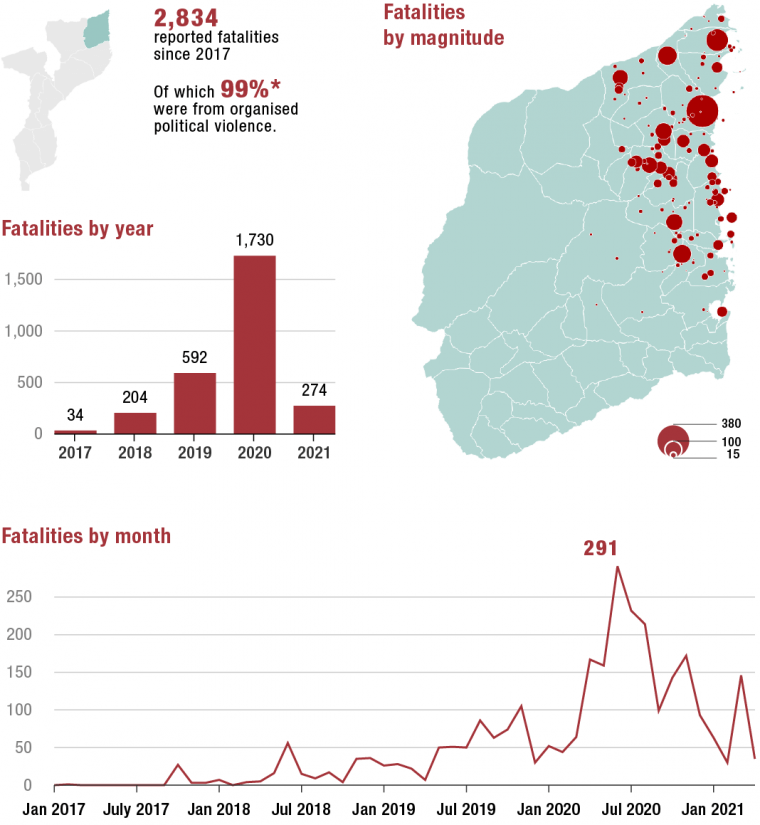

An armed phase of the insurrection soon started. It would accelerate into a humanitarian catastrophe and threat to regional stability. Almost 3,000 people would lose their lives and hundreds of thousands flee their homes and native districts in the next three and a half years of conflict.

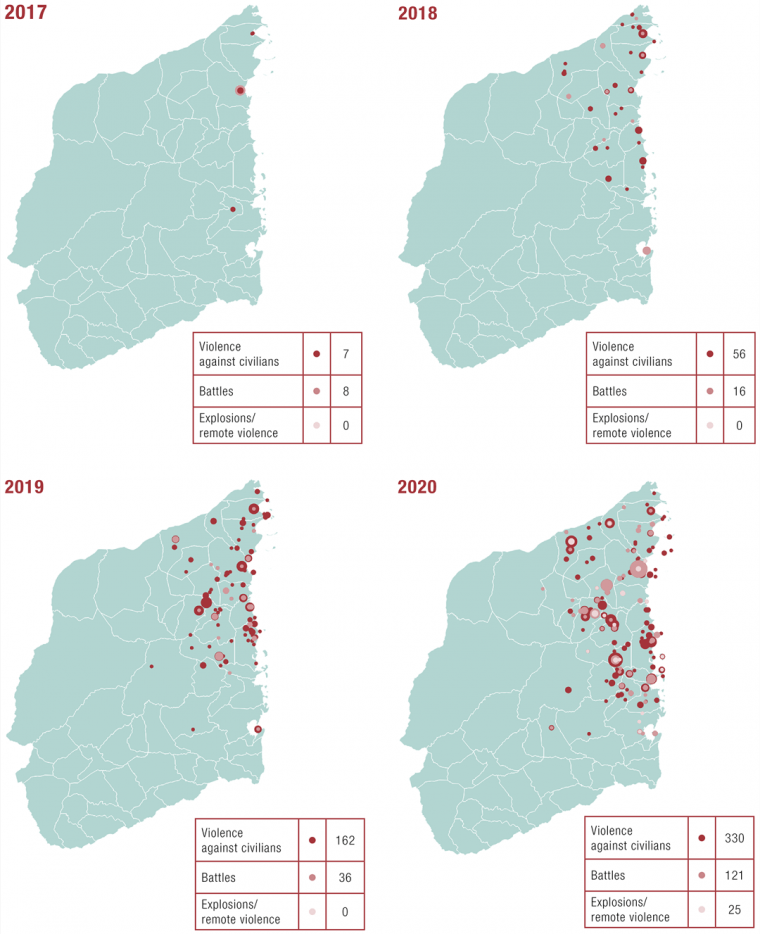

A. The Early Phase: Moving Inland from the Coast

The violence in Cabo Delgado started in the port town of Mocímboa da Praia and quickly spread. On 5 October 2017, around 30 fighters stormed the town’s police stations, raided their armouries and battled security forces for more than a day, leaving more than a dozen dead, including several of their own number.

Residents who encountered the fighters just prior to the assault said they wanted only to attack the state and not to pay taxes. Three days later, security forces had retaken the town. Over the rest of the month, however, militants mounted additional attacks on security forces nearby. They also raided the coastal town of Olumbi, some 70km north toward the town of Palma, the gateway to the major gas project on the Afungi peninsula, then run by the U.S. multinational Anadarko.

Security forces hit back with mass arrests and counterattacks, but in so doing stoked local grievances further. They first began arresting suspected militants and collaborators, eventually detaining hundreds.

In December, they mounted an air, land and sea attack on the village of Mitumbate, near Mocímboa da Praia town, understood to be a militant stronghold at the time. The attack reportedly killed a substantial number of al-Shabab fighters, but also sparked anger from residents who claimed that women and children had been caught in the crossfire.

As the militants regrouped, they spent the first few months of 2018 attacking security forces and raiding villages for supplies.

From the middle of May, militants spread farther south into coastal districts of Macomia and Quissanga, and faced little resistance from security forces, leaving civilians to suffer dreadful abuses.

Al-Shabab fighters reportedly beheaded ten civilians in Palma district in late May. During the course of June, militants also raided villages in districts already under their influence where they burned homes and hacked people to death, forcing thousands to flee. In July, they also made bold raids against security force posts in Mocímboa da Praia and Palma districts, capturing their weapons.

By late 2018, al-Shabab fighters had come to dominate the four main districts accounting for most of Cabo Delgado’s coastline but also begun moving inland. Between November and the end of December, militants stepped up raids on remote villages across the districts under their sway, particularly Palma and Macomia, but also farther inland in Nangade and Muidumbe, both of which have significant Makonde populations.

As the crisis entered 2019, militants began to show more confidence in engaging state security forces and ambushing transport routes in the coastal districts. On 21 February, they attacked separate Anadarko convoys in Palma district, killing a company contractor and sending alarm through the gas industry.

In April, fighters raided a military base in Mocímboa da Praia district, reportedly making off with a significant quantity of weapons. With the province reeling from Cyclone Kenneth, militants continued to resist security forces’ attacks. In early June, they beat off an operation in Mocímboa da Praia. ISIS propaganda channels celebrated the counterattack, saying the fighters were “soldiers of the caliphate”. After security forces reportedly killed 26 fighters in Nangade district in mid-June, the militants rebounded with attacks on police and killings of civilians, including more beheadings, in several districts.

B. Security Forces Turn to Military Contractors

Following battles between al-Shabab fighters and security forces in Macomia and Palma districts in July and August, militants started moving again into the Makonde heartland of Muidumbe district. Alarmed, authorities contracted the Russian Wagner Group to support operations through October, diverting the mercenaries from their original duties of providing security for the presidential election, which Nyusi won in a contested vote criticised by international observers and marked by a dip in his popularity in Cabo Delgado.

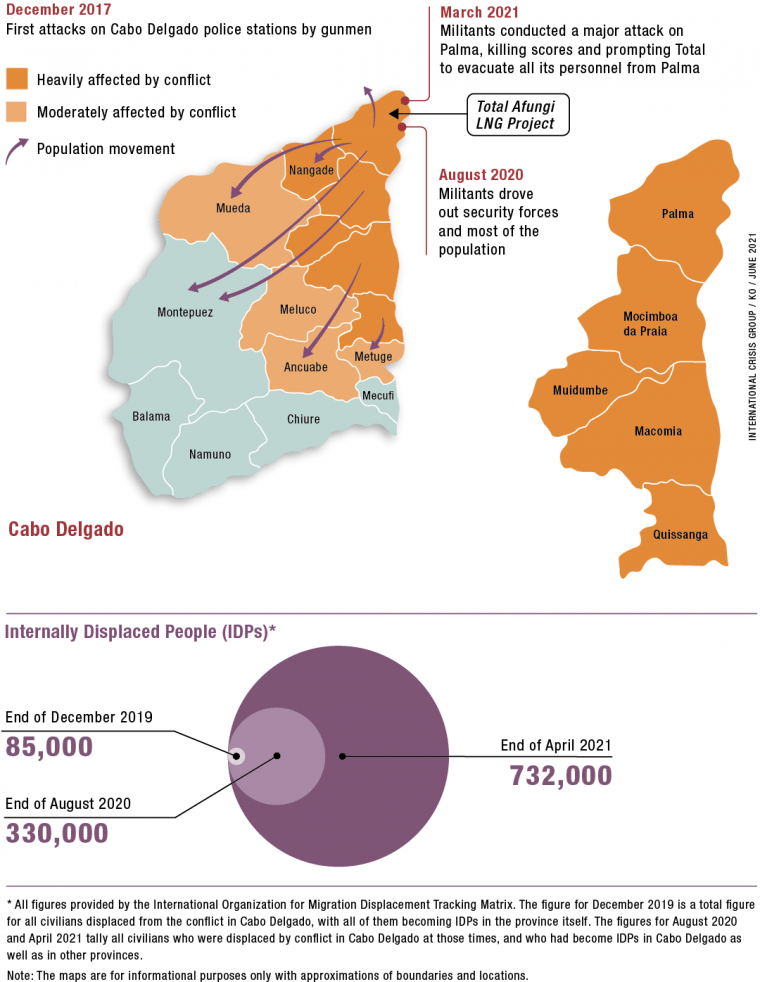

While killing several militants, the Russians sustained losses of their own and wound down operations. For the rest of 2019, militants thus had more room to operate. They made incursions into Tanzania in November before stepping up raids again in Muidumbe district in December. By the end of December, 85,000 civilians in Cabo Delgado had fled their homes.

With the onset of 2020, the militants became better organised and equipped, forming at least three geographically separate attack groups, in the north, centre and south of Cabo Delgado.

They could now mount multiple operations in different areas on security services and state infrastructure. In late January, al-Shabab fighters first attacked Mbau in Mocímboa da Praia district, reportedly killing more than twenty soldiers. They then raided the town of Bilibiza, in Quissanga district, a few days later, vandalising government buildings including a health centre. Thousands of people began fleeing southward amid sporadic cholera outbreaks. Humanitarian and other sources report that during this time, al-Shabab fighters who came across civilians during the course of attacks began ordering people to vacate land or be killed.

Militants then launched bold raids on district capitals as the COVID-19 pandemic arrived. In March, in the first attack against Mocímboa da Praia town, they battled security forces, overrunning a military base, before raising the ISIS flag and handing out food to civilians applauding them.

The militants left town a day later, having kidnapped a large number of women and children. A separate group of fighters then attacked Quissanga town, destroying the police headquarters, burning the military barracks and beheading the statue of Eduardo Mondlane, Frelimo’s founder. In early April, al-Shabab also mounted sustained attacks on Muidumbe town, otherwise known as Namacande, decapitating or shooting dead dozens of nearby villagers before retreating from helicopter gunfire from the Dyck Advisory Group, a South African private military company brought in to support Mozambican forces.

” Maputo’s decision to use the mercenaries arguably dented al-Shabab’s momentum. “

Maputo’s decision to use the mercenaries arguably dented al-Shabab’s momentum, but even when pushed onto the back foot, militants quickly regrouped.

A few days after their retreat from Muidumbe, they raided the island of Quirimba, in Ibo district, where they destroyed a school, a health centre and an administrator’s residence. Security forces and Dyck men counterattacked in April and May, reportedly killing dozens of al-Shabab fighters. Militants still managed to mount a bold attack on Macomia town, storming into the district capital carrying rocket-propelled grenades and wearing government army uniforms. Humanitarian workers and many civilians abandoned the town. Government security forces attacked al-Shabab positions days later and again in mid-June, with officials reporting dozens of militants killed.

The militants would, however, rebound again.

C. The Onset of an International Crisis

In late June, al-Shabab fighters launched a multi-pronged raid on the port town of Mocímboa da Praia, attacking government and police buildings and killing civilians and security force personnel.

Days later, the joint government and mercenary force struck an al-Shabab base in Quissanga district, with officials claiming they killed a large number of al-Shabab fighters. Still, the militants bounced back again. After a spree of raiding and looting in Macomia district, they made another assault on Mocímboa da Praia town, driving out security forces and almost the entire population in more than a week of fighting in early August that left dozens dead. By the end of the month, the total number of displaced people had risen to 330,000.

Regional capitals and oil and gas multinationals began to fear that the situation was getting out of hand. In August, during the assault on Mocímboa da Praia, neighbouring Tanzania had announced that it would step up border security operations. The French oil and gas multinational Total, which had purchased Anadarko’s assets in Africa in 2019, pressed the government to enter into a new memorandum of understanding that obliged the government to reinforce its security force presence around the Afungi perimeter.

The company’s chief executive officer, Patrick Pouyanné, travelled to Maputo to meet Nyusi, to whom he relayed that the risk posed to the company’s multi-billion-dollar operational plan was becoming critical. Still, the militants continued to sustain the momentum. Weeks later, in October, a group of al-Shabab fighters numbering as many as 300 crossed into Tanzania and raided security, reportedly capturing military equipment in an attack again celebrated by ISIS.

The conflict started to draw world leaders’ attention and prompted Total to start reducing its operational footprint. In late October, Dyck helicopters struck two boats carrying militants off the coast of Ibo district.

Days later, security forces struck militants again, this time in Palma district. At the same time, al-Shabab massacred up to 50 civilians in Muidumbe district before eventually storming Namacande. UN Secretary-General António Guterres and French President Emmanuel Macron strongly condemned the killings. The then-outgoing U.S. coordinator for counter-terrorism, Nathan Sales, visited Maputo, where he insisted to journalists that the militants were part of a “committed ISIS affiliate that embraces the ISIS ideology”. In December, al-Shabab fighters attacked security forces close to Afungi. Although these strikes did not target Total, they still prompted the multinational to withdraw non-essential and non-security personnel the following month and press the government to provide more troops to secure the Afungi perimeter.

After security forces and Dyck hit a militant base in Mocímboa da Praia district in February 2021, many in the private security industry speculated that the militants would struggle to recover.

But the militants geared up operations in the north, drawing from their bases on the Tanzanian border. They began raiding the environs north of Palma town. The raids sent waves of terror through the civilian population, thousands of whom fled the district as food supplies reached critically low levels due to lack of secure road access.

On 24 March, militants numbering around 120 and heavily armed with machine guns and grenade launchers attacked Palma town, destroying government buildings, robbing a bank, raiding arsenals and forcing tens of thousands of people to flee. As fighting with security forces spilled into a second day, a second group of attackers moved in from the north. They razed large parts of the town, killing civilians, and ambushed a convoy including expatriate contractors who were trying to flee. Rescue operations shipped thousands of civilians by boat to Pemba, as security forces battled the militants. On 27 March, Total announced it was halting operations. ISIS then celebrated the attack on its media channel.

In the days ahead, government forces continued to fight militants, amid sporadic attacks on security forces around the perimeter of Afungi. Authorities declared they had taken back control of Palma on 4 April. By then, however, Total had decided to withdraw all its staff from Afungi.

On 26 April, the company invoked force majeure, saying it would no longer be able to guarantee its contractual obligations to the state. By the end of the month, the total number of displaced people from Cabo Delgado had risen to 732,000.

Since late April 2021, al-Shabab’s activity has been relatively muted while government and allied forces put them under pressure in continued cat-and-mouse operations. Militants continued to raid neighbourhoods of Palma, forcing civilians to flee during the course of early May, before moving their attention south and west toward Muidumbe, Mueda and Nangade districts where they once again began to mount attacks. Government forces, however, have been able to take back some strategic locations, notably Diaca, an important gateway to Mocímboa da Praia, as well as Namacande, which had been dominated by militants since November 2020.

They have also attacked militant positions in Macomia district.

IV. Al-Shabab’s Evolving Shape, Strength and Behaviour

Cabo Delgado’s al-Shabab is a composite movement. Lower-level militants are mostly Mozambicans, primarily young Mwani and Makua who tend to be former fishermen and farmers, coastal smugglers and traders, or unemployed youth.

There are a small number of Makonde al-Shabab fighters, for example some who were swept out of ruby mines in 2017. But the leadership of the movement is different. While there are a number of known Mozambican leaders of al-Shabab, eyewitnesses and Mozambican officials say Tanzanian Islamists, many of whom fled into Mozambique after security crackdowns in their home country in recent years, represent an important part of the group’s leadership. These men appear to be more ideological than the Mozambican rank and file, many of whom are abducted and forced to sign up, or who join al-Shabab out of frustration with their socio-economic status, lured in by recruiters either offering cash or promising future wealth, and staying loyal to the group so long as they are paid.

The movement seems to be growing in strength even after sustaining many casualties. It has reoccupied some of the main bases previously attacked by security forces. Independent security sources say the group comprises up to 1,500 fighters, but some government officials think there could be as many as 4,000 members, including in non-combatant roles.

Eyewitnesses describe the group’s logistical crew, which include local mechanics, nurses and communications specialists. The group recruits those it can entice with money, or the promise of it, as well as by kidnapping men in raids. Ever more evidence suggests that al-Shabab cells are recruiting in neighbouring Niassa province to the west and Nampula and Zambezia provinces to the south. When attacking major population centres, the group is thus now able to amass relatively large units. Hundreds of fighters were involved in the August 2020 battle in Mocímboa da Praia town and in the March 2021 attack on Palma town, for example.

Since 2017, the group’s weaponry and operational tactics have also improved significantly. According to a range of security sources, militants have significantly built up their armouries, including from stockpiles they have grabbed directly from government armouries.

Dependent at first on AK-47 rifles and the occasional PKM machine gun, they have now acquired racks of RPG-7 rocket launchers and several 60mm and 82mm mortar firing systems, as well as the occasional government vehicle, mostly from looting security forces. On land, the fighters have become adept at coordinating simultaneous attacks in different districts and have got markedly better at battlefield tactics. In addition, they are mobile in littoral waters, using small canoes and sailboats to move up and down the coast or to mount attacks on shore or nearby islands.

” Al-Shabab’s militants have developed cells not just among the civilian population but also within armed force units. “

They also appear to have built up an effective intelligence system. Security sources report that the militants have developed cells not just among the civilian population but also within armed force units.

They have caught security forces flatfooted in ambushes and prepared raids on military bases from nearby hidden locations as well as infiltrated towns before launching attacks, as they did in Palma. Fighters often attack areas soon after security forces depart, suggesting that they have advance knowledge of their foes’ movements. When they attack, they sometimes wear security force uniforms, obtained illegally, confusing civilians and soldiers who are unable to tell whether they are in fact al-Shabab until it is too late. The group has also attracted defectors from the security forces. One Mozambican source told Crisis Group that former security force personnel he hires for his security company say they know out-of-work former colleagues who have joined al-Shabab.

The militants also appear able to generate considerable revenue and deploy funds to expand their operational footprint and recruitment base. Some businesses in Cabo Delgado pay protection money; other enterprises have been started up through cash loans from militants, who then tax profits.

Militants also raise revenues from ransom payments. Intelligence sources suspect significant funds may be channelled in from abroad. The funds of al-Shabab are hard to trace, however. The movement often uses civilians to launder money, including via mobile phone transfer services. Eyewitnesses, however, have seen militants handle large amounts of Mozambican meticais and foreign currency. Some experts fear that the movement could start taking a slice of contraband profits, including via bankrolling networks of gold and gemstone miners and smugglers operating in the province. There are fears militants may also start taxing drug cargoes in transit through waters and coastal land under their control, although there is no visible evidence to suggest that is happening yet.

While invoking Islam, and presenting themselves as jihadists, the militants seem to have specific local motives for killing. They sometimes stress their hatred for the ruling party and target specific local administrative and security officials, or those they consider government collaborators.

In one video, reportedly of the Quissanga town attack, militants wave an ISIS banner, but also make clear that they are rejecting the Frelimo flag. A Mozambican militant in another video says they are fighting “leeches and corrupt people” from “Maputo”. One eyewitness told Crisis Group that when al-Shabab fighters stormed Mocímboa da Praia in August 2020, they killed only civilians who presented government-issued or Frelimo identification cards, sparing others who carried no official documents.

” The relationship between al-Shabab and civilians is fraught. “

The relationship between al-Shabab and civilians is fraught. The militant group behaves like a roving predator, often seemingly appearing out of nowhere to conduct indiscriminate attacks before vanishing again. In the process of targeting security forces and government buildings, its fighters have inflicted terrible casualties on locals, often mutilating and decapitating them.

Militant attacks on the Makonde, who are mainly Frelimo supporters and Catholics, are reportedly often severe. Mwani and Makua civilians, however, have also borne the brunt of terrible attacks, for example during al-Shabab’s gradual sweep through the coastal districts in 2018, or in the group’s assaults on various district capitals. During these attacks, militants often explicitly order civilians to leave their homes and never come back. They kill those they believe are resisting the orders. As a result, vast areas in some of the conflict-affected districts of Cabo Delgado are now significantly depopulated.

That said, militants can, from time to time, show mercy, providing residents occasional food handouts and even safe passages out of the line of fire, and frequently telling civilians whom they come across that their real enemy is the state and not the population.

Despite the group’s elusive nature and its tendency to force many civilians to flee districts in which it operates, al-Shabab recruiters still maintain contacts with communities that chose to remain in the conflict-affected areas, and also among civilians and in displacement camps much farther afield.

V. Transnational Links and the Threat to the Region

As the al-Shabab group in Cabo Delgado has grown, Mozambican and foreign security officials have become increasingly concerned that it could draw in more fighters from overseas, and also become a platform from which ISIS or other foreign militants could embed themselves and sow more insecurity in the region. While the link between Tanzanian jihadists and Mozambican militants is well established, the extent of other reported relationships between al-Shabab and other regional networks, including ISIS, is less clear. That said, Mozambique is right to be concerned about the possibility of transnational support for al-Shabab.

The conflict in Cabo Delgado has already been significantly affected by the proliferation of jihadist networks in Tanzania. Over the last decade, Islamist militants in Mozambique’s neighbour have come into confrontation with security forces there.

In 2013, Tanzanian authorities dismantled a training camp which was linked to Somalia’s Al-Shabaab movement and located near the northern city of Tanga. In 2015, security forces began cracking down on Islamist youth in the Kibiti district, 140km by road south of Dar es Salaam. The youth fought back in 2017, targeting public and security officials in the district only to be met with heavy security crackdowns, accompanied by hundreds of reported disappearances. Many of these youth fled to Mozambique, where they eventually joined al-Shabab, including as leaders of the group. Some of these individuals are connected to gem traders and maritime traffickers who have worked for smuggling rings still operating today between Tanzania and Mozambique, and which have also been previously used to move recruits from Tanzania to Somalia.

Mozambican officials claim that some al-Shabab militants have also gone to fight alongside the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF), a Ugandan militant group that has been involved in killing thousands of civilians and attacking security forces in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). They also say several Ugandans and Congolese have come to fight in Mozambique, travelling via Tanzania, though they offer no precise numbers or any explanation about why these exchanges, which appear to have taken place mostly between 2016 and 2018, might be valuable for either the ADF or al-Shabab in Cabo Delgado.

Information collected outside Mozambique only partially corroborates some of their allegations. A former ADF fighter whose testimony while in custody has been reviewed by Crisis Group says ADF leader Musa Baluku has long been in contact with al-Shabab leaders in Mozambique.

In addition, the former fighter stated that in 2017, a militant Ugandan cleric now in Mozambican custody was involved in recruiting Mozambicans to join the ADF, moving them from Cabo Delgado through Tanzania and Burundi, after which they crossed into the DRC’s South Kivu province and headed to the ADF’s base in North Kivu. In 2018, a group of Mozambicans arrested in the DRC claimed to the media that they were on the way to join “jihad” and had also travelled via Burundi.

Whether recruits are still moving between the eastern DRC and Mozambique is unclear. While Congolese military sources say they suspect more Mozambicans have been training with the ADF in previous years, they cannot confirm the precise numbers in the ADF’s ranks at present, and say they have no other Mozambicans in custody.

Regional security sources therefore believe that even if there was a significant movement of recruits between the DRC and Mozambique, it has now wound up. That said, an organisation working with the Congolese military says it has identified at least one Tanzanian currently in the ADF who has fighting experience in Cabo Delgado. It is investigating the possibility that other Tanzanian jihadists are rotating through eastern Congo and Mozambique.

” Mozambican and foreign security officials are also concerned about Somali jihadists who may also be getting involved with al-Shabab. “

In addition to these links, Mozambican and foreign security officials are also concerned about Somali jihadists who may also be getting involved with al-Shabab. UN investigators have reported to the Security Council that a senior figure from an ISIS-affiliated splinter of Somalia’s Al-Shabaab movement operating in the north of that country’s semi-autonomous region of Puntland has travelled to Mozambique. The team reported in September 2020 that Mohamed Ahmed “Qahiye”, known by regional intelligence sources in East Africa as a military trainer, had passed through Ethiopia on his way to Cabo Delgado.

While the UN investigators did not provide further details, regional intelligence and diplomatic sources suspect that Qahiye went to train fighters in Mozambique.

Meanwhile, fighters of several other nationalities are known to be embedded in Cabo Delgado’s militant ranks. Eyewitnesses who have escaped or been released from militant bases in Cabo Delgado report seeing other foreigners in camp, including fighters with fair skin, and in one case, blue eyes.

Security sources are divided over whether these men could be from Arabic-speaking countries or from the Caucasus, but establishing who and how numerous they are has not been possible. South African law enforcement officers say they are pursuing several leads relating to South African nationals, and other Africans passing through South Africa, who may have established links with al-Shabab in Cabo Delgado.

Counter-terrorism experts and policymakers claim that it is through these foreign links that ISIS is most likely to exert influence. The UN team monitoring the global evolution of ISIS and al-Qaeda reported in 2020 that the Puntland ISIS-affiliated group acts as an important logistical lead for support directed to both the ADF and al-Shabab in Cabo Delgado.

The U.S. State Department which has now classified al-Shabab in Cabo Delgado and the ADF as ISIS-affiliated groups, has meanwhile named the leader of what it calls “ISIS-Mozambique” as a Tanzanian national, Abu Yasir Hassan. He is known to have been involved in the Kibiti violence and is also suspected to have spent time in the DRC, although some security sources suggest he may be dead. But while ISIS now claims joint ownership of the ADF faction run by Baluku as well as the al-Shabab of Mozambique, under the banner of Islamic State Central Africa Province (ISCAP), the U.S. State Department considers the DRC and Mozambican franchises “distinct entities”.

” If there is a relationship between ISIS and al-Shabab, it appears to be more tenuous than official accounts suggest. “

If there is a relationship between ISIS and al-Shabab, it appears to be more tenuous than official accounts suggest. Crisis Group research elsewhere shows that ISIS tends to exploit pre-existing conflicts and mostly provides only limited resources to strengthen the performance of allied factions on the ground, but that these affiliates retain their own command and control and local priorities.

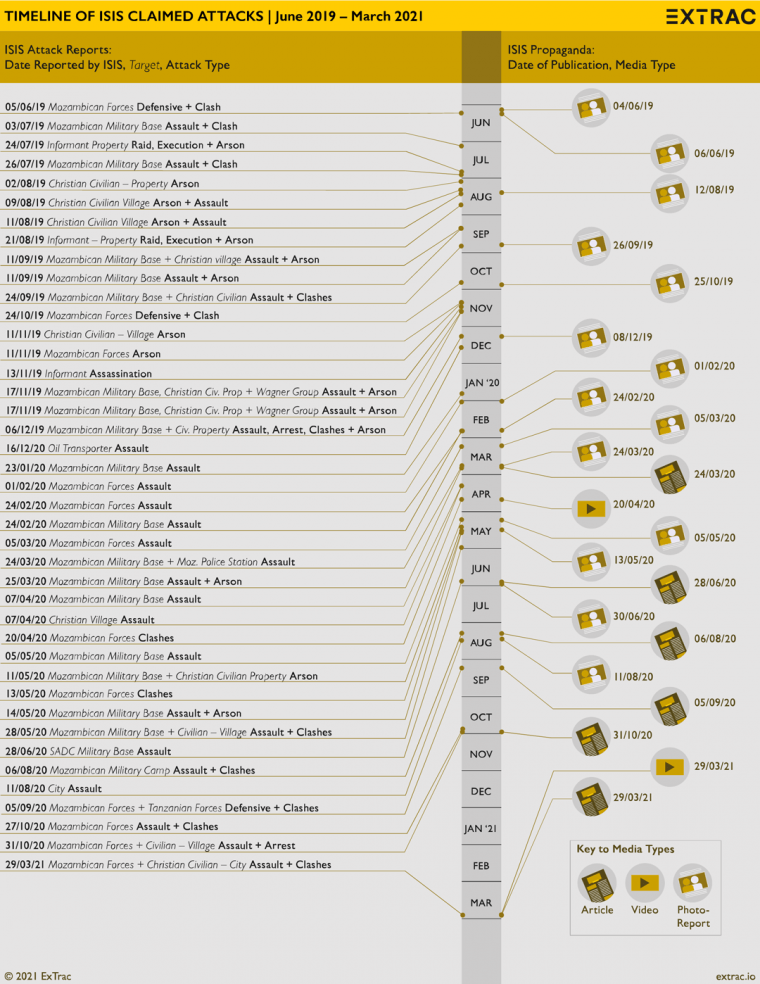

An important indicator of the strength of any link between ISIS and any given affiliate is the speed and accuracy with which ISIS issues media releases glorifying the attacks of the affiliate. Rapid press releases would indicate smooth communication between the groups. In the case of Cabo Delgado, the link appears to be weak. While ISIS has claimed or commented on over 40 separate attacks by al-Shabab between June 2019 and the present, it stopped claiming them at the end of October 2020, resuming only in the aftermath of the Palma attack in March. By contrast, ISIS claims of ADF attacks continued throughout this period.

Regional governments are nonetheless understandably concerned that the longer the conflict rages in Cabo Delgado, the more likely it is that southern Africa becomes a new frontier for jihadist attacks.

In January 2020, South Africa’s Foreign Minister Naledi Pandor stated: “We should be worried, given that the attacks in Mozambique point to the presence of IS in the … region”. South African intelligence and law enforcement officials are also amassing evidence that while homegrown criminal gangs and jihadists in cities like Durban and Johannesburg are mingling with suspected jihadists coming from Tanzania and ADF operatives coming from as far away as the eastern DRC, South African nationals connected to these militant circles have also attempted to travel to Mozambique for combat experience. Authorities are also investigating several suspected ISIS-affiliated money launderers allegedly operating in South Africa.

VI. Government and Regional Responses

A. The Role of the Police and Military

Mozambique’s military, stunted by decades of under-investment, has faced serious challenges when countering al-Shabab and has become a near constant target for militant attacks. The army is also stretched given its responsibilities in trying to achieve the surrender of a dissident residual armed faction of Renamo in the centre of the country.

A special rapid reaction unit of the national police, the Unidade Intervenção Rapida (UIR), supported for several months by Dyck mercenaries until they recently wound down their operation, has served until recently as the primary force taking the fight to al-Shabab.

Mozambique’s national military, Forças Armadas de Defensa de Moçambique (FADM), is in a parlous state after decades of under-investment following the 1992 peace accords that ended the country’s civil war. Much of the FADM’s Soviet-era stock is in disrepair.

Originally slated to be a force of 30,000 men, split 50:50 between government and Renamo appointees, the FADM fell way short in its recruitment efforts, leaving it with just over 12,000 members by 1995, just 30 per cent of them Renamo. Under foreign pressure to prioritise development and loath to trust an institution composed partly of its former battlefield enemies, Maputo continued to slow-roll military spending over the next decades. A government procurement scandal during Guebuza’s term as president and Nyusi’s as defence minister, in which state-backed companies took on more than $2 billion in questionable debt guaranteed by the state to finance the purchase of maritime assets, also rendered the country bankrupt and without a navy fit for purpose.

The UIR has fared differently, however. Spending on the UIR was privileged during and after the Guebuza presidency. This force is better paid and equipped than the FADM and other police units, which also generally suffer from under-investment.

As the crisis erupted, the UIR thus became the main security organ fighting militants. Under Police Commander Bernardino Rafael, the force kept al-Shabab from expanding even further. But Nyusi’s reliance on Bernardino, a Makonde career officer, antagonised those who see him as yet another expression of Makonde dominance in political and security decisions related to Cabo Delgado. Amid these tensions, the UIR had trouble securing ammunition and logistical support from the FADM, hampering its operations in 2020. Meanwhile, Nyusi attempted to involve the FADM further in counter-insurgency efforts by appointing Eugénio Mussa, a prominent military commander stationed in Cabo Delgado, as chief of army staff. This effort stalled when Mussa died in February 2021.

The president has pressed on with his priority of placing the FADM at the heart of the country’s security response.

Maputo has been pushing for more direct bilateral support from its foreign partners, asking them for training and materiel including for the urgent creation of specialised combat units comprised of marines and commandos. After the Palma attack, former colonial power Portugal is expediting the provision of Mozambique’s security forces with an array of specialised training. The U.S., keen to develop a relationship with gas-rich Mozambique, has also reactivated a training program for Mozambican forces. The European Union (EU) is also proposing deploying a long-term training mission of perhaps up to 300 personnel to Mozambique. In terms of equipment, the government has recently acquired armoured vehicles and helicopters from a South African defence and aerospace company, which also has a subsidiary training unit present in Mozambique.

Mozambican officials say they would still need more equipment for units to be deployed effectively against al-Shabab.

Some European and other Western governments are wary of providing Mozambique military hardware to FADM units until they have at least completed their training, citing the allegations of abuses by security forces and government contractors during past campaigns to combat al-Shabab.

External partners also want to ensure Mozambique’s military can maintain such materiel and avoid defectors running off with equipment, or personnel selling it. They also worry about how security forces will manage local militias whom they have relied on to combat al-Shabab, and whether the use of these forces and the distribution of weapons among them by the UIR, FADM or anyone else could constitute another security risk going forward, even if the militias have been useful allies of the security forces until now. Even were the EU inclined to finance the provision of lethal assistance, the European Peace Facility, which is where any financing would come from, is not expected to be functional until July 2021.

B. Promises of Development and Humanitarian Aid

The humanitarian situation in Cabo Delgado is dire. Thousands of people fleeing violence have crammed into Pemba and other towns, stretching public services in the capital and draining the resources of host families.

Thousands more sit in displacement camps in the province’s south and in neighbouring provinces. The government has started to offer many displaced families access to land and services in about 100 new villages in the south, which remains untroubled by violence. It is unclear, however, whether the people installed there can adapt to new livelihoods. Until security improves in their places of origin, there is little alternative, officials say, other than to relocate them to these villages. These villages, however, can only absorb a fraction of the displaced. Aid organisations, meanwhile, complain that government delays in issuing visas and clearing items at customs have stymied their operations across various districts.

As the crisis has unfolded, Maputo has developed plans to draw in hundreds of millions of donor dollars for aid and development projects in Cabo Delgado and the north. In March 2020, the government created the Northern Integrated Development Agency, an institution mandated to coordinate humanitarian assistance and support economic growth and youth employment in the provinces of Cabo Delgado, Niassa and Nampula. The Agency comes under the management of the minister for agricultural and rural development, Celso Correia, a former campaign manager for Nyusi. In April 2021, the government also entered into an agreement to receive $100 million allocated by the World Bank for use primarily in supporting basic infrastructure and livelihood creation for thousands of people displaced as a result of the conflict. The National Fund for Sustainable Development, also part of Correia’s ministry, will be responsible for procurement related to any funded projects, assisted by the UN Office for Project Services.

Questions remain, however, about what role the Agency will play going forward and whether it should not be engaging more directly with the province’s population to survey what people say they need, besides security, in the areas to which they eventually want to return.

Some civil society organisations have expressed concerns that there are insufficient safeguards for how funds will be used, and also worry that there is not enough of an emphasis on using the funds to support the return of civilians to their native districts.

C. Regional Intervention Plans

As Cabo Delgado’s crisis has escalated, neighbouring countries have pushed to get more involved. Southern African Development Community states are keen to put boots on the ground, worried that insecurity could spread north into Tanzania and south toward Mozambique’s central regions bordering Southern African states. But an agreement has been elusive. Critics suggest that the Mozambican president, who is currently SADC chairman, has resisted regional intervention because he does not want to open up Cabo Delgado and its illicit political economy to prying eyes.

The president’s supporters dismiss these views as unfounded assertions, and add that if he has been cautious, it is because he is merely trying to ensure that any foreign intervention is thought through carefully and that Mozambique retains control over it.

The road up to this point has been tortuous. Initial SADC consultations in 2020 delivered little of consequence. The 19 May 2020 meeting of SADC’s Organ on Politics, Defence and Security (also known as the Organ Troika) held in Harare ended with a communiqué saying the bloc was committed to fighting the “terrorists” in Mozambique, but giving no further details.

Two days later, South Africa’s Foreign Minister Pandor stated that Pretoria was “in negotiations” with Maputo to provide assistance, although little, if anything, was agreed.

A meeting of Organ Troika committees in June resulted in commitments from SADC countries to deploy, but without Mozambique’s green light.

Toward the end of 2020, SADC member states became increasingly impatient at Maputo’s hesitation but discussions still yielded nothing.

At a two-day Troika Summit in Gaborone, Botswana, in late November, which was attended by regional presidents (except Nyusi, who was represented by his defence minister, Jaime Neto) the bloc issued a communiqué saying it had “directed” a regional response for the crisis in Mozambique, although it imposed no time frame. Troika leaders (Botswana, Zimbabwe and South Africa) pushed for a follow-up meeting on 14 December, hosted by Nyusi. But further talks on a regional intervention stalled and a decision on SADC assistance was pushed back to a dedicated summit on Cabo Delgado scheduled for 14 January.

That summit was then postponed, ostensibly due to a surge of COVID-19 in the region. Mozambique’s foreign ministry declared on 12 February that a SADC summit might convene in either May or June.

The Palma attack upped pressure on Nyusi. Following the attack, and in his capacity as SADC chair, Nyusi gave in and called an extraordinary “Double Troika” SADC meeting on 8 April where the bloc committed to send a technical team from neighbouring states to Maputo to assess what the regional role in fighting al-Shabab could be.

A day before the meeting, Nyusi stated that Mozambique would lead any military operation involving SADC. “Those who arrive from abroad will not replace us. They will support us”, he said in a state television broadcast. “It’s about sovereignty”. In published closing remarks a day later, he stated that Mozambique would be ready to act “in a coordinated manner and with a support structure and specific regional actions to sustain the threat of terrorism”. Zimbabwe’s ministry of information tweeted that SADC agreed that a force “should be resuscitated and capacitated immediately so that it can intervene”.

Nyusi still appears to be hesitant, worried about whether such a force, were it ever deployed, would be impossible to control.

A leaked report by a SADC technical team recommending the deployment of a combined force of 3,000 personnel in army, navy and air units has already been rejected by Mozambique’s officials, some of whom also feel the leak was a way of putting Maputo under undue pressure to accept a deployment of this magnitude. The follow-up SADC summit of the Organ on Politics, Defence and Security, due to occur on 28 April, was postponed, with South Africa’s President Cyril Ramaphosa tending to a pressing domestic engagement and Botswana’s President Mokgweetsi Masisi indisposed due to a COVID-19 quarantine restriction.

In the meantime, Nyusi has now begun to take advice from Rwanda’s President Paul Kagame on how to manage the military response to al-Shabab. On the same day that the SADC meeting was postponed, Nyusi flew to Kigali to meet Kagame and Rwandan security officials to discuss possible security cooperation. A Rwandan military assessment team followed up with a visit to Cabo Delgado.

Security and diplomatic sources say discussions between the two sides centre around the possible deployment of a small contingent of Rwandan forces who could support Mozambican security forces in counter-insurgency operations. Meanwhile, a follow-up SADC meeting on 27 May again yielded no concrete agreement.

D. Security Cooperation with Tanzania

Ever since the Kibiti crackdowns, Tanzania has been on guard for a resurgence of violence on its own turf. Tanzanian authorities have taken a restrictive approach to border policing, fearing that militants based in Mozambique will cross back and forth at will and stage further attacks on Tanzanian forces. The UN has criticised Tanzania’s policy of either blocking entry for civilians fleeing Cabo Delgado or expelling them back into the province.

A ban on cross-border exports of food into Cabo Delgado in February led to higher food prices and more human suffering in Palma.

” The UN has criticised Tanzania’s policy of either blocking entry for civilians fleeing Cabo Delgado or expelling them back into the province. “

Bilateral relations between Mozambique and Tanzania are cordial but at times strained. In January 2021, Nyusi, Bernardino and Mussa travelled to Tanzania and led to the formal tightening of police and intelligence cooperation between the two neighbours and the extradition of hundreds of suspects in Tanzania to Mozambique.

Yet some Mozambican officials privately gripe that the cooperation is undermined by the Tanzanian security services’ tolerance for smugglers and traffickers, who are in turn connected to the Mozambican al-Shabab and who allegedly receive protection from powerful political and security figures in Tanzania. Mozambican officials say they hope for better cooperation from the Tanzanian authorities under the new presidency of Samia Suluhu Hassan.

VII. Stemming the Insurrection

The Palma attack seems to have focused minds in Maputo and further afield: turning the tide in Cabo Delgado is urgent, lest the humanitarian crisis keep worsening and the insurrection pose a broader threat to national and regional stability. Mozambique’s government has a range of proposals on the table, including the option of inviting in external forces to provide additional security. But it needs to act in a measured fashion, so that security operations are complemented by efforts to address local grievances, in order to avoid what Nyusi himself warns could otherwise become an ineffective and unfocused “salad of interventions”.

A. An Urgent but Measured Security Response

Maputo’s instinct to rebuild the army is sound, but this task will take time. In the interim, the country, already under financial strain from its debt scandal and thus likely to have to depend on external financing to upgrade its forces, will face limitations on how it can combat an enemy that has rebounded with greater ferocity every time it has come under pressure.

” Some military assistance is on its way from Western governments and the EU, but in limited form. “

Some military assistance is on its way from Western governments and the EU, but in limited form. While these partners may be ready to come to Mozambique’s assistance with military training, they have to date demurred from lavishing the country’s security forces with weapons, wary of the human rights allegations surrounding the security services and eager to see the FADM first show greater discipline.

Mozambique is thus in a tough corner. Without capable security forces, Maputo will struggle to stabilise Cabo Delgado and may see al-Shabab plan further attacks and even spread into neighbouring provinces or Tanzania.

External military intervention is thus needed but should be measured. Diplomats, military experts and Mozambican authorities agree that a SADC force of 3,000 troops may well be an unrealistic proposition. Donors fear that the bill for standing up such a force would be prohibitive, given that SADC member state forces have their own capacity and logistical deficits. They also voice doubts that the proposal for this many men is based on a clear strategy; some think it may just be a way for some SADC member states to use the Mozambique crisis to justify international resources for their own militaries.

SADC’s intervention in the DRC already serves as a cautionary tale. Member state forces deployed as an intervention brigade under UN blue helmets in the DRC have for years struggled to finish off the ADF there, with their operations often compromised by poor cooperation with the DRC military authorities. In the meantime, the ADF continues its brutal attacks against civilians.

Security and Mozambican government sources fear that foreign troops with limited understanding of the local environment would similarly struggle against al-Shabab. If they got bogged down in a long conflict, they could attract more foreign fighters eager to take on international forces and turn the province into a battlefield pitting Western-backed forces against transnational jihadists seeking to open a new frontier. Many security experts and some in government are in any case sceptical whether it is possible to eradicate al-Shabab. They believe a more realistic goal would be stemming the militants’ expansion while offering its fighters incentives to demobilise.

Rather than accept a very heavy regional force that risks a quagmire, Mozambique might better benefit from the provision of military advisers, intelligence capabilities and limited but effective combat support from its regional and international partners. Such assistance should be deployed in support of the elite Mozambican commandos and marines that are already being trained up by international partners to spearhead FADM operations against al-Shabab. Donors should be able to extend a limited amount of hardware to these units, with fewer concerns, given the specialised training they are receiving. All contributing parties should agree that these Mozambican forces will lead operations against al-Shabab. Agreements for external combat support should be time-bound so as to allow flexibility in adjusting any mandate or reassigning responsibilities.

” Operations should be geared toward stopping the militants’ expansion and squeezing al-Shabab so that its fighters start to consider leaving the group. “

Operations should be geared toward stopping the militants’ expansion and squeezing al-Shabab so that its fighters start to consider leaving the group. In the meantime, regular FADM units and the police, including the UIR, could secure population centres and provide reassurance to civilians able to return to their districts.

Organising the fight this way achieves three things. First, targeted operations would ensure that the militants are not given free rein to plan more major attacks. Secondly, while operations proceed, Maputo could separately focus on upgrading the broader capabilities of the FADM and police, as they undergo longer-term training. To prepare the ground, Maputo should also conduct a full audit of the logistics base and organisational structures of its military and police forces. An audit would allow Mozambique’s partners to assess what long-term assistance to give – from updating command-and-control systems to improving stockpile management and maintenance skills – so as to help reform and rebuild the FADM and the police. Thirdly, in avoiding heavy external deployment that could turn the conflict into a quagmire, authorities will also have space to use the tool of dialogue to encourage al-Shabab fighters to demobilise.

B. Development, Dialogue and Demobilisation

Knowing that a military solution on its own will not be enough to stem the insurrection, government officials are also keen to use development initiatives as a tool to soothe public opinion, persuade militants to quit al-Shabab and ensure they do not relapse into militancy if they do leave the group as a result of military pressure. Of course, militants may not be responsive to such a bargain if they have become ideologically gripped by jihad, or if they feel their career path within al-Shabab is a better bet.

Officials are also wary they may not have anything to offer harder-line Tanzanian leaders of the group who are not part of Cabo Delgado’s political fabric, and that some Mozambican militants may now be committed jihadists. Still, they and community leaders believe it is possible to appeal to the interests of the vast majority of Mozambican militants who may well consider the option of defecting permanently if the state can demonstrate it is committed to addressing their grievances and keeping them gainfully employed.

Even leaving aside the question of whether militants will be open to such an approach, there are other challenges to using aid in this way. Given the kinship ties between militants and their original communities, government officials believe they can use development funds to rebuild trust with locals and reach back through the communities to al-Shabab fighters to persuade them to defect.

Local activists and staff from the Northern Integrated Development Agency warn, however, that unless aid is channelled into communities through a series of consultations with local populations, it could enflame local tensions, as donors have found out in the Sahel. In addition, unless development spending is all accounted for, it may fuel perceptions that the authorities are not responding to locals’ concerns directly and that funds are being misappropriated.

Various government officials from different ministries and provincial offices are already tasked with consulting local populations, but the authorities should request that this dialogue take place through the Agency, which should identify local leaders who can win the trust of communities and coordinate initiatives to avoid overlap. Nyusi stated as far back as 2019 that he would be willing to initiate dialogue with militants.

The Agency thus has a role to play in terms of kick-starting that process and should work with locals and defectors to find ways of communicating with militants and explaining what they might have to gain by leaving al-Shabab. In addition, the government could then work with other community leaders and figures of influence to keep the dialogue going.