One of the most important problems in modern African history is also among the most widely misunderstood.

For decades, both journalists and scholars have lamented that Africa’s borders were drawn up by outside powers, beginning with Europe’s so-called Scramble for Africa, between 1881 and World War I. This threw all sorts of linguistically, religiously and politically disparate groups into newly formed colonies and, soon afterward, new African nations, in which they were suddenly forced to try to get along together in the task of building independent republics.

The mistake in this logic isn’t that these things didn’t happen. If one allows for lots of historical compression, this is indeed the basic schema that was applied to the creation of almost all of Africa’s 54 countries. The problem with this recounting of Europe’s disruption of Africa’s internal political processes is that it doesn’t reach back remotely far enough in time to capture an even more foundational challenge to the continent’s development.

The original tragedy inflicted on Africa was much graver and farther-reaching than the mere drawing of borders whose logic even now can seem alien and arbitrary from the perspective of hundreds of millions of Africans. An even more profound derailing of the continent was inflicted by Europeans drawn to Africa for the purposes of feeding their slave trades and, later, conquering or deliberately undermining both well-established kingdoms and embryonic African states in order to construct their own rival global empires.

As far back as the 16th and 17th centuries, many parts of the continent were undergoing messy, homegrown processes of conquest and political consolidation by emerging regional hegemons. To name just a few, these included capable and ambitious states like Asante, Benin and perhaps most interesting of all, Kongo, which sent representatives to the Vatican and diplomats to Brazil, and fought alongside the Dutch in an alliance of its own initiation to defeat the Portuguese throughout the South Atlantic. Little remembered today, this story forms an important part of my forthcoming book, “Born in Blackness: Africa, Africans, and the Making of the Modern World.”

In fact, Africa’s indigenous processes of state formation were not so very unlike those of Europe itself at the time, and had they not been derailed by European conquest and the widespread disorder and death fueled by the trans-Atlantic slave trade, one can imagine a very different continent today. Rather than the deeply fragmented Africa we see on contemporary maps, with plentiful micro-states, like Gambia and Togo, and many other desperate, landlocked formations, like Niger and Chad, this might be a world instead where the relatively large and extensive states of that era gradually expanded their writs and absorbed other peoples under a single banner and perhaps under a single, dominant, African language—again, much as Europe did.

If Africa’s internal political processes had continued undisturbed, instead of 54 countries—some of which, because of barren climate, scarcity of resources and geographic isolation, seem destined to forever remain economically unviable, and others of which remain profoundly divided by questions of identity that were codified and often given legal force by European colonists—one can imagine a continent of, say, 25 or 35 nations, many of them more economically viable and sturdy in their sense of themselves.

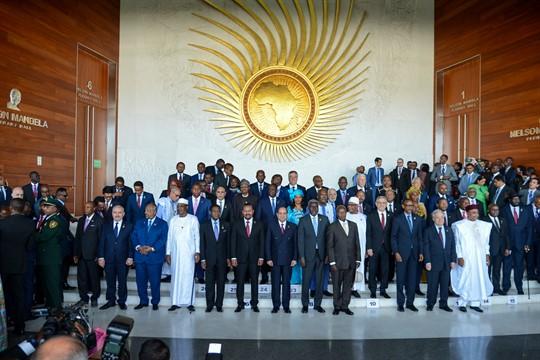

The original tragedy inflicted on Africa was much graver and farther-reaching than the mere drawing of borders whose logic even now can seem alien and arbitrary.History, alas, did not grant Africa the space needed to reach such an outcome. And as ongoing news from one corner of the continent shows, even if it had, many other roadblocks lie on Africa’s path to healthier and more stable political development. Here, the news in question comes from Ethiopia, which, unlike every other country on the continent, more or less constituted its own borders. Ethiopia is Africa’s lone example of an indigenously generated imperial state, and although it eschews the identity of an empire, that now-bygone mode of political order nonetheless best defines its ongoing struggles.

Since the overthrow of its last emperor, Haile Selassie, in 1974, regimes have come and gone in Ethiopia, from a hard-line Marxist dictatorship to a Western-supported authoritarian developmental state to a nominally liberalizing democracy, as the present government of its 2019 Nobel Peace Prize laureate prime minister, Abiy Ahmed, portrays itself. But in each of these incarnations, the state has struggled to retain control over a highly diverse population while holding onto to its vast territory.

Yet, despite laboring to ensure that the center holds, each successive regime has nonetheless lost significant ground. Under Meles Zenawi, who ruled from 1991 to 2012, Eritrea—a territory with its own history of autonomy—gained international recognition as an independent nation in 1993 after a bitter, three-decade-long war with Ethiopia. Under Abiy, since late last year, Addis Ababa’s struggle has been with the region of Tigray and its 7 million inhabitants, whose autonomy-minded leaders Ethiopia has recently fought to bring to heel.

Last week, this culminated in a stunning defeat for one of Africa’s largest and best-equipped armies, as Ethiopian troops were routed by Tigrayan fighters and paraded as humiliated captives by the thousands in the provincial capital, Mekelle.

This is surely not the last shoe to drop, but what shoe will be next? Will the present unstable stalemate between Tigray and Ethiopia brought about by the latter’s cease-fire declaration evolve into an outright civil war and bid for secession? Or will other components of an old imperial confection that remains poorly integrated decide to make their own bids for self-rule, whether the well-armed Amhara of the country’s west or the peoples of the far south, long relegated to an afterthought in both the country’s politics and economic development?

Ethiopia’s uncertain future speaks to Africa’s overriding challenge today: the crisis of its biggest states, few of which can be said to be performing well, and some of which teeter close to failure. Almost 600 million people, or nearly half of the continent’s population, live in its five most populous nations: Nigeria, Ethiopia, Egypt, the Democratic Republic of Congo and South Africa. But in a pattern that has now been in place for most of the independence era, which took off at the start of the 1960s, most of the continent’s bright spots—whether for their good news political stories (think democracy in Ghana) or sustained fast economic growth (in recent years, Rwanda is often touted)—has come from Africa’s relatively small states. Because of their size, they have little impact on the continent’s aggregate fortunes. Finding the right recipe for Ethiopia, or putting Congo or Nigeria on a strong footing, by sharp contrast, would help move the needle for entire subregions—and indeed for the continent as a whole.

As much as it struggles with its imperial legacy, Ethiopia’s leaders have had a hard time renouncing heavy-handed, top-down control, and indeed these two realities—an imperial hangover and lingering authoritarian reflexes—would seem to be closely related.

Abiy surprised Ethiopians and the entire world when he released political prisoners and relaxed police state-type controls on his nation upon taking power, but he has tightened things again since then, ironically moving in this direction after receiving one of the Western world’s greatest accolades, the Nobel Peace Prize, in 2019. He is said to have been told by his mother of a prophecy that he would be a great ruler one day. But being a great ruler in a country as fragmented and complex as Ethiopia may require relinquishing some of the traditional urge for control. The moment for empires has passed, and the choice that looms today would seem to be a federation that devolves more power to its regions under more democratic mechanisms—or a wider breakup of the country into the constituent parts of an old kingdom.