The deployment of Chinese security firms in Africa is expanding without a strong regulatory framework. This poses heightened risks to African citizens and raises fundamental questions over responsibility for security in Africa.

Since 2012, over 200,000 Chinese workers relocated to Africa to work on China’s One Belt One Road (OBOR, yī dài, yī lù, 一带一路), commonly known as the Belt and Road Initiative, bringing the number of Chinese immigrants on the continent to 1 million. There are over 10,000 Chinese companies in Africa, including at least 2,000 state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Chinese SOEs have a major stake in African construction projects, generating over $40 billion in revenue annually.

The Chinese Academy of Social Sciences notes that 84 percent of China’s Belt and Road investments are in medium- to high-risk countries. Three hundred and fifty serious security incidents involving Chinese firms occurred between 2015 and 2017, from kidnappings and terror attacks to anti-Chinese violence, according to China’s Ministry of State Security. This has placed a premium on security to safeguard these investments and a growing demand from executives of Chinese SOEs for a more robust Chinese security presence on the ground. While the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has been averse to maintaining a large presence in Africa due to a host of reputational and logistical factors, China is not confident that African security forces can do the job.

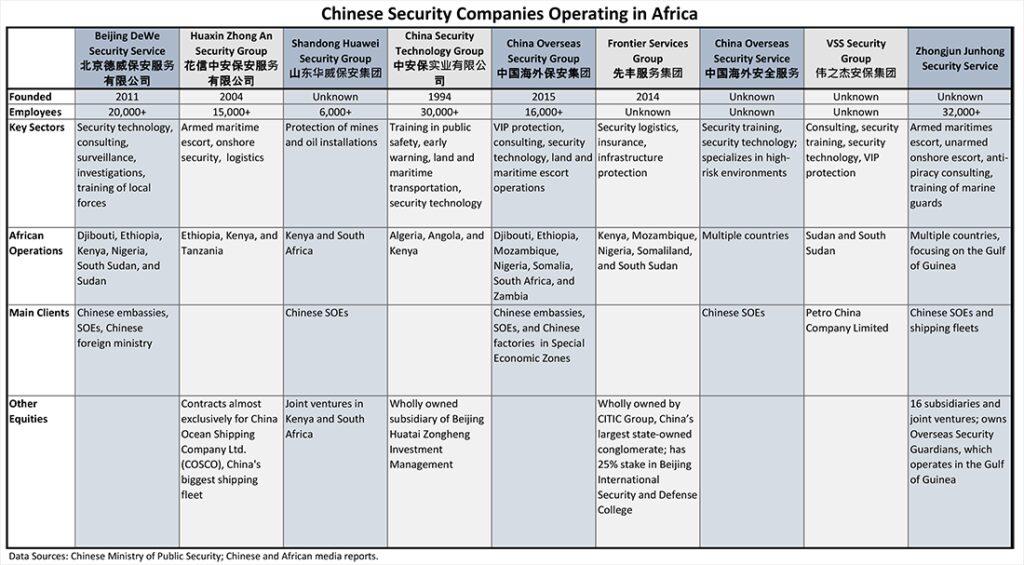

“A more robust regulatory process in Africa will be essential to prioritize and protect African citizen interests.”The Chinese government is, consequently, increasingly relying on Chinese security firms as part of its security mix. There are 5,000 security firms registered in China, employing 4.3 million ex-PLA and People’s Armed Police. Twenty of these are licensed to operate overseas and report that they employ 3,200 individual contractors, more than the size of PLA peacekeeping deployments, which number around 2,500 troops. The actual number of Chinese contractors in Africa is doubtlessly significantly higher. Beijing DeWe Security Service and Huaxin Zhong An Security Group employ 35,000 contractors in 50 African countries, South Asia, the Middle East, and China. Overseas Security Guardians and China Security Technology Group employ 62,000 in the same regions. In Kenya, DeWe employs around 2,000 security contractors to protect the $3.6-billion Mombasa-Nairobi-Naivasha Standard Gauge Railway alone.

China does not want its security providers to be compared to Russia’s shady Wagner Group or the disbanded American security firm, Blackwater. Yet that is a real danger. Moreover, Chinese security contracting comes with many of the same risks associated with some Chinese SOEs, including a lack of transparency, weak national controls, undue influence on regime elites, and social tensions.

The proliferation of foreign security firms has important policy implications for Africa as it undermines the government’s role as the primary security provider within a country and heightens the risk of human rights violations. A more robust regulatory process in Africa will be essential to prioritize and protect African citizen interests.

Security Contracting with Chinese Characteristics

The term “private security company” is misleading and inaccurate in the Chinese context. As a party state (dǎng guó, 黨國), China requires all “enterprises” to obey party directives, hence the catchphrase, “as the state advances, the private sector retreats” (guo jin, min tui, 国进民退).

A business with three or more employees must establish a ruling party organization within its structure. The chief executives of SOEs are not only trusted party members but also secretaries of their respective internal party organizations. Security firms must be state-owned sole proprietorships, or at least 51 percent of their capital must be state-owned.

In short, Chinese security firms are not private. They are controlled by the state and serve its interests. The opportunities they chase are lucrative, however. The Beijing-based China Overseas Security and Defense Research Center notes that Chinese SOEs spend about $10 billion annually on security globally. Their entry into Africa coincided with the PLA’s counterpiracy missions off the Somali coast dating back to 2008. Huaxin Zhong An and Overseas Security Guardians were the first to receive Chinese government authorization to provide armed maritime escorts to Chinese fleets in these waters.

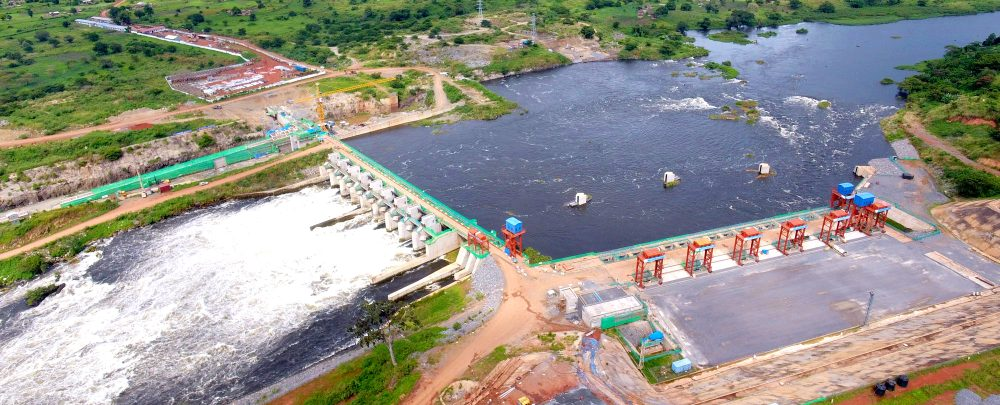

Chinese security firms have subsequently diversified their portfolios. Beijing DeWe Security Service is protecting a $4 billion natural gas project in Ethiopia for China’s Poly-GCL Petroleum Group Holdings. Shandong Haiwei Security Group protects Chinese-owned mines in Southern Africa. China Overseas Security Group, a conglomerate of five firms, protects Belt and Road projects in conflict zones, including Somalia. China Security and Technology Group secures land and maritime transportation routes, including the Gulfs of Guinea and Aden and the Lamu Port-South Sudan-Ethiopia Transport (LAPSSET) corridor.

Chinese security firms are not allowed to carry weapons domestically or overseas, requiring them to adjust their business models to suit different legal settings. The more permissive the environment, the greater latitude they have. In South Africa, where laws are strictly enforced, Chinese security firms work through local subsidiaries. For example, the Shandong Huawei Security Group operates a joint venture with Raid Private Security, which provides security for mining interests. In the more permissive setting of Kenya, Chinese security contractors are more hands on, working directly with local security forces to whom they provide supplementary pay, training, technical assets, intelligence, and equipment.

“Chinese security firms are not private. They are controlled by the state and serve its interests.”In the even more permissive settings of Sudan and South Sudan, Chinese security actors work with local forces in the field, and in some cases accompany them on missions. In 2012, ex-PLA units widely believed to be from VSS Security Group helped the Sudanese military rescue 29 kidnapped Chinese oil workers in South Kordofan province. In 2016, DeWe Security Service enlisted armed South Sudanese as backup to evacuate over 300 Chinese oil workers after fighting erupted between rival factions in South Sudan’s civil war. These ventures can compromise African citizens’ safety. China National Petroleum Corporation, for example, has secretly funneled fuel, hard currency, and armored personnel carriers to government militias to protect its South Sudan oil fields. Some of these South Sudanese forces have been accused by the UN of committing atrocities against civilians.

Some Chinese firms recruit veterans from Western militaries to form Western-managed but wholly owned Chinese outfits that are presumably more “professional.” The UK-based China Overseas Security Services styles itself as a Sino-British venture that “fully understands Chinese clients’ specific needs.” Even these “Western-looking” outfits, however, have courted controversy. The Hong Kong-based Frontier Services Group drew intense media scrutiny for questionable operations in numerous conflict-affected African nations, such as Somalia, South Sudan, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Frontier Services Group, with operations in a number of African countries, was founded and run by ex-U.S. Navy Seal and Blackwater founder, Erik Prince, and is wholly owned by CITIC Group, China’s largest state-owned conglomerate. In 2021, UN monitors accused Prince of using a “well-funded private military operation” to supply advanced weaponry, including drones and attack helicopters, to Khalifa Haftar, commander of a faction attempting to undermine the UN-backed unity government in Libya. Such examples serve as warning signs of the controversial dealings that can be anticipated between Chinese SOEs and foreign security firms eager to profit from China’s need for security contractors.

A Risk to Citizen Safety and Regulatory Integrity

China’s security contractors have caused their fair share of trouble in working around weapons restrictions. In 2018, two Chinese nationals were arrested in Livingstone, Zambia, for giving illegal military training to a local security company. The trainees wore uniforms similar to those used by the Zambia Wildlife Authority to avoid detection and blend in more easily in the popular tourist resort city. In neighboring Zimbabwe, two Chinese guards were imprisoned for shooting and injuring the son of a parliamentarian. They had been previously deported for firing on local workers during a pay dispute at a gold mine but stayed in the country illegally. In Kenya and Uganda, Chinese contractors were arrested in 2018 and 2019, respectively, for possessing military-grade gear for use by a local firm and an illegal communications interception system.

There is a perception that such misconduct often goes unpunished, even when cases go to court. In Zambia, two Chinese mine managers walked free after their attempted murder charge was dropped, sparking an outcry. They had shot and injured 11 coal miners during a dispute over working conditions. In countries with strong enforcement, Chinese SOEs have been compelled to adhere to stricter standards, such as observing local rules and regulations, using diplomatic channels to address safety concerns, and ensuring compliance with the International Code of Conduct Association (ICOCA) which sets guidelines for private security contractors.

The African Union’s Convention on the Elimination of Mercenaries is technically silent on foreign security firms, as it came into force in 1985 before foreign security actors became a common feature on the African security landscape. Civil society groups have been pushing African governments to update the convention given that foreign security and military contractors have become ubiquitous, particularly in unstable countries.

African agency is also growing, boosted by groups working on extractive industries, economic justice, and debt. These organizations have been creating awareness about the security dimensions of Chinese investments, including the use of security contractors. All this is aimed at bringing greater scrutiny and accountability to Chinese initiatives.

African Perspectives

The push for greater transparency and oversight of Chinese and foreign security firms in Africa has largely come from civil society actors. African civil society groups have focused a large part of their advocacy on extractive industries where Chinese SOE investments and security contracting are particularly visible. Strategic litigation has quickly emerged as a potent tool to create greater awareness and transparency around the opaque nature of security contracts. The Kenya Law Society, for example, challenged the legal basis of the agreement between Kenya and the China Roads and Bridges Corporation (CRBC) for the Standard Gauge Railway, which also covered the security contract with DeWe.

As a result, the CRBC project was declared illegal in June 2020 by the Court of Appeals of Kenya because it flouted procurement rules. A Chinese CRBC security manager, relatedly, was among those charged with fraud in an earlier related case. In Zimbabwe, litigation by the Zimbabwe Environmental Law Association (ZELA) led to a ban in September 2020 of all coal mining in Hwange National Park, which was being carried out by Chinese enterprises.

“Strategic litigation has quickly emerged as a potent tool to create greater awareness and transparency around the opaque nature of security contracts.”ZELA also launched an injunction compelling the government to furnish the public with status reports of the $3-billion Sengwa power plant currently being built by China Gezhouba Group, whose security is coordinated by the China Security Technology Group. Similar initiatives have been launched in other countries, including Ghana and Guinea. The litigants have understood that targeting large SOEs can be an effective means of bringing the activities of the security firms they hire to public attention.

There is an abiding suspicion of foreign security firms within African civil society organizations due to the involvement of foreign mercenaries in Africa’s deadliest civil wars. Hence, while China’s security firms are less visible than other external actors, they are viewed in a similarly negative light. Sentiments toward these firms are also shaped by public reactions to controversies surrounding the SOEs that hire them. Many protests against Chinese investments in Zambia, for example, center on long-running (and sometimes deadly) disputes between Chinese managers and local workers in the mining sector, which is dominated by Chinese SOEs. This is also the case in Zimbabwe.

Looking over the Horizon

Given the current trajectory, the presence of Chinese security firms in Africa can be expected to grow over the next decade. These firms will likely draw greater scrutiny given that popular demand for more accountability of Chinese SOEs—which hold the purse for security contractors—is also growing. Strategic litigators understand that calling for increased transparency around Chinese SOEs will also bring the activities of Chinese security contractors to light. African reformers also understand that China is sensitive to its image, especially since its investment in Africa is largely welcomed. It is also in China’s self-interest to enforce standards on its SOEs and security contractors or risk damaging its soft power influence around Africa.

Yet, ordinary Africans are also increasingly likely to see the negatives of China’s expanding footprint, especially when controversial SOE investments and questionable activities by Chinese security firms make the news. While largely remaining silent on the expansion of Chinese security firms on the continent, African governments can ill afford to ignore the sentiments triggered by these firms. From a national security perspective, African governments and the African Union need to assess the role and sustainability of foreign security firms within Africa’s security architecture. Given their rate of growth, the issue of foreign security firms in Africa will not fade away anytime soon. This raises fundamental questions over the oversight, role, and capacity of African security sectors to safeguard African interests—and foreign investments—on the continent.